Column: Unloved lead gets to join the Bloomberg commodity A-list

Lead will become the 24th commodity to be included in the Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM), joining its London Metal Exchange (LME) peers aluminum, copper, nickel, and zinc.

The London three-month lead price jumped almost 10% to $2,019.50 per tonne on Friday’s news, although it’s since pared its gains to a current $1,965.

The reaction is understandable if a little premature. Although lead will have only a 0.936% weighting in the index, the lowest of any of the base metals, it will still translate into fund buying at the start of next year as asset managers adjust to the new weightings.

Perhaps equally important is what inclusion says about a metal widely assumed to be heading for obsolescence as lead-acid batteries succumb to the relentless march of lithium-powered electric vehicles (EV).

The frequent reports of lead’s death, however, continue to be much exaggerated.

Lead’s not dead

It’s not easy being a lead market analyst.

“One of the frustrations (…) is people telling you constantly that lead is dead,” lamented Andrew Thomas, director for zinc and lead at Wood Mackenzie.

However, as he explained at the research house’s LME Week Seminar, what everyone forgets is that of the 80 million passenger vehicles produced last year “just about every single one had a lead-acid battery in them”.

And that includes the eight million electric vehicles produced. In the excitement around new battery metals such as lithium and cobalt, it’s easy to overlook the fact that EVs have a back-up lead battery for safety systems and to power in-car entertainment systems.

Lead-acid batteries need replacing every few years. Given an average vehicle life of 13-14 years, last year’s 80 million vehicles will still be requiring replacement batteries in the early part of the next decade.

Lead’s usage profile is one of unexciting but steady growth, driven by the need to meet demand for replacement batteries in an ever-growing global passenger fleet.

Economic significance

Supply has grown to match demand, global production of refined lead creeping up from under 10 million tonnes in 2010 to 12.38 million tonnes last year, according to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG).

The BCOM looks at five-year averages of exchange liquidity and production data to determine which commodities are included and at what weighting.

The idea is that selected commodities should be both important to the global economy and reflect the value placed on that role by financial markets.

Global lead production has grown sufficiently over the last five years to merit inclusion even though trading liquidity has decreased, according to a statement from Bloomberg.

BCOM determines base metals liquidity with reference to the LME lead contract, which saw volumes fall by 3.8% last year with a further 7.7% decline over the first nine months of this year.

Lead’s performance should be seen in the context of a 4.7% slide in total LME volumes last year and the broader drop in activity following the exchange’s nickel blow-out in March this year.

However, weak trading activity also reflects lead’s unloved status relative to sister metal zinc. LME zinc volumes are more than double those of lead, even though global production of refined zinc was only slightly higher at 13.85 million tonnes last year.

Bumpy ride

With replacement battery demand accounting for around half of global lead usage each year and recycled metal for around 60% of supply, lead’s market dynamics are quite different from the other industrial metals.

Batteries fail in boom times and bad, meaning lead is partly insulated from the economic cycle and has a history of shallower troughs but lower peaks than other LME metals.

The lead market, in other words, can be a bit boring.

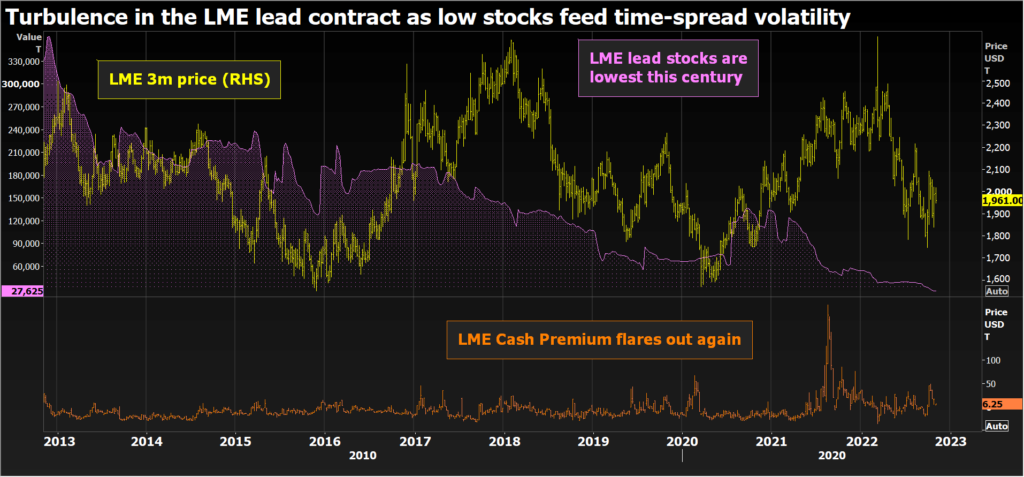

But not right now. It’s ironically going through a bout of turbulence just as it’s about to be elevated to commodity A-list status.

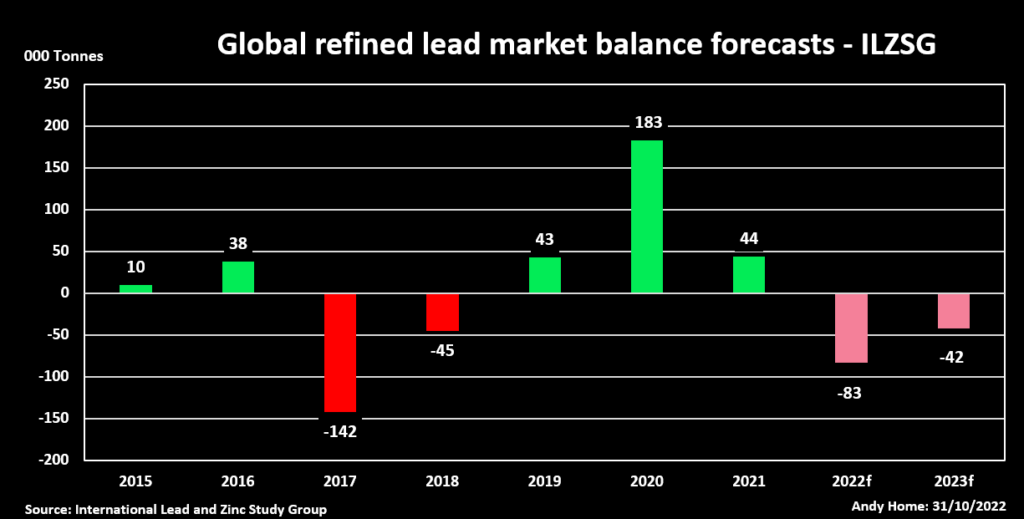

An unusual sequence of smelter disruption will cause global refined output to slide by 0.3% in 2022, according to ILZSG, which was expecting a 1.3% rise as recently as April.

European supply has been hit by the year-long outage due to flooding of Germany’s Stolberg plant, the loss of Russian imports due to sanctions and, most recently, the shuttering of secondary capacity in Italy.

ILZSG also noted falling production in North America, Turkey, South Korea and Australia, where planned maintenance works at Nyrstar’s Port Pirie smelter will halt production for two months in the fourth quarter.

The Group is now forecasting a global supply deficit of 83,000 tonnes this year and another 42,000 tonnes in 2023 before smelters catch up with demand.

LME stocks are super low at 27,625 tonnes, equivalent to less than a day’s worth of global consumption. That’s feeding time-spread tension, the cash premium to three-month metal CMPB0-3 flexing out to $48.50 per tonne last month, the widest it’s been this year.

Physical premiums are at record highs, Fastmarkets assessing that for U.S. Midwest delivery at 22.5 cents per lb (US$496 per tonne) over the LME cash price.

Western shortfall is being met by Chinese exports. China was a consistent net importer over the 2017-2020 period but flipped to net exporter last year to the tune of 93,000 tonnes. Net exports in the first nine months of this year have already almost exceeded that figure at 92,000 tonnes.

The flow of Chinese metal is expected to continue until supply and demand rebalance in Western markets.

These are turbulent times for normally sleepy lead and set an interesting backdrop to the fund buying that will follow the January reweighting.

That buying will also coincide with the northern hemisphere winter, a peak demand season for lead as cold weather makes batteries more prone to failure.

It’s just another distinctive quirk of the metal that refuses to go away.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Jane Merriman)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments