Covid, debt and precious metals

Precious metals are loving the uncertainty the coronavirus has created.

Despite limited successes some countries have had with reopening, the virus is nowhere near contained. As of this writing, close to 6 million worldwide are infected and 365,328 have died. The important columns in the table below from the heavily visited Worldometer’s coronavirus page, are the yellow and red.

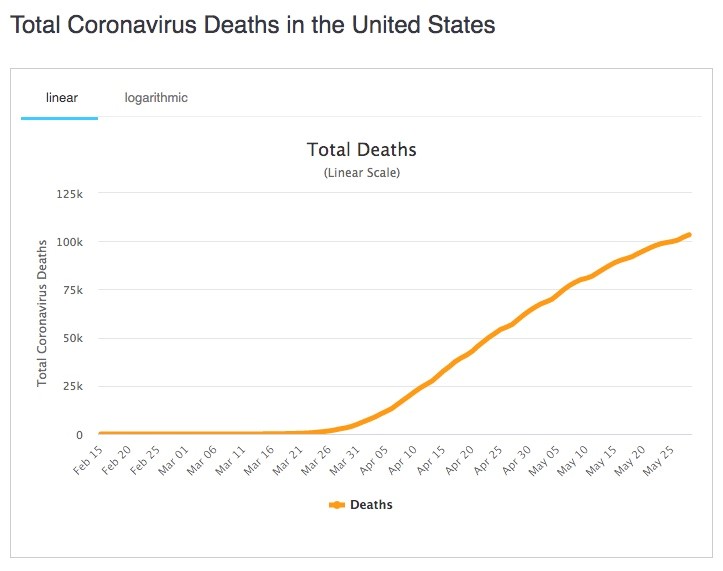

The United States is by far the world “leader” in covid-19 cases and deaths, a respective 1,787,262 and 104,308. That is more than triple the next-worst-hit country, Brazil.

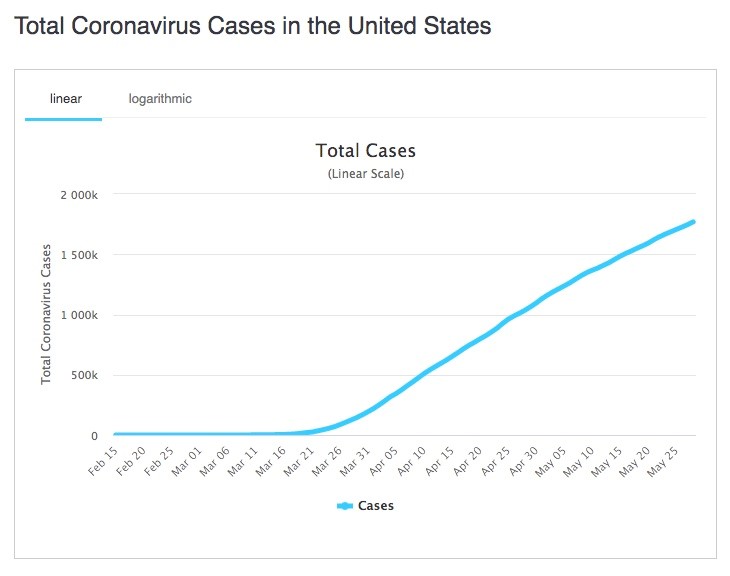

Despite roughly 1,800 deaths per day and rising infection rates, at least 41 US states are easing restrictions or planning to do so. The fact is, reopening plans are failing to meet key benchmarks established by public health officials. This has prompted the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to throw previous forecasts of the virus’s toll out the window. Its new prediction has 3,000 Americans dying daily by June 1 – a 9/11 every day. Do the graphs below look to you like a flattening curve?

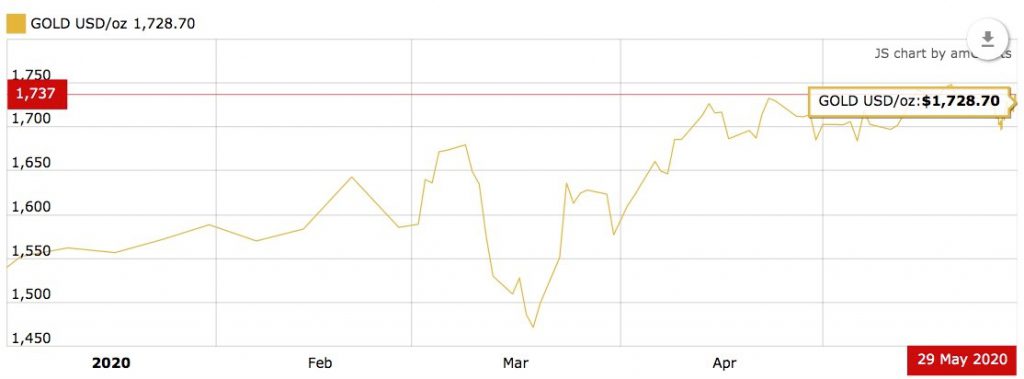

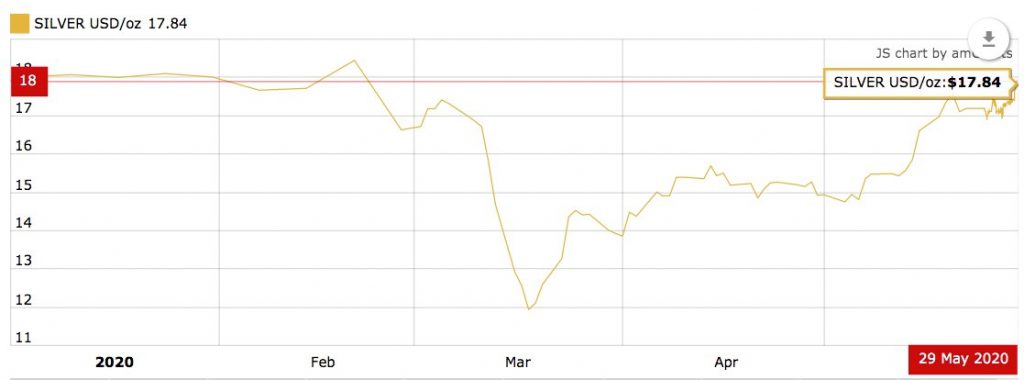

Gold and silver have been the main beneficiaries of the global pandemic.

Spot gold gained $10 an ounce on both Thursday and Friday, finishing the week at $1,728 in New York. Gold futures for August delivery were even higher, rising $15 to settle at $1,743/oz. Since dipping sharply in mid-March, gold has soared $257, or 17%.

The really big performer though is silver. Since taking a dive in March to $11.94/oz, spot silver has risen nearly $6.00, for a gain of 47%! The “poor man’s gold” made a 50-cent move Friday, hitting $17.84 in New York.

In this article we return to one of our current favorite topics, how precious metals are likely to perform during what looks increasingly like a prolonged war against covid-19, specifically the impact of out-of-control debt levels many countries are being forced to incur, as their economies are ravaged by the new and scarily unpredictable respiratory illness.

The return of covid

From the very beginnings of the crisis, health officials have warned of the potential for a resurgence. Historically, it is common for these types of viruses to re-infect populations. Often the second round is worse than the first. According to health experts, the fact that covid-19 is so deeply entrenched in the world population, means it is unlikely to be eradicated, like SARS was in 2003, and instead is likely to return regularly, like seasonal influenza.

Indeed, after a few weeks of experimental lifting of social restrictions, we are seeing boomerang-like returns of coronavirus cases in a number of countries. The most surprising are China and South Korea, early victims in the crisis whose strong lockdown measures and testing protocols appeared to nip covid in the bud.

This week, South Korea saw three straight days of rising infections, with 79 new cases reported Thursday, the most since April 5.

Earlier this month, Korea’s success at containing the virus was threatened by hundreds of party goers who descended upon a neighborhood popular with young South Koreans and foreigners. The country rescinded a go-ahead for bars and clubs to re-open after a spike in cases, prompting a warning from President Moon Jae-in to “brace for the pandemic’s second wave” said the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Earlier in the year, when coronavirus cases in China peaked, Beijing locked down millions of people in Hubei province, including the 11 million inhabitants in the virus epicenter city of Wuhan.

On May 12, a month after the lockdown was lifted, Wuhan saw a cluster of new cases, followed by 34 cases and one death reported in the northeastern province of Jilan.

Fresh covid-19 cases have also appeared in Germany, Iran and Lebanon. In France, a partial reopening on May 11 has backfired, with more than 3,000 new daily infections reported.

One of the most concerning developments is the spread of the pathogen in Russia; on May 14, 232 new deaths were reported in 24 hours. The sprawling country now has the third most cases in the world, although surprisingly few deaths, at 4,374 versus Canada’s 6,979. Many however question the accuracy of Russia’s low death count, suspecting under-reporting by government officials.

India has had one of the world’s strictest lockdowns since March 24, but it has only slowed the spread of the virus, not flattened the curve in the country of 1.3 billion. Recently The Guardian reported the virus beginning to overwhelm the teeming metropolis of Mumbai.

Nearly a quarter of India’s covid-19 deaths are in the state of Maharashtra, and the city of 20 million has emerged as the center of the outbreak. According to health officials, the peak began on May 6 but shows no signs of flattening, with cases still doubling every week.

Another scary scenario is the coronavirus hitting Africa, where countries lack adequate sanitation and medical facilities. Millions of Africans are poor and living in slums, where cramped conditions prevent social distancing and where the virus could spread like wildfire. On Friday Global News reported As cases steadily rise across Africa, too, officials who are losing the global race for equipment and drugs are scrambling for homegrown solutions.

US reopening fail

The Trump administration has been widely criticized for the manner in which it has handled the pandemic – an “epic fail” in today’s youth parlance.

At first Trump downplayed the seriousness of the virus, then quibbled with governors over whose responsibility it was to provide personal protective equipment and life-saving ventilators – preferring to pick on Democratic governors thus shamefully politicizing a state of emergency – one he did not officially declare until mid-March, 8 weeks after the first case appeared in Washington State.

After two months of lockdowns the White House released a set of re-opening guidelines, which include that states show a “downward trajectory” of cases. As of May 7, over half of US states had begun to reopen their economies, but most failed the federal criteria recommended for resuming business and social activities. In over 50% of the states easing restrictions, The New York Times reported, case counts are trending upwards, positive tests are rising, or both.

Time Magazine writes an interesting narrative comparing the way the US has handled containment and tried to reopen, versus other countries that have done both more successfully. The common elements appear to be: test early and as many as possible (duh), do contact tracing to identify virus clusters and locations; maintain social distancing; and impose strict lockdowns, no half-measures.

Countries that haven’t loosened too much, too fast have done much better in preventing the virus from making a second appearance. Here are the key takeaways from Time:

Countries that acted more quickly to curb the spread of the virus have limited the damage on both fronts. In the early days of their fight against COVID-19, New Zealand, Norway and Switzerland tested their populations at nearly 40 times the U.S. rate, per capita, and now have one-fifth the death rate.

Having failed in its initial response, the U.S. now risks risks making matters worse… In many cases, governors are plunging ahead with reopening despite failing to meet key benchmarks established by public-health officials.

To avoid these shocking death rates, Americans should look at what has worked elsewhere. Industrialized nations in Europe and Asia have begun opening up their economies by relying on continued social distancing, widespread testing, and a network of contact tracing to identify and contain new outbreaks. South Korea built an innovative digital infrastructure to identify and track every new coronavirus case within its borders. Germany set the standard for preventative testing and an incremental, staged plan for reopening.

So, if the way forward is clear, can the U.S. simply copy what’s working elsewhere? The straightforward answer is no. Unlike in places like South Korea, there’s no national reopening plan in the U.S. Instead, 50 governors are charting their own paths. The White House and the CDC have released bare-bones guidance for reopening, but neither entity can dictate what states do; they can only hope that governors choose the right course.

As of early May, that wasn’t happening. More than a dozen governors’ reopening plans appeared to either outright ignore, or interpret very loosely, the Trump Administration’s nonbinding reopening guidelines, according to an Associated Press analysis. At least 17 states that are in the process of reopening, including Georgia, California, Florida, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Texas, failed to meet the White House’s key metric for reopening: a downward trajectory of new cases or positive test rates for at least 14 days.

As US re-openings fail, the virus will make a comeback. There is always about a 10-day lag in the reporting of new cases. We should begin to see the first data this week or next. Expect the curve in the US to keep going up and up.

Meanwhile the economic statistics that keep rolling in paint a darkening picture. Despite the gradual reopening of businesses throughout the country, last week 2.1 million Americans were thrown out of work, bringing to 41 million the number who have joined the ranks of the unemployed since covid-19 took hold in mid-March.

In April US unemployment shot up to 14.7%, the highest since the Great Depression. Economists expect it will be near 20% in May.

“That is the kind of economic destruction you cannot quickly put back in the bottle,” Adam Ozimek, chief economist at Upwork, was quoted in the Associated Press.

Covid and debt

The US government and policymakers around the world have no choice but to unfurl massive stimulus programs to help their citizenries to deal with what is already known to be the worst recession since World War II, and what many believe is heading for a depression.

Governments that don’t have the funds to pay for these programs have two choices: print money or borrow it. Money-printing is inflationary, so most choose to borrow, especially with interest rates at record lows.

As of May 15, the Economic Times of India reported central banks and governments worldwide had unleashed $15 trillion of stimulus, via bond-buying and spending.

The Globe and Mail in April made an interesting point:

In fact, the urgent question isn’t whether these countries can afford to take on more debt. It’s whether they’re taking on enough debt to fund the stimulus programs necessary to avert an even deeper downturn.

Analysts at Bank of America describe the massive US$2-trillion stimulus package passed by U.S. Congress in March as the “bare minimum.” Scott Minerd, chief investment officer at Guggenheim Partners, told Reuters he expects more support will be needed for the U.S. economy. If so, Canada is likely to be caught short as well.

Currently there is an additional $3 trillion tied up in the US Senate, the new package of stimulus measures having originated in and passed by the Democrat-led House of Representatives. The Republicans control the Senate.

The Globe continues,

Without relief, many households will go bust. Their incomes will shrink or vanish, and they will default on mortgages, rent payments and car bills. Meanwhile, many restaurants, retail stores, travel operators, malls, hotels and airlines will tumble into bankruptcy. With all those employers gone, many workers will not have jobs to go back to when the virus does come under control. The slump could stretch on for years and turn into a full-on depression.

This week the Centre for Risk Studies at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School determined that the global economy faces an “optimistic loss” of $3.3 trillion in the case of a rapid recovery, and $82 trillion in the event of a depression. The consensus projection is a loss of $26.8 trillion, or 5.3% of global GDP, in the coming five years.

For governments, one of the biggest worries of the pandemic extending beyond a few months, is the fall in tax revenue, with so many people out of work and businesses closed.

Earlier this week, the Financial Times quoted the OECD saying that sharp drops in tax revenues are expected to dwarf the stimulus measures. Average government liabilities are anticipated to rise from 109% of gross domestic product to 137%, placing public debt burdens on countries at the current level of Italy, or a $13,000 debt per person.

According to the World Bank, countries whose debt-to-GDP ratios are above 77% for long periods experience significant slowdowns in economic growth. Every percentage point above 77% knocks 1.7% off GDP, according to the study, via Investopedia. The United States’ current debt-to-GDP ratio is 106.5%.

In fact debt levels across the world’s richest economies were becoming unsustainable long before the coronavirus washed up on their shores.

In 2019 the global debt to GDP ratio hit an all-time record of 322%. Over the last 13 years, debt has increased by $128 trillion, but GDP has only risen by $27 trillion. Ie. countries borrowed five times more than their economies managed to produce. Finland, Canada and Japan saw the largest increase in debt-to-GDP ratios of all the countries tracked in a one-year period.

The Institute of International Finance in January predicted that total global debt will exceed $257 trillion in 2020, and that was before the coronavirus.

Prior to covid-19, the federal deficit for the current fiscal year was expected to be $1.1 trillion. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), this has been tripled to $3.7 trillion – which is more than the total federal debt President Clinton incurred while he was in office, and much higher than the $1.4 trillion deficit during the 2007 financial crisis.

In November, total US debt surpassed $23 trillion for the first time. Adding the projected budget shortfall to the existing debt means the national debt will rise to $26.9 trillion by September 30, 2020. And this is assuming no additional stimulus is needed, which is highly unlikely. Remember, the US Senate is poised to sign off on an economic stimulus plan worth $3 trillion.

We already know that when government debt reaches a certain threshold – according to the Bank for International Settlements it’s 85% of GDP – economic growth is impeded.

Forbes does a nice job of explaining why the ballooning US federal debt is such a big deal:

Any debt incurred today must be repaid using future revenue, which reduces the amount of money available in the future for investment, spending, and saving. As more debt is incurred, larger payments are required to service it. A CBO paper from 2014 entitled, CBO: Consequences of a Growing National Debt, lists four main problems a country will encounter if it accumulates too much debt. Excessive debt will lead to:

1. Lower national savings and income

2. Higher interest payments, leading to large tax hikes and spending cuts

3. Decreased ability to respond to problems

4. Greater risk of a fiscal crisis

With respect to number four (in sync with the BIS paper), the CBO said,

“All else being equal, the larger a government’s debt, the greater the risk of a fiscal crisis.”

Yes, the federal debt is about to mushroom. Since all debt must be repaid, the federal government will be forced to extract more and more dollars from the economy to service it, leaving less for spending, investing, and saving. This will lead to slower economic growth as the private sector struggles to fund public sector spending.

Gold and debt to GDP

In a previous article we discussed the close relationship between gold and the debt to GDP ratio.

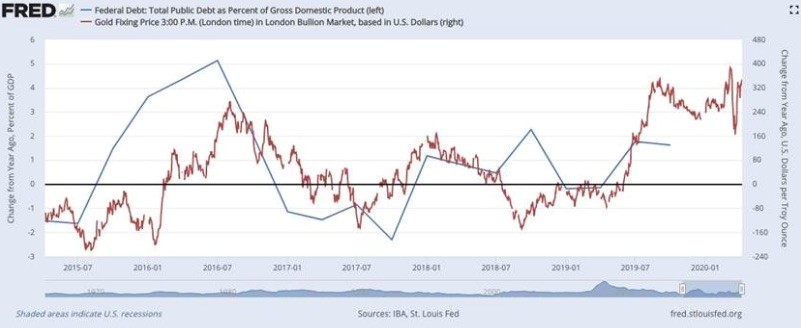

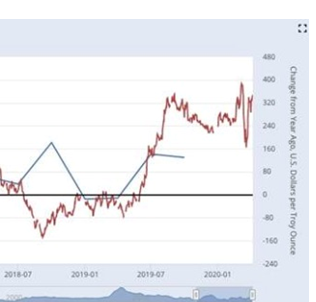

Historically, we know that as the percentage of debt to GDP rises, so does gold. For a reminder of how this works, look at the FRED chart below.

Moribund for five years, as the commodities boom of the late 2000s ran out of gas and led to a bear market for most metals, we see the gold price coming back to life in 2016 when it rose above $1,300 and has kept going to its current ~$1,700 an ounce. This corresponds to rising debt and falling GDP.

This week, the Commerce Department reported gross domestic product, the broadest measure of economic health, fell 5% in the first quarter, an even bigger decline than the 4.8% estimated a month ago. The Atlanta Fed projects economic growth during the second quarter to contract 41.9%!

That is the GDP side of the equation. On the debt side, covid crisis emergency stimulus measures include at a minimum, $2 trillion in new spending, and possibly doubling the Fed’s balance sheet to $10 trillion. As of May 20, the Federal Reserve balance sheet was at a record $7.09 trillion.

The longer stimulus measures continue, and GDP falls, along with a creeping expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet and negative real interest rates (interest rates minus inflation) which are always bullish for gold, we see no reason to doubt that gold will keep climbing.

Consider what a $10 trillion Fed balance sheet will do to the debt-to-GDP ratio. Already at 106.5%, a level not seen since World War II, it’s not inconceivable for the ratio to spike to $150%, or 200%. That would mean for every dollar the US economy produces, it has to borrow $1.50, or $2.00. That’s insane.

Now think about what this could mean for gold.

Returning to the St Louis Fed chart, gold’s red line showing volatility at the far right side, reflected in the stock market convulsions in February-March, could very well begin a steadily upward trend, similar to what happened in 2008-11, possibly even testing the $1,900 highs reached in September 2011.

It seems that unsustainably high debt is baked into the cake, as far as gold prices go. In the current environment, without a change in the weather, so to speak, regarding the coronavirus, governments simply have no choice but to keep spending, taking on more debt, as economic growth continues to falter.

We believe the only way out is a “Debt Jubilee” that retires all of the massive accumulation of global debt.

This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. A reading of history shows that retiring debt can actually make a country’s economy, and its indebted citizenry, all the better for it, as we explained in our ‘Debt Jubilee’ article.

Because we live in a fiat monetary system, currencies are not backed by anything physical; the reserve currency, the US dollar, was de-coupled from the gold standard in the early 1970s. It’s not like a raid on vaults full of gold, which have an inherent, physical store of value.

In reality there is nothing preventing central bankers from doing a complete global reset, putting all debt back to zero.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments