Column: West plugs defences as China cranks up aluminum output

China’s primary aluminum smelters are producing record amounts of metal and the domestic market surplus is spilling out of the country in the form of semi-manufactured products.

This sudden acceleration in “semis” exports is rekindling the flames of a long-simmering trade conflict.

Western countries have repeatedly accused China of unfairly subsidizing its aluminum and steel sectors, claiming the country’s excess capacity is swamping global markets.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) said last month that it was unable to get a clear picture of China’s financial support for key industrial sectors due to an “overall lack of transparency”.

With no means of negotiating a multilateral remedy, countries are increasingly turning to unilateral tariffs to protect themselves from the renewed Chinese flood.

Cranking up the volume

China’s production of primary aluminum hit a fresh monthly peak of 3.690 million metric tons in July, according to the International Aluminium Institute.

Output rose 4.9% on a year-on-year basis in the first seven months of 2024 and the collective run-rate reached an annualized 43.5 million tons in July.

The country’s production rate is closing in on the government’s 45-million-ton annual capacity cap now that increased rainfall in the hydro-rich province of Yunnan has enabled smelters to restart capacity that was idled earlier this year.

The problem is that China’s domestic demand hasn’t been strong enough to absorb this much aluminum.

Although demand remains resilient in new energy applications such as solar panels and electric vehicles, domestic appetite is being constrained by weakness in both the construction and broader manufacturing sectors.

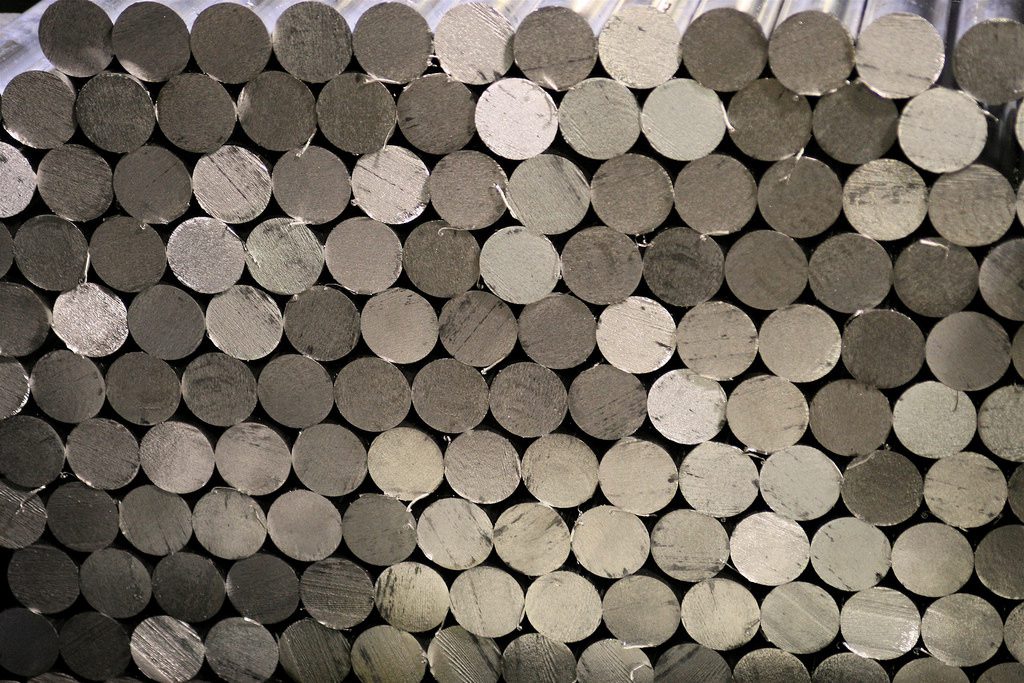

The surplus aluminum is being exported in the form of semi-manufactured products such as plate, rods, tubes and foil.

Semi-manufactured product exports fell 14.9% last year but rebounded by a similar margin to almost 3.0 million tons in the first half of 2024, according to LSEG trade data.

Outbound shipments of 566,400 tons in July were the highest monthly tally since July 2022.

Fortress America

The US has led the push-back against Chinese exports of both aluminum and steel in recent years.

There have been multiple anti-dumping and countervailing duties imposed on Chinese products, overlaying the broader 10% aluminum import tariffs initiated in 2018 using so-called Section 232 national security powers.

None of which has halted the flow of Chinese products into the US market. China exported 210,000 tons of aluminum to the US last year, making it the sixth-biggest destination by volume.

The Biden administration is now preparing to up the ante.

In April it asked the Office of the US Trade Representative to consider tripling duties to 25% on both Chinese steel and aluminum products, using Section 301 powers designed to protect the country from “unfair” trade practices.

Mexico and Canada, which both enjoy exemptions from the Section 232 tariffs, are also being corralled into action.

Mexico was the top destination for Chinese aluminum product exports last year with outbound shipments of 511,000 tons, according to LSEG data. Another 200,000 tons were shipped to Canada, making it the seventh-largest export market.

Both countries have been accused of acting as transshipment corridors for Chinese aluminum surplus in the form of remelted product.

Canada will start imposing a 25% surtax on imports of both Chinese aluminum and steel on Oct. 15.

Mexico was due to lift duties by a similar amount but changed its mind in May. The government argued it would have placed too high a burden on the country’s aluminum consumers.

The US has responded by requiring aluminum product imports from Mexico to be accompanied by a certificate of analysis proving they have not been derived from Chinese metal either at the smelting or casting stage of the production process.

Those that fail to satisfy the country of ultimate origin test will no longer be exempt from the Section 232 tariffs.

Fractured world

Others are following the US lead by shoring up their own trade defences against Chinese imports.

India’s trade ministry has just recommended imposing an anti-dumping duty on aluminum foil imported from China after surging shipments from the neighbouring country captured nearly a third of India’s market share despite ample local production capacity.

The European Union has, like the US, already hit Chinese aluminum imports with multiple product-specific anti-dumping penalties. But the carbon border adjustment mechanism, due to come into effect in 2026, will form another broader line of defence against Chinese aluminum, most of which comes with a relatively high carbon footprint.

The more aluminum China produces, the more tariff walls are going to be erected, as the West looks to protect its domestic supply chains from what David Bisbee, the US deputy permanent representative at the WTO, described as China’s “predatory” industrial policy aimed at global domination.

The WTO is proving to be an ineffective forum for resolving what amounts to a clash of systems between Western free market orthodoxy and China’s state-led industrial model.

So countries are increasingly left with no other choice but to take their own unilateral actions, fracturing what was once a highly globalized market.

The cracks will only widen if China’s exports keep rising.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Paul Simao)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments