Column: Zinc treatment charges jump after 2022 smelter bottleneck

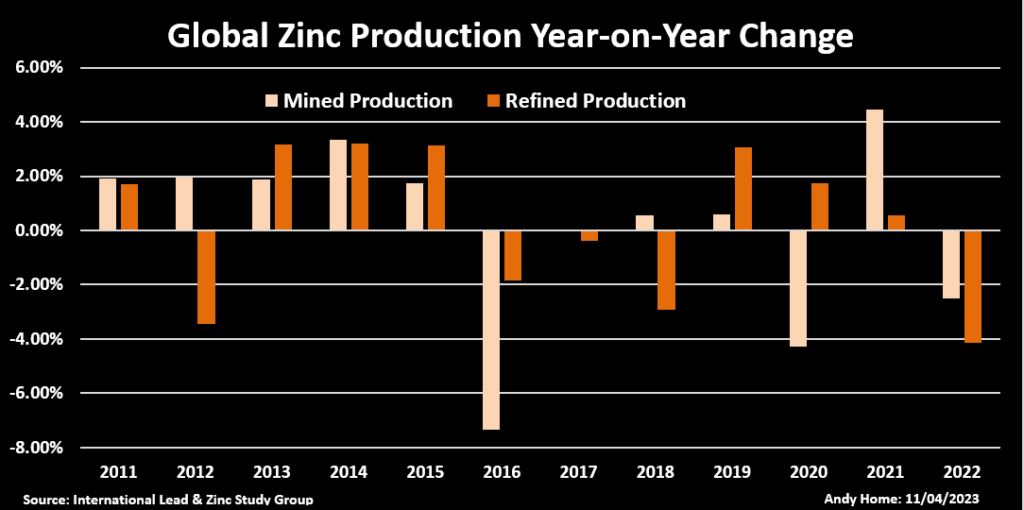

The zinc market was defined by smelter woes last year with global refined metal production dropping by 4.1% relative to 2021, according to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG).

It was the sharpest fall in world zinc output since 2009, a year of massive disruption caused by the global financial crisis and ensuing collapse in industrial metal prices.

Zinc usage was also weak last year, sliding by 3.3% from 2021 levels as China’s construction sector, a major user of the metal in the form of galvanized steel, struggled to regain lost momentum.

But the smelter bottleneck was severe enough to generate a global supply shortfall of more than 300,000 tonnes, according to ILZSG.

Will this year be any different?

A sharp rise in the annual benchmark smelter processing fee should incentivize a turnaround in metal production. The scale of the rebound, however, will also depend on structural issues, particularly power availability in Europe and China.

Out-of-synch supply chain

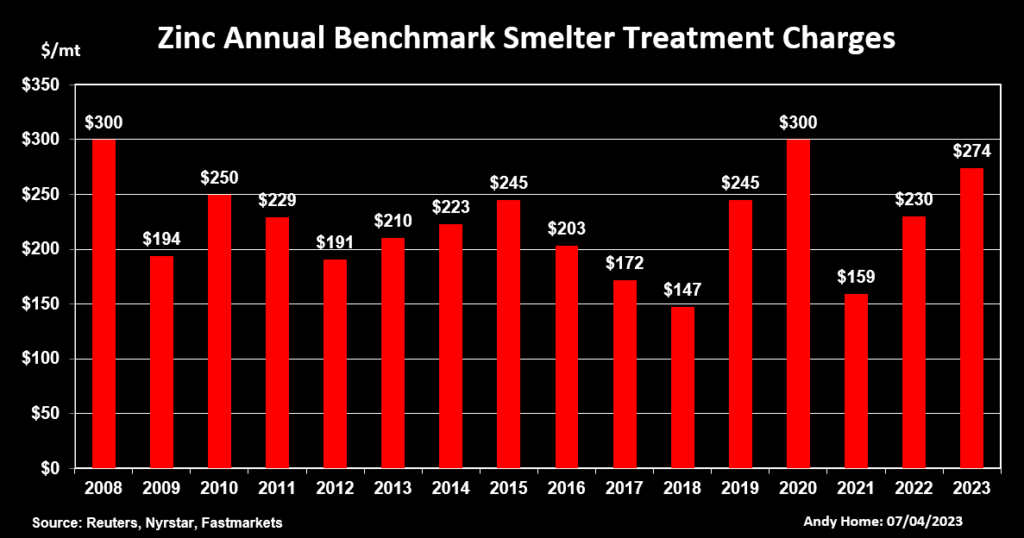

This year’s benchmark treatment charge, the fee a smelter earns for converting mined concentrates into metal, has been set at $274 per tonne, up from $230 in 2022 and $159 in 2021.

The benchmark, first reported by Fastmarkets, was settled between Korea Zinc and Teck Resources and includes price participation above an LME price of $3,000 per tonne.

It’s the second highest benchmark in a decade, eclipsed only in 2020, when it was set at $299.75 per tonne.

Expectations that year were for a long-awaited surge in mine supply to wash through the market, allowing smelters to reap the rewards of a raw materials glut.

Things didn’t work out that way. Global mine production slumped by 4.3% in 2020 as Covid-19 lockdowns hit output in key producer nations such as Peru.

Smelters were largely unaffected. The resulting unexpected tightness in the concentrates market saw the benchmark nearly halve in 2021.

Zinc’s supply-chain dynamics have since inverted.

Mine supply staged a strong post-Covid recovery and although it weakened again in 2022, it was still more resilient than global smelter performance.

The mismatch between zinc mine and smelter production has led to a two-year build of concentrates stocks and surging spot treatment charges in the Chinese market as miners compete to find a home for their output.

The jump in the annual benchmark reinforces the spot market signal and should, in theory, provide every incentive for smelters to lift output this year, closing or reversing the refined metal supply gap.

Smelter recovery?

There are signs that the incentive is already working.

China’s imports of zinc concentrates have been rising since August last year and were up a hefty 30% in the first two months of 2023.

The country’s production of refined zinc jumped by 6.6% in the first three months of this year after declining by 1.8% in 2022, according to data provider Shanghai Metal Markets.

In Europe, where production slumped last year due to high energy prices, there are signs of renewed life. The Auby smelter in France returned from care and maintenance last month, according to operator Nyrstar.

However, the company, controlled by Trafigura, noted that it “continues to manage the production at its European sites” in the face of continuing uncertainty around power pricing.

It’s a warning that not all last year’s smelter problems are going to be resolved by a higher processing fee alone.

Glencore’s Nordenham plant in Germany remains on care and maintenance as does the company’s primary production line at Portovesme plant in Italy.

Although last year’s power price surge has abated, the uncertain outlook for the coming year, particularly next winter, complicates the economics of reopening idled capacity.

North American refined capacity has taken a permanent hit with the closure last year of the Flin Flon smelter, while the Valleyfield plant, operated by Noranda Income Fund , is struggling with technical problems.

A six-week maintenance shutdown at the end of last year has stabilized operations, the company said, but “will not fully address underlying operational issues”. That might require a more protracted shutdown, but timing will not be before 2024 as options are evaluated.

Even in China, it’s worth remembering that part of last year’s production drop had nothing to do with market incentives but rather power availability. Drought in hydro-rich Yunnan and Sichuan provinces led to mandatory downtime for many heavy power users, including zinc smelters.

Bear narrative (again)

The higher treatment charge benchmark, combined with still elevated premiums for refined zinc in the physical market, should generate a burst of higher metal production this year.

It’s why analysts are generally downbeat on zinc’s prospects. Reuters‘ poll of analysts at the start of the year captured a median expectation for prices to decline in both 2023 and 2024 as mine surplus is converted to metal surplus over the course of the coming months.

This of course is what everyone was expecting back in 2020, when the treatment charge benchmark jumped to a decade high on the prospect of a mine supply wave that didn’t arrive until a year later.

This time around it’s smelter performance that will determine whether the bear narrative around zinc turns out to be correct.

The market incentive for higher smelter output is now confirmed by this year’s treatment charge benchmark. But structural problems, particularly power availability in Europe and China, may yet act as a powerful brake.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Jane Merriman)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments