Crypto boom strains Kazakhstan’s coal-powered energy grid

Kazakhstan is struggling to meet the energy needs of its booming cryptocurrency mining industry, which is flourishing thanks to cheap power and an exodus of crypto miners from neighbouring China.

The Central Asian nation of 19 million has become the world’s second-biggest bitcoin mining location after the United States in recent months, according to the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

Now the government is trying to decide how to tax and regulate the largely underground and foreign-owned industry, which has forced the former Soviet republic to import power and ration domestic supplies.

Moreover, local mining farms are mostly powered by ageing coal plants which themselves, along with coal mines and whole towns built around them, are a headache for authorities as they seek to decarbonise the economy.

While some people see crypto as the way to a quick fortune, many governments fear that privately operated highly volatile digital currencies could undermine their control of monetary systems, promote financial crime and hurt investors. China last month banned all crypto transactions and mining.

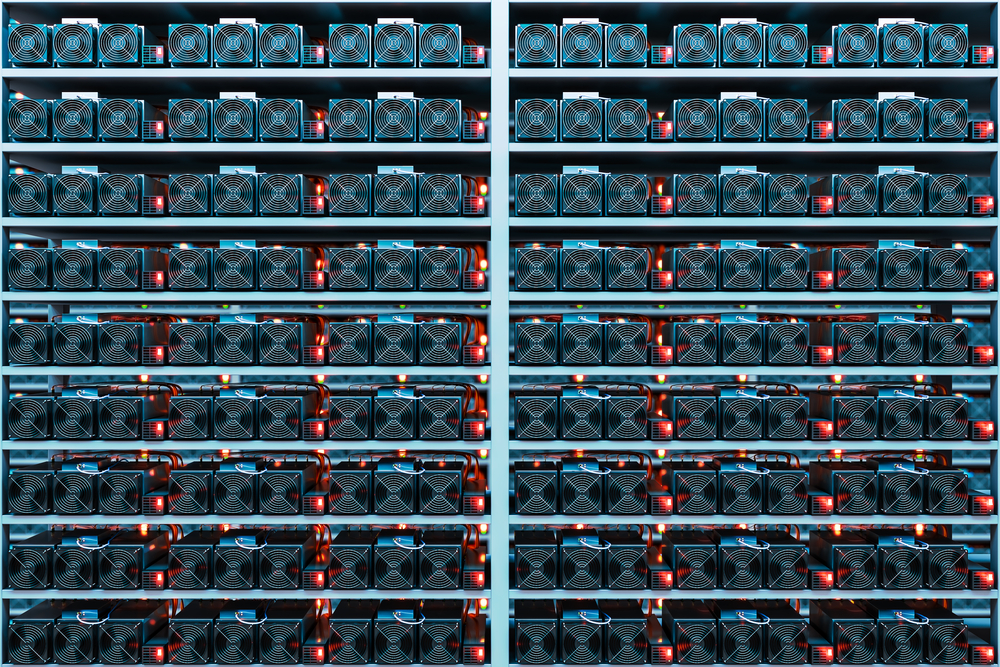

Crypto mining, the energy-intensive computing process through which bitcoin and other tokens are created, is seen by many as hurting global environmental goals.

Crackdown imminent

The Kazakh government plans to crack down first on unregistered “grey” miners who it estimates might be consuming twice as much power as the “white” or officially registered ones.

“I think we will have the directive (limiting power to unregistered miners) issued before the end of this year, because this issue cannot be delayed any longer,” Deputy Energy Minister Murat Zhurebekov said this month.

He did not explain how authorities planned to locate “grey” miners, whose farms are often hidden in basements or abandoned factories. But sources say their heat signatures could be detected by satellites.

The ministry says “grey” mining may be consuming up to 1.2 GWt of power, which together with “white” miners’ 600 MWt comes up to about 8% of Kazakhstan’s total generation capacity.

Some “grey” miners say they are considering going “white”, but are unsure about how heavily they may be taxed. Tax code amendments passed in June provide for a tax of 1 tenge ($0.0023) per kilowatt-hour, but there are also proposals to make miners pay more for energy.

“The tax that the government plans to introduce is something that miners can afford to pay,” said one “grey” miner who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But it is unclear what demands the government may put up further on.”

Environmental cost

The root of the problem lies in Kazakhstan’s state-regulated and artificially low electricity prices, which the government may not want to increase while struggling to contain inflation.

“A price reform is definitely necessary,” says Eric Livny, regional economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

“What we have in Kazakhstan is heavy reliance on coal with very low prices … But this creates very big problems in meeting the obligations that Kazakhstan has taken on with regards to making the economy greener.”

Kazakhstan has one of the world’s biggest coal mines, Bogatyr, and the nearby town of Ekibastuz has developed around the coal industry.

Some crypto miners say the government could let their industry offset taxes with investments in renewable energy.

“Kazakhstan has an opportunity to develop its weak electric power sector at others’ expense and make some money on top of it,” says Yedige Davletgaliyev, an engineer at Blockchair.com, a blockchain analytics company.

(By Mariya Gordeyeva and Olzhas Auyezov; Editing by Giles Elgood)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments