Could global energy use go up while per capita emissions go down?

It’s harder to think about the future of today’s global energy system than it used to be. War, inflation, supply chain pressures, trade friction: The present is, so to speak, much more present than in years past.

But I was asked to talk about it at a conference this week, and my strategy was to start with the long term, since we have centuries of energy consumption data and millennia of climate data. I focused on two trends in particular: total primary energy consumption since the middle of the 20th century and greenhouse gas emissions since the middle of the 18th century. Today these data show a meaningful break in where energy is consumed, and an important inflection point — hopefully a durable one — in global emissions.

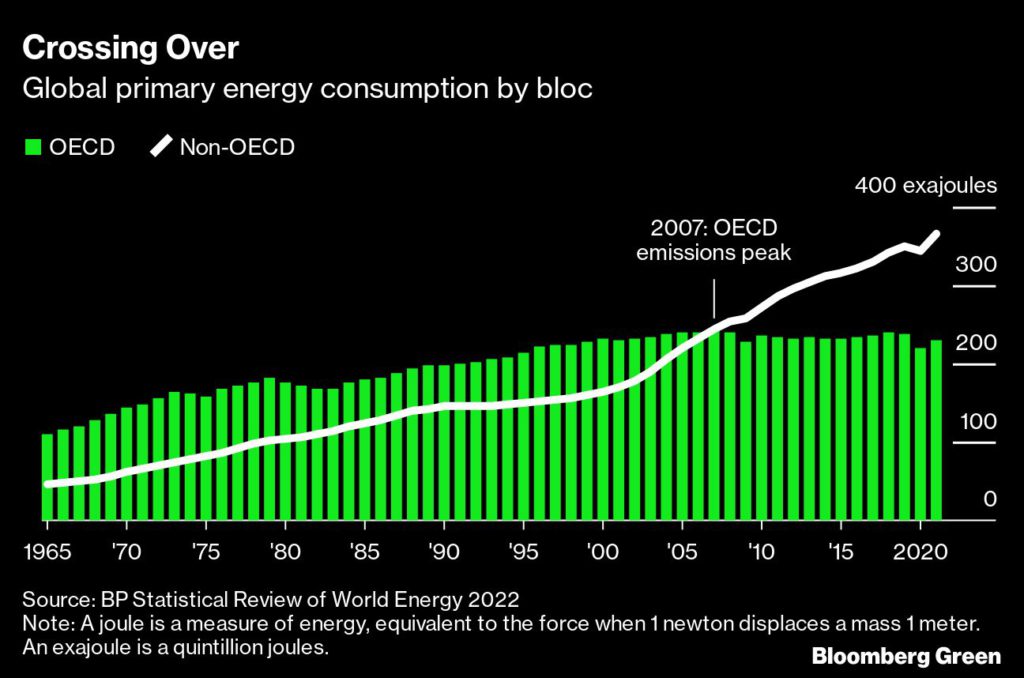

The first trend is the most important. We can study it using data from oil supermajor BP Plc, which keeps statistics on primary energy consumption back to 1965. Sort them by economic bloc — the mostly Western and wealthy countries of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) in one group, and all others in another — and it becomes clear: Rich country emissions peaked 15 years ago and have declined since.

In 1965, the OECD comprised more than 70% of global emissions. Today, non-OECD countries account for more than 60%. These countries also make up the entirety of growth in emissions. Also notable is that OECD emissions peaked in 2007, the year before the global financial crisis, which is also the same year that non-OECD consumption surpassed it.

OECD energy consumption is very clearly tied to global economic activity and to economic and resource shocks. We can clearly see the impact of the two oil price shocks of the 1970s, the financial crisis and Covid-19. Non-OECD consumption, on the other hand, is far smoother, with only Covid-19 showing up as a meaningful, if brief, disruption to a pattern of increasing consumption.

Look closer at the non-OECD line and we can see that primary energy consumption begins to accelerate meaningfully in 2001. It is no coincidence that was the year of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization , and with it an extraordinary increase in economic output. That is not to say that increases in India and Southeast Asia are inconsequential, but China’s is particularly meaningful.

To put it another way: Since the year that China joined the WTO, non-OECD primary energy consumption has more than doubled. In that same time, OECD consumption has declined ever so slightly. A continuing decline in OECD consumption is probably likely, given ambitious clean energy and electric transport targets. Outside the OECD, primary energy consumption will almost certainly keep growing, making aggressive deployment of more efficient processes and renewable power all the more important.

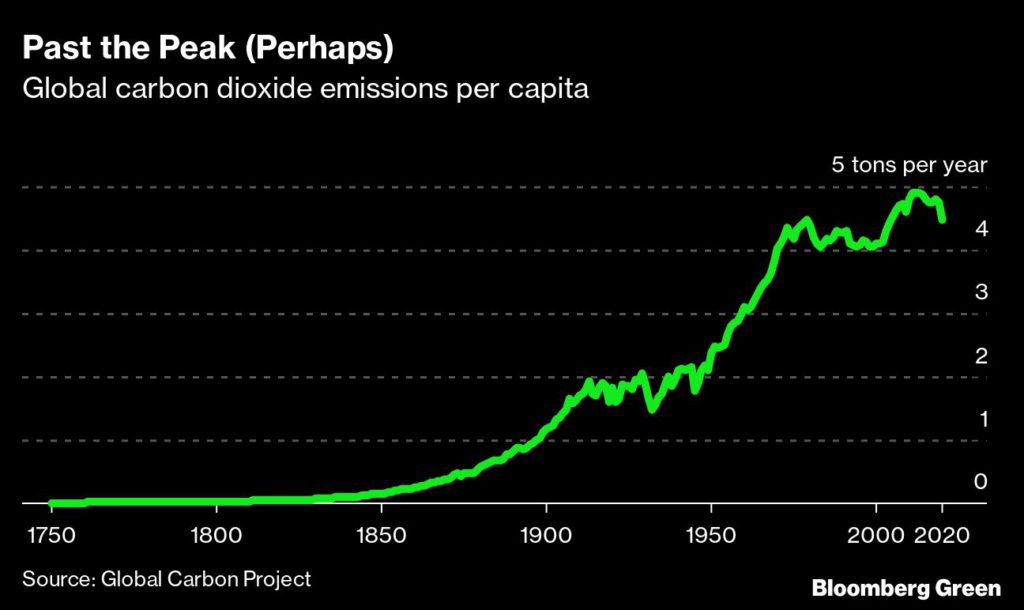

The second trend worth exploring is per-capita emissions from fossil fuel combustion. The Global Carbon Project publishes per-capita emissions data since 1750, which makes for a rather dramatic chart. Two and a half centuries ago, per capita emissions were about 115 kilograms of CO2 per year. In 2020, that had risen to 4.46 tons: a 385-fold increase.

However, per capita emissions in 2020 were down 9% from their peak eight years earlier. The only other decline that significant in the past five decades was after the second oil crisis, from 1979 to 1983. Prior to that, similar drops came at the beginning of World War I; during a UK miners’ strike in the early 1920s; in the Great Depression; and at the end of World War II.

Those significant 20th-century drops also corresponded with declines in primary energy consumption. From 2012 to 2019, however, primary energy consumption rose 11% while per capita emissions fell. After Covid, the 2021 rebound in coal, gas and oil consumption was massive, leading to the biggest one-year increase in primary energy on record. At the same time, renewable energy’s contribution also grew significantly, increasing its share of the total by more than half a percent from 2020 to 2021.

Would I call it a decoupling? Not quite yet. But it is an important break in the longstanding relationship between primary energy consumption and emissions. That relationship offers many levers to pull in the future. We should use them to create a growing global economy, one that consumes energy more efficiently and benefits from a vast expansion of clean energy requiring no fuel. That will reduce fossil fuel combustion and the associated emissions while improving the lives of a larger world population.

(By Nathaniel Bullard)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments