Copper trapped between faltering supply and weak demand

It’s turning out to be a bad year for copper supply.

Both mined and refined production fell in the first half of the year, according to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG). What was always going to be a year of weak supply growth has been made worse by a stream of supply disruptions.

At other times such production woes would have been a red flag for copper bulls, who like nothing more than trading copper’s notoriously volatile supply side.

This year, however, falling production is doing no more than preventing the copper price falling further.

At $5,665 per tonne London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month copper is a long way off April’s highs above $6,600 and is now down by 3% on the start of January.

The problem is that copper demand is faring just as badly as supply, with manufacturing activity contracting just about everywhere.

Supply hits

World mine production fell by around 1.4% in the first half of 2019, according to the ICSG’s latest monthly statistical bulletin.

Concentrates output declined by 1%, while straight-to-metal SX-EW (solvent-extraction-electrowinning) mines produced 3.5% less than last year.

Some of this was expected, such as the 55% decline in Indonesian production, where both the Grasberg and Batu Hijau mines are transitioning between ore bodies.

However, unexpected supply disruptions have also been accumulating.

Analysts at JP Morgan have slashed almost 839,000 tonnes from their production forecasts due to weather disruption in Chile, strikes in Peru and lower output in the African Copperbelt, “where a host of fiscal and legislative issues have crippled production”. (“Metals Quarterly”, Sept. 23, 2019).

Analysts at JP Morgan have slashed almost 839,000 tonnes from their production forecasts due to weather disruption in Chile, strikes in Peru and lower output in the African Copperbelt

The downward revisions equate to 3.7% of the bank’s initial production expectations and 74% of its forecast disruption allowance for 2019. The rate of disruption is running at levels not seen since 2012.

Disruption at the refined metal stage of the supply chain is even worse. World refined production dropped by 1% in the first half of 2019, according to the ICSG, with a 1.5% decline in primary output offset by a slight lift in secondary (from scrap) production.

The ICSG’s May forecast for a 2.8% increase in production has been undone by problems in Chile (technical), India (the continued suspension of the Tuticorin smelter) and Zambia (power interruptions, smelter outages and a new tax on imported raw materials).

Other things being equal, such a litany of supply woes would mean a higher copper price.

Not this year, though.

Demand weakness

The problem is that demand is weakening almost as fast as production.

The ICSG, which was forecasting in May a 2% increase in global apparent usage this year, estimates that usage actually fell by 1% in the first half of the year.

Even that assessment may be on the rosy side given the problems calculating usage in China, the world’s largest consumer.

Apparent usage in China was up by 3% in the first six months of 2019, according to the ICSG. But bank analysts are sceptical. Both JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley are looking for Chinese demand to rise by just 1.5% this year, while Goldman Sachs is anticipating even weaker 0.5% growth.

The problems are multiple, ranging from weakness in the automotive sector to lower-than-expected investment in the power grid and the much-discussed gap between new housing starts (positive for steel) and completions (positive for copper).

Outside of China the copper demand picture is even worse, the ICSG calculating a 3% decline in the first half of the year.

The continuing trade tensions between the United States and China dominate the headlines but there are other negatives at work such as the trade stand-off between South Korea and Japan, both major manufacturing hubs.

Europe is a particular point of underperformance.

Goldman Sachs estimates regional output of semi-manufactured copper products is running 12% below last year’s levels. This is down to “overlooked” headwinds such as Brexit, Italian political uncertainty and Turkish currency instability. (“Copper demand pick-up delayed, but not derailed”, Sept. 27, 2019).

Tipping the balance

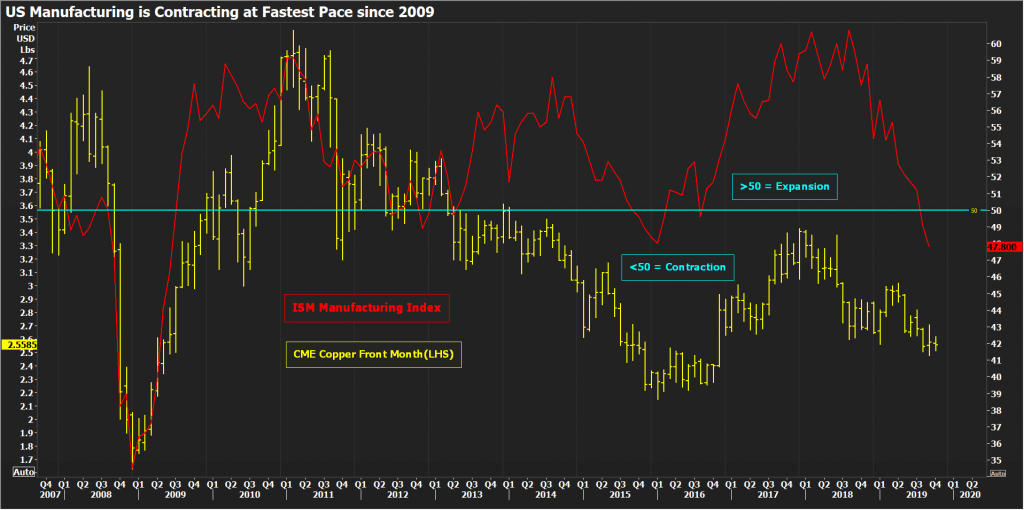

The United States was the previous stand-out in terms of manufacturing activity.

However, even here the outlook is rapidly darkening, given the sharp drop in the Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) purchasing managers index (PMI).

The index slumped to 47.8 last month, below the 50 mark which denotes expansion or contraction and the weakest reading since the recession of 2009.

JP Morgan has just cut its 2020 average price forecast from $5,400 to $5,050 next year

This means, to quote BMO Capital Markets, that over two-thirds of global PMI readings are now either in negative or at best neutral territory, suggesting a cold recessionary wind is blowing through the global manufacturing sector.

Moreover, delve beneath the headline readings and it becomes clear that new orders are falling even faster, implying things are going to get worse before they get better.

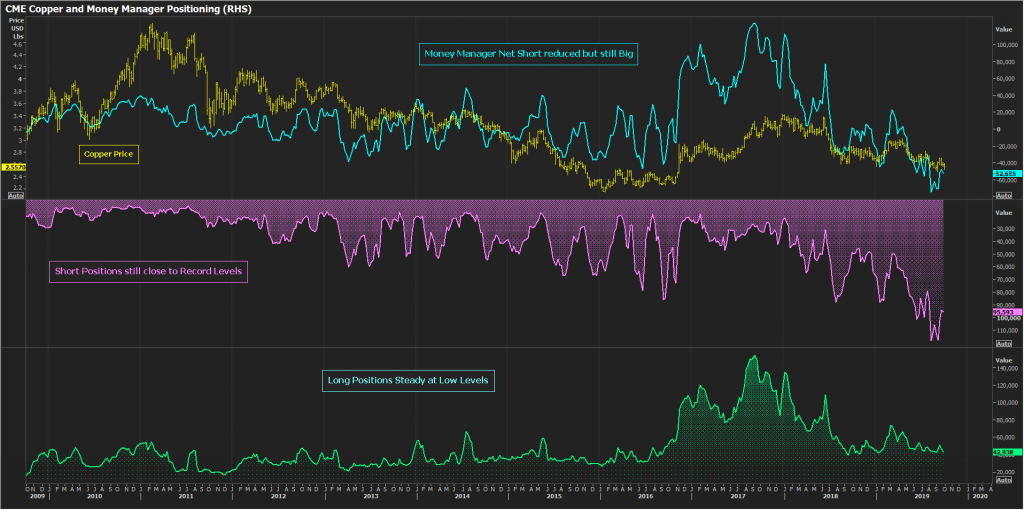

This is why funds are still holding a mega short position on “Doctor Copper” on the CME exchange. The collective bear stance has retreated slightly to a net 52,655 contracts from an August peak of 74,597, but by any historical yardstick this is still a big short bet.

Against such a backdrop, copper’s supply woes are sufficiently acute to prevent a demand-led price meltdown.

Bulls can take heart from the fact that the physical market is not being overwhelmed by surplus metal. Global exchange stocks of copper ended September at 413,000 tonnes, up 62,000 tonnes on the start of 2019 but down by 56,000 tonnes on August 2018.

The market feels just about balanced, although as ever with copper there is no clear consensus as to whether that balance leans to the side of supply surplus or supply deficit.

The ICSG calculates a deficit of around 220,000 tonnes in the first half of the year but this is a marginal call in a 24-million-tonne-plus global market.

Nor is there any clear consensus as to what happens next. Goldman Sachs is remaining medium-term bullish with a 6-month call on copper at $6,500 per tonne.

JP Morgan has just cut its 2020 average price forecast from $5,400 to $5,050 next year.

The difference in views is all about the demand outlook. Goldman is expecting a bounce, JP Morgan a further deterioration, particularly in China.

Copper’s supply instability is a “known known”. Right now, though, it’s copper demand that is the big “known unknown”.

(By Andy Home; Editing by Louise Heavens)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments