Commodities to veer between China hopes, pandemic fears

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Clyde Russell, a columnist for Reuters.)

If 2021 was a year of volatility and uneven performances for commodities, then 2022 is shaping up as a rinse and repeat as uncertainty over the recovery from the coronavirus pandemic remains the dominant theme.

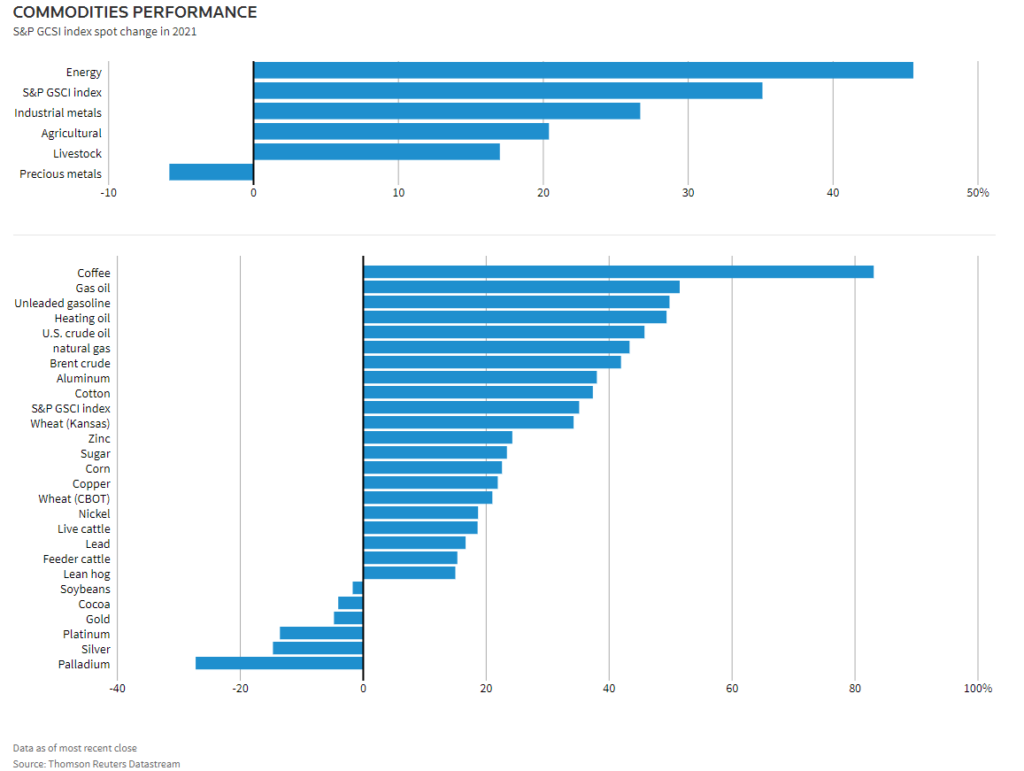

On the surface, commodities had a strong year, outperforming other asset classes with the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index jumping 35% this year, beating the US equity index S&P 500 for the first time in a decade.

But that headline figure doesn’t capture just how volatile the year was for major commodities, with several hitting record highs before plummeting back to earth, while others experienced large swings amid countervailing demand and supply narratives.

What wasn’t a surprise in 2021 was the outsized role played by China in many commodity markets, given the world’s second biggest economy’s status as the top importer of crude oil, iron ore, coal, copper and in all likelihood liquefied natural gas (LNG) as well.

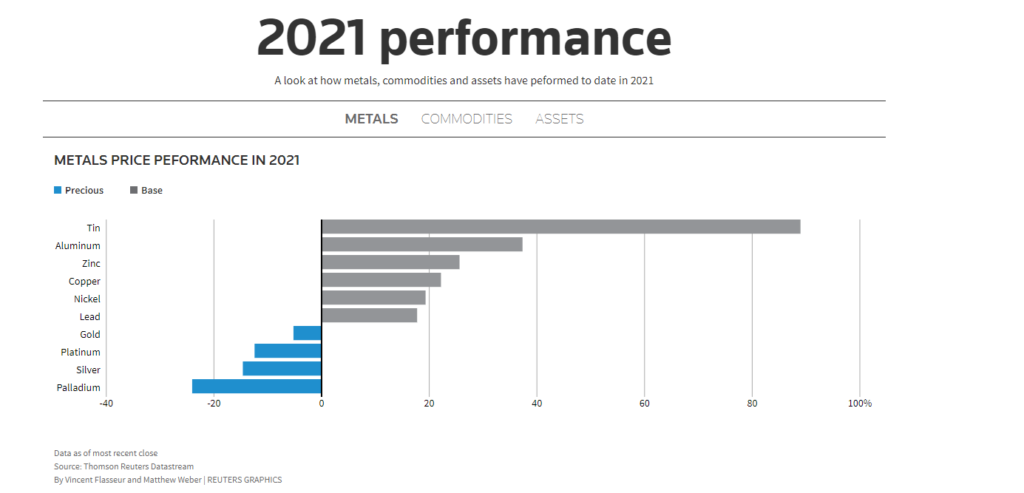

The sector where China’s impact was most keenly felt was metals, with spot iron ore surging to an all-time high of $235.55 a tonne in May as its steel mills cranked out record amounts of the construction material.

The same Chinese demand also boosted copper, with London contracts rising to a record $10,747 a tonne in May.

But while copper managed to hold on to much of its gains, iron ore plunged as China changed course on steel output, actually enforcing an official target that 2021’s output would not exceed 2020’s, and the spot price, as assessed by commodity price reporting agency Argus, fell as low as $87 a tonne by November.

It has since recovered, to $122.70 on Monday, but will likely end the year below the close of $159.90 on the last day of 2020.

The recent recovery is premised on a market view that may well end up shaping commodity prices for 2022, namely that China is once again going to open up the stimulus taps to boost a flagging economic recovery.

If this is the case, then iron ore and metals stand to be the major beneficiaries, as well as coking coal used to make steel.

Energy strength

Energy commodities enjoyed a strong year, with Australian benchmark Newcastle thermal coal hitting a record high $252.72 a tonne in mid-October.

Once again, China was the driver, even though it is maintaining an informal ban on imports from Australia as part of a political dispute.

China largely scored an own goal by idling some of its domestic coal mines for safety reasons, leading to lower output just as demand for electricity was recovering from the pandemic.

This led to China’s traders trying to snatch up every available non-Australian coal cargo, which pushed prices higher, eventually dragging Australian prices along as India was forced to switch from Indonesian coal.

Coal prices have moderated since the record as both China and India, the world’s second-biggest importer, ramped up domestic output.

However, thermal coal may enjoy a solid 2022 assuming economies across Asia manage to successfully transition to the stage of living with coronavirus.

Strong regional energy demand is also likely to keep LNG well bid, especially over the northern winter, although constrained supply may see the usual price declines in the shoulder seasons of spring and autumn be weaker than normal.

Crude oil is one major commodity where China’s influence appears less marked even though it is the world’s biggest importer of the fuel.

The main driver of crude in 2021 was the supply discipline imposed by the OPEC+ group of exporters and increasing demand, especially in North America and Europe.

But China still exerted influence on the crude market, mainly by not importing as much in 2021 as it did in 2020.

China’s crude oil imports are likely to fall by about 7% in 2021 and it has gone from building inventories by around 1.2 million barrels per day in 2020 to virtually no stockpile additions this year.

A strong economic rebound in 2022 should result in China buying more crude but it is also likely that the phase of inventory building is coming to an end, thereby removing a source of demand growth for the global market.

What remains uncertain is just how the coronavirus pandemic will play out, whether countries will rely on high vaccination rates and open up their economies, or will they be like China and try for an elimination strategy.

This uncertainty probably makes volatility the only certainty.

(Editing by Robert Birsel)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments