COP aims to end coal, but the world is still addicted

Never in human history has a ton of coal cost more. Governments and utilities across the globe are willing to pay record sums to literally keep the lights on. That’s the bruising reality that global leaders must face at the high-stakes climate talks in Glasgow this month as hopes fade for a deal to end the world’s reliance on the dirtiest fuel.

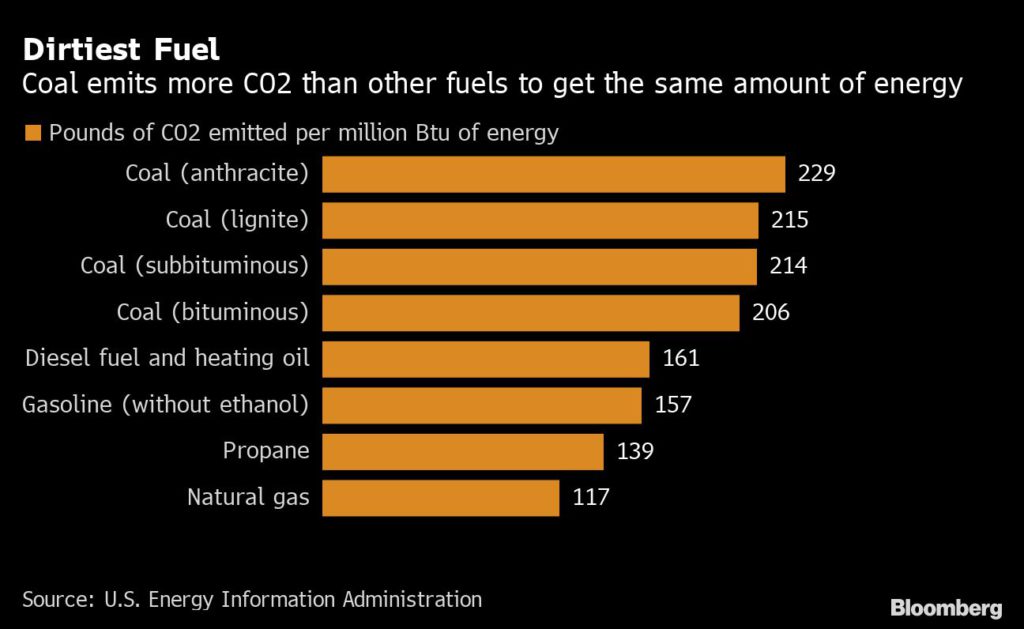

The burning of coal represents the biggest single obstacle to meeting the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5C. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres calls it a “deadly addiction,” and COP26 president Alok Sharma has urged leaders to “consign coal to history.”

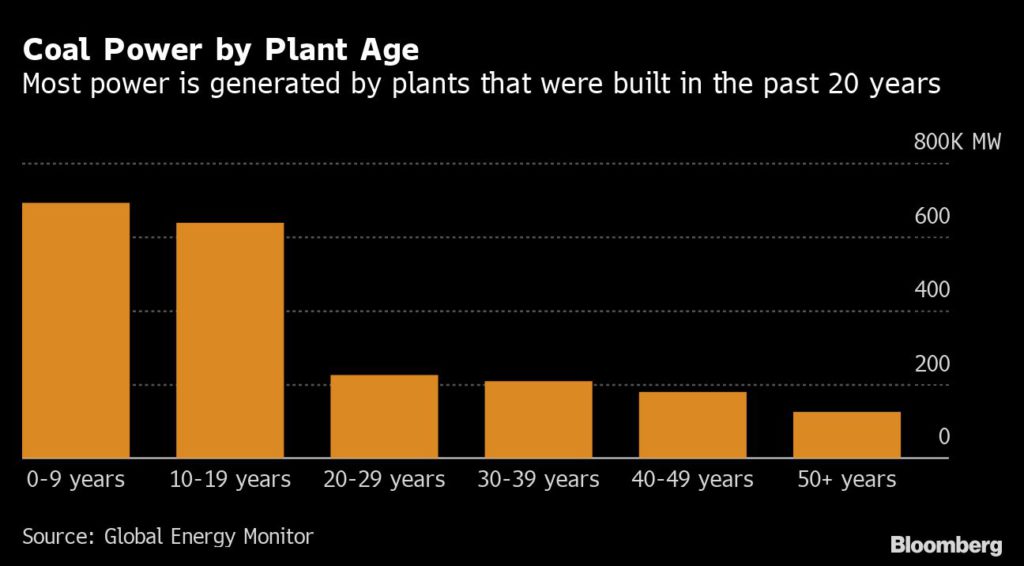

There’s been some progress already — the global pipeline of new coal-fired power plants has shrunk almost 70% since 2015. President Xi Jinping announced last month China will stop building coal-fired power plants abroad, while Germany now wants to end its use of coal by the end of this decade and more than 40 countries have committed to “no new coal.” Renewable energy is expanding sharply.

But the dramatic rally in prices in recent weeks shows ever more clearly that it’s nowhere near enough. Humanity remains deeply dependent on coal.

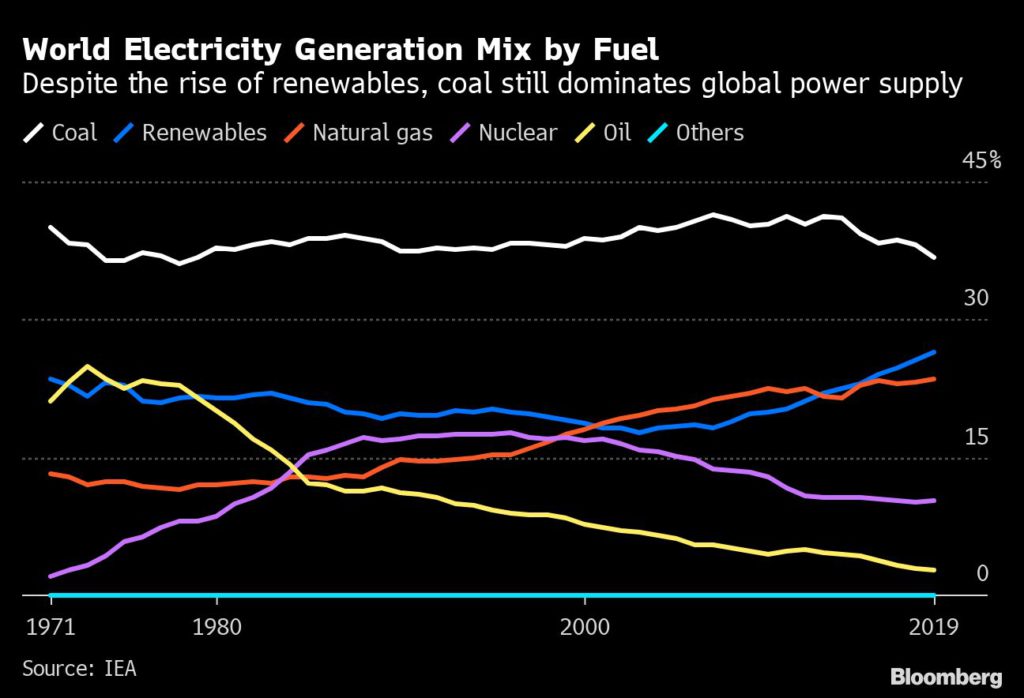

For one thing, coal continues to dominate the world’s total electricity generation mix by a large margin. There are still more new coal plants being built than old ones switching off, and the International Energy Agency projects emissions from the power sector will reach a record in 2022 as coal-power use surges.

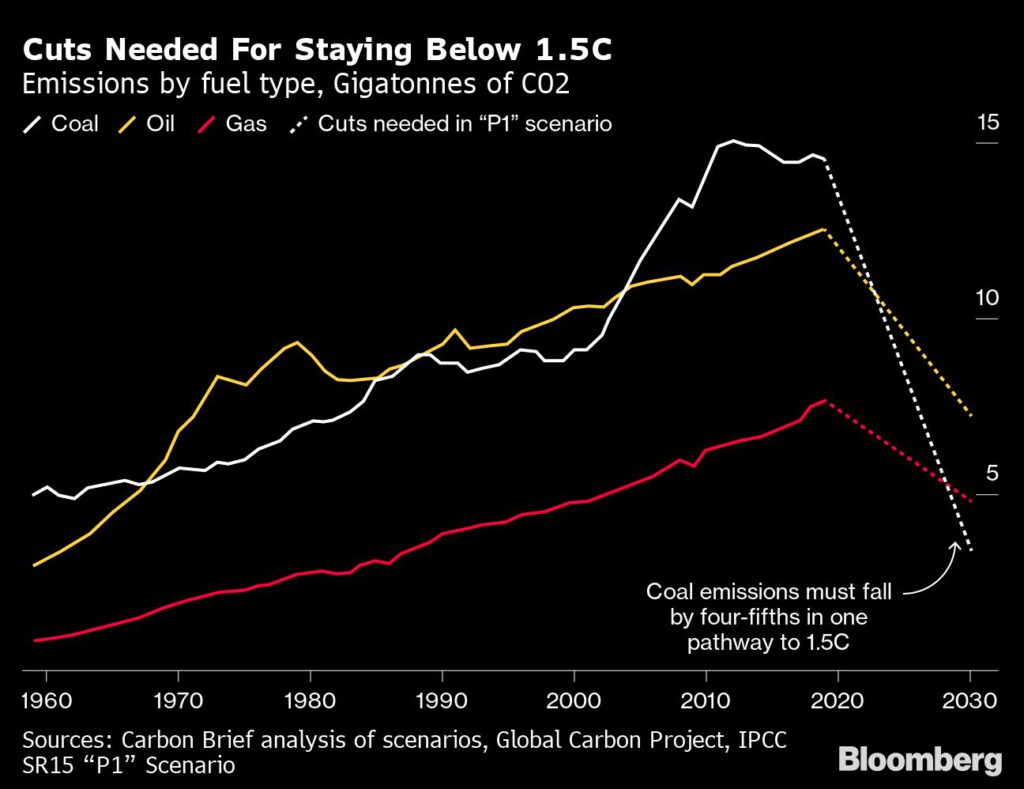

To meet the 1.5C target, emissions from coal need to drop this decade about twice as quickly as pollution from oil and gas, according to Carbon Brief analysis of global emissions scenarios. For example, in one of the dozens of potential pathways to achieving the target, coal emissions would need to fall by 79% from 2019 to 2030.

That’s a gargantuan challenge, made even more daunting given this year’s surging appetite for coal to generate electricity. A global power crunch and shortage of natural gas have driven up coal demand, sending prices soaring to records in nominal terms and squeezing supplies.

And while production has been constrained as the biggest mining companies retreat from coal under pressure from investors, the high prices are likely to attract private and smaller players who don’t face the same constraints, meaning there’s more coal available to burn.

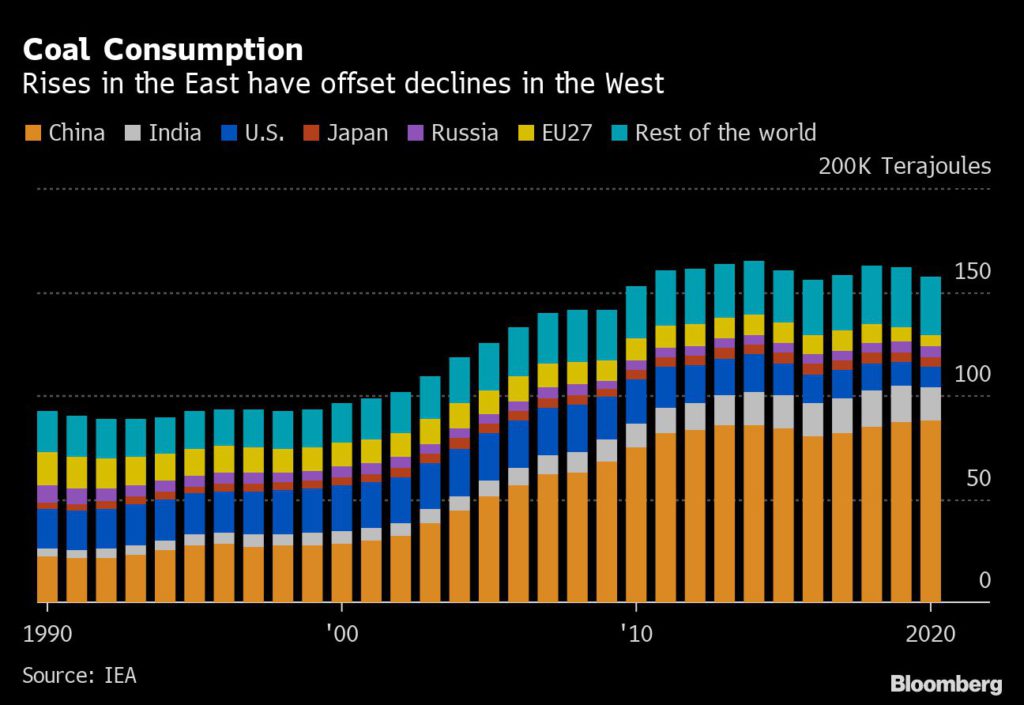

Like almost every other aspect of the global economic story, coal demand in the past three decades has been a story about the rise of China. As the world’s manufacturing base moved east, so did the demand for cheap, easy-to-build power needed to fuel everything from steel plants to cities.

Since 1990, U.S. coal demand has halved, largely because power companies have turned to gas instead. European demand has dropped by almost two-thirds. Yet these gains have been easily offset by China’s growth. Its consumption was roughly on par with the U.S. when the Cold War ended but now stands at a stunning 87,638 terajoules, more than half the world’s total demand.

It’s not just China. India now burns more coal than Europe and the U.S combined and miners are betting on rising demand over the next decade from countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh and Indonesia, although pollution concerns and cheaper alternatives threaten to derail those plans.

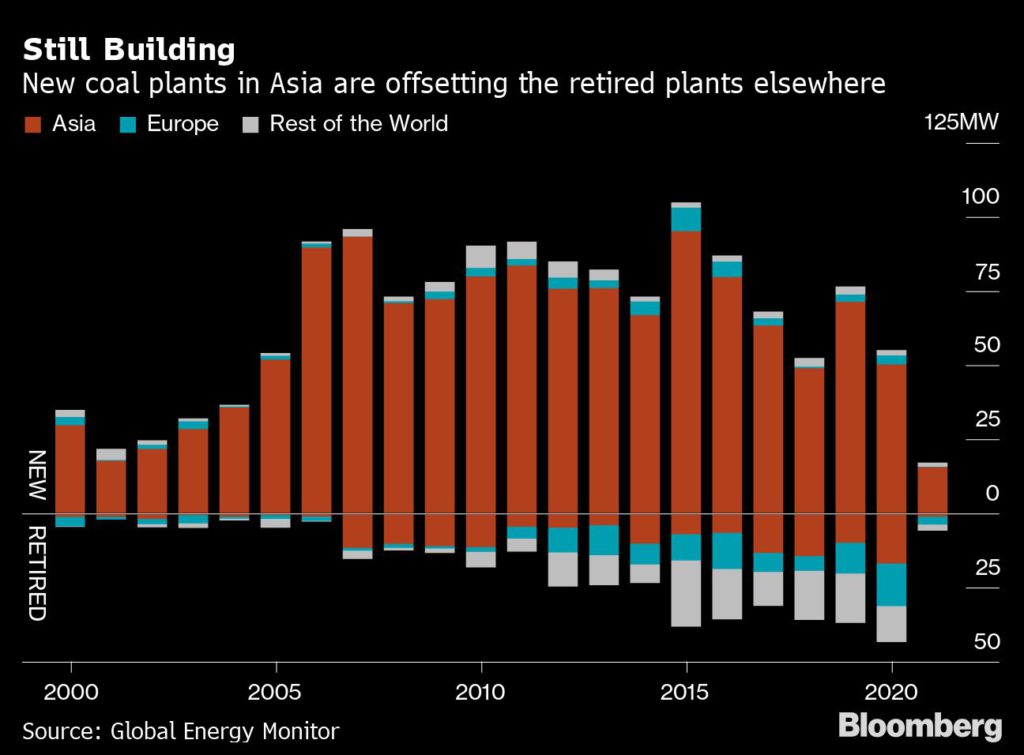

Nothing highlights coal’s migration from west to east better than where power stations are being retired and built. For decades, plants have been closing across Europe, phased out by a potent combination of climate policy pressure, tumbling renewables costs and a flood of cheap gas.

The U.K., the original poster child for the coal-powered Industrial Revolution, went 67 consecutive days without burning any of the fuel last year. Spain alone closed seven of its 15 coal plants in 2020. In total, half of the region’s coal plants have closed or will close by 2030.

This year, the power crisis in Europe has exposed vulnerabilities in the system. The U.K. has been particularly hard hit after calm weather hit wind-power supply, exacerbating the effects of a wider regional gas shortage.

Meanwhile, closures in Europe have been easily offset by new builds across Asia. China, India, Indonesia, Japan and Vietnam plan to add more than 600 coal power units. China alone is currently building or planning coal power plants that are the equivalent of six times Germany’s entire coal-burning capacity.

The 2010s have been the decade of renewable energy. Rapid increases in technology, hefty government subsidies and tumbling costs have seen seas of solar panels and forests of wind turbines become commonplace.

Yet despite the huge renewable rollout, burning coal remains the world’s favorite way to make power, accounting for 35% of all electricity . While the renewables share has grown from 20% to 29% of the global mix in the last decade, coal only lost 5 percentage points in the same period.

Coal is the single biggest source of carbon dioxide emissions and the electricity sector’s biggest source of greenhouse gases. While global CO2 emissions fell by the most on record last year, this was driven by a collapse in demand driven by the pandemic, rather than a step-change in fossil fuel use. Global emissions are surging back this year as the economy recovers and power crunches ripple around the world.

(By Thomas Biesheuvel and Samuel Dodge)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments