Copper-gold deposits to help gold miners overcome depletion dilemma

Every fiscal quarter the World Gold Council puts out a wonderful little report on the gold market, that is made into an article by just about every mining news outlet. For reasons unknowable to mere mortals like us, the report focuses on gold demand. The reader has to go deep into the report to find the other half of the story, gold supply, and in particular, mined gold supply.

Doing so in the WGC’s latest instalment, the full-year 2019 gold market report, reveals some startling conclusions about “peak gold”.

The concept of peak gold should be familiar to most readers, and gold investors. Like peak oil, it refers to the point when gold production is no longer growing, as it has been, by 1.8% a year, for over 100 years. It reaches a peak, then declines.

While gold production has been increasing every year, it’s been growing in smaller and smaller amounts. That is, while gold output in 2018 was higher than 2017, it was only 1% higher – 3,347 vs 3,318 tonnes, according to the World Gold Council. Production in 2017 was 1.3% more than 2016.

This is itself does not disprove peak gold, nor does the WGC’s total gold supply figures which include mine production, recycled gold and net producer hedging, which contributes to overall supply.

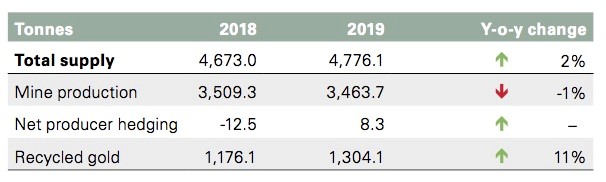

According to the report, in 2019 gold demand reached 4,355 tonnes, against 4,776 tonnes of supply. Mined gold production was 3,463 tonnes, jewelry recycling hit 1,304 tonnes, and 8.3 tonnes were hedged.

If we stop there, we show a slight gold supply surplus of 421 tonnes. Peak gold debunked!

Not so fast, let’s think about those numbers for a minute. In calculating the true picture of gold demand versus supply, we, at Ahead of the Herd don’t, and won’t, count jewelry recycling. What we want to know, and all we really care about, is whether the annual mined supply of gold meets annual demand for gold. It doesn’t! When we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, we get an entirely different result. ie. 4,355 tonnes of demand minus 3,463 tonnes of production leaves a deficit of 892 tonnes.

This is significant, because it’s saying even though major gold miners are high-grading their reserves – mining all the best gold and leaving the rest – even hitting record gold production in 2018, they still didn’t manage to satisfy global demand for the precious metal, not even close. Only by recycling 1,304 tonnes of gold jewelry could gold demand be satisfied.

Gold recycling includes people selling their jewelry when they think they can get a good price for it. Recall that the gold price started its rally in June, after the US Federal Reserve decided to stop raising interest rates, an outcome that is always good for the precious metal. Gold shops did a roaring trade for the rest of the year, and after the last rings, bracelets and necklaces were melted down for cash, gold recycling in 2019 ended up 11% higher than the previous year – and the most since 2012!

Unsurprisingly, gold recycling was strongest in countries with weak currencies in relation to the US dollar, where physical gold holders rushed to capitalize on gains in the local gold price. This included Iran, Turkey, southern Asia and southeast Asia. In India, the gold price in rupees gained 24% between the end of 2018 and year-end 2019.

The takeaway? If gold recycling in 2019 hadn’t been so high, owing to strong gold prices (spot gold gained 18% in 2019), total gold supply would likely have been in a significant deficit, not a 2% surplus.

Indeed the Gold Council is quick to point out that 2019 supply of 4,776 tonnes was 2% higher than 2018, apparently torpedoing the argument for peak gold. But wait! It turns out that 2019 mined gold, 3,463 tonnes, is 1% less than 2018. No big deal, until you read that last year was the first since 2008 that there has been a decline in gold output. That means 2018, a record year for gold production, was the last year that gold output rose compared to the previous year – a trend that has held since since 2008, and for most of the last 100 years except for 2016 – an outlier year.

For over a decade I’ve been saying that one of these years the industry will reach peak gold, for all the reasons I’ve been writing about: the depletion of the major producers’ reserves, the lack of new discoveries to replace them, production problems including lower grades, labor disruptions, protests, etc.

Turns out I was right – that year was 2018. The following year, gold output starts falling, and we believe, will continue to fall further.

To review, annual mine production in 2019 was 3,463 tonnes – the first annual decline in over 10 years. And that was in the face of record gold buying by central banks (whose reserves grew by 650 tonnes – the second highest total in 50 years), and record investment in gold ETFs (buying continued for the first three quarters then dropped off in Q4, when gold became too expensive).

Gold supply increased, as we’ve mentioned before, from recycling jewelry – taking advantage of high prices – and hedging by producers – again taking advantage of high prices.

The WGC report breaks down reasons for the decrease in mined gold output. This is very interesting because it tells us where the “softness” in gold production lies, and whether this trend is likely to continue.

We find the mine with the most impact on gold production was Grasberg in Indonesia. The largest copper mine in the world also produces significant gold. But Grasberg is undergoing a major transformation, from an open pit to an underground mine – the above-ground reserves, including the high-grade ore, has been mined out. We know that capital spending on the expansion is expected to average $0.7 billion per year, meaning we should continue to see downward pressure on Grasberg output for the duration of the 4-year project.

Due to Grasberg’s lower production, Indonesia saw the largest year on year gold output decline in the third quarter – down 41%.

In China, gold production fell 6% last year, for a third consecutive year. The largest gold-mining country is cracking down on mines with poor environmental records, a trend that is likely to continue, considering that Beijing is always sensitive to the concerns of a populace that has shown a historical willingness – witness recent explosive events in Hong Kong – to rise up.

Strikes in South Africa, especially during the first half of the year, curtailed production well into the third quarter, and in Latin America, disputes between local communities and contractors weighed on output, the report states. Peru’s third-quarter production lagged 12% due to falling grades. Chile and Argentina are seeing a wave of social unrest due to real and perceived inequality – mining unions are not immune.

Of course countries where gold production decreased were offset by those that managed to increase output of the yellow metal. Russian gold mine production was up 8%, and West Africa continued to surpass South Africa, whose gold fields are in structural decline. The country produces 83% less gold than it did in 1980, despite having the second-largest reserves in the world, and lost its continental gold output crown to Ghana in 2018.

Australia pumped out 3% more gold in 2019 owing to higher production at its many gold mines and the ramp-up of projects like Mount Morgans and Cadia Valley. However it’s important to note that Australia’s day in the sun as the world’s second biggest gold producer may soon be setting.

ABC News quotes analysts at S&P Global Intelligence, who say the country’s aging gold mines are running out of ore and not enough discoveries are being made to replace them. The analysts predict output will fall by more than 40% over the next five years and that Canada and Russia will overtake Australia – despite it having the world’s most gold reserves. Output is also expected to take a serious hit from droughts, which are forcing authorities to implement water restrictions.

We know that gold production is falling, mostly because of depleted reserves (expansions restricting output and unexpected closures play roles too), and a lack of new gold discoveries to replace them.

My suggestion for gold companies looking to acquire fresh reserves and resources, is to mine copper, specifically, copper-gold porphyries or large sedimentary copper deposits that also contain gold, silver or even platinum-group-elements (PGE metals rhodium and palladium are both trading much higher than gold at the present time).

The CEO of Barrick Gold makes much the same argument in an article this week in the Financial Post. Here’s Bristow, the former head of South Africa’s Randgold before it was acquired by Barrick last year, talking about Freeport-McMoran and its monstrous Grasberg copper-gold mine in Indonesia, being a potential takeover target, as the world’s second biggest gold company continues to accumulate assets:

Mr. Bristow recently described copper as a “strategic metal” because of the role it would play in the shift to a greener economy. “The new, big gold mines are going to come out of the young geologies of the world,” he said. “And in young rocks, gold comes in association with copper or vice versa.”

Whether or not copper is a “strategic metal” is debatable, but the real reason Bristow is talking up copper is because Barrick, and other major gold miners, need copper-gold deposits to help them overcome the depletion dilemma they are all facing.

A 2018 report from S&P found that 20 major gold producers had to cut their remaining years of production by five years, from 20 to 15, based on falling reserves.

Kitco reported on findings by BMO Capital Markets that global gold production is expected to keep dropping. “When we look out over the next five years, there are very few large scale new gold projects earmarked to come on-stream,” the BMO analysts said. “The only large-scale gold projects that we see as probable to enter the top 10 producing gold mining operations by 2025 are the Donlin Creek project, owned by Barrick and Novagold, and Sukoi Log owned by Polyus Gold.”

Another interesting stat: The 10 largest gold mines operating since 2009 will produce 54% of the gold as a decade ago – 226 tonnes versus 419 tonnes.

It’s not surprising that gold companies are finding it tougher to add to reserves.

According to McKinsey, in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the gold industry found at least one +50 Moz gold deposit and at least ten +30 Moz deposits. However, since 2000, no deposits of this size have been found, and very few 15 Moz deposits.

Any new deposits will cost much more to discover. This is because they are in far-flung or dangerous locations, in orebodies that are technically very challenging, such as deep underground veins or refractory ore, or so far off the beaten path as to require the building of new infrastructure from scratch, at great expense. The costs of mining this gold may simply be too high.

Moreover, gold grades have been declining since 2012, meaning more ore has to be blasted, crushed, moved and processed, to get the same amount of gold as when the grades were higher, significantly adding to costs per tonne.

Add to this the practice of high-grading where, instead of mining a deposit as it should be, economically, by extracting, blending both low-grade and high-grade ore at a given strip ratio of waste rock to ore – the company “high-grades” the orebody by taking only the best ore, leaving the rest in the ground.

Totaled up, these factors explain Barrick combining with South Africa’s Randgold, the Barrick-Newmont joint venture in Nevada, the $10 billion fusing of Newmont and Goldcorp, Newcrest’s 70% purchase of Imperial Metals’ Red Chris mine in British Columbia, and other 2019 examples of gold M&A.

According to the Refinitiv Eikon database, gold-mining companies in 2019 spent $30.5 billion on 348 merger or acquisition deals, nearly $5 billion more than in 2010, the height of the mining supercycle.

Knowing all this, ie., the record amount of M&A in the gold sector as companies increasingly mine out their reserves and fail to replace them with multi-million-ounce deposits, sending gold miners on a shopping spree to acquire smaller companies’ assets, makes it easier to appreciate why Bristow is so bullish on copper – and it has nothing to do with its green credentials.

Copper-gold porphyries and sedimentary copper deposits offer both size and profitability.

They are two of the few deposit types containing precious metals that have both the scale and the potential for decent economics that a major mining company can feel comfortable going after to replace and add to their gold or silver reserves.

Porphyry orebodies are usually low-grade but large and bulk mineable – they typically contain between 0.4% and 1% copper, with smaller amounts of other metals such as gold, molybdenum and silver.

There are two factors that make these kinds of deposits so attractive. First, by focusing on profitability and mine life instead of solely on grades, lower costs realized by economies of scale can offset the lower grades. This results in almost identical gross margins between high- and low-grade deposits. Low-grade can in fact mean big profits for mining companies – copper-gold porphyries offer both size and profitability.

The second factor affecting the profitability of these often immense deposits is the presence of more than one payable metal ie. for gold miners using copper by-product accounting, the cost of gold production is usually way below the industry average. (the copper credits off-set the gold mining costs per ounce)

The economics of mining porphyries comes down to by-product accounting. Here’s how it works, using Barrick as an example.

As a gold miner, Barrick needs to replace its gold reserves as they’re mined out. If, instead of a gold deposit, Barrick acquires a copper-gold porphyry, by-product accounting takes place – because the deposit not only has gold but copper, maybe molybdenum, and other metals too. The copper and moly by-products are mined, processed and sold – with by-product revenues put against production costs. This allows the gold company to mine the gold at three-quarters the cost of a gold-only deposit, or half, even 100% – in which case the miner is using the revenues from by-product metals to mine gold for free!

An interesting note to AOTH readers: I made these comments in 2009, on the suitability of acquiring copper-gold porphyries as a way for gold miners to increase their reserves. So I felt some satisfaction in reading the CEO of Barrick Gold making much the same argument in an article this week in the Financial Post – 11 years later.

In mining, costs per ounce can make or break a company. Imagine Barrick not only adding to its gold reserves, but lowering its costs per ounce, to below the industry average, through the sale of by-product metals. Barrick’s financials turn up rosy, and CEO Bristow ends up looking like a hero!

Yet from what we’ve read in the Financial Post, Bristow doesn’t want to go after porphyries – which hold 20% of the world’s gold reserves and are, in our opinion, a no-brainer to develop. Instead the CEO of the world’s second-largest gold company says he’s looking at Grasberg as a potential take-over target. A mine that, while still claiming the title of world’s largest copper mine, has depleted all its high-grade, above-ground ore. What’s left underground will likely be more costly to extract.

Instead, we humbly submit a better solution. Mr. Bristow, if you’re reading this, how about taking a look at a junior resource company that already owns one of these coveted copper-gold porphyries or large sedimentary copper-silver deposits in “young rocks”, that you could acquire, for pennies on the dollar?

(By Richard Mills)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments