Column: Tin takes a breather but the calm may not last long

Tin’s roller-coaster ride has paused as the market navigates a period of weak demand and improved supply.

London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month tin has been treading water in a $23,700-26,800 range since the start of May.

Global exchange inventory has risen back above the 10,000-tonne mark for the first time since early 2021, largely thanks to a stocks build on the Shanghai Futures Exchange.

A depleted supply chain is refilling with Fastmarkets assessing the US Midwest premium at a mid-point $1,600 per tonne over the LME cash price, the lowest it’s been since March 2021.

None of which is a bad thing after last year’s extreme volatility. The London price hit an all-time high of $51,000 in March before imploding to a two-year low of $17,350 per tonne in November.

Tin’s tranquility, however, may be short-lived. LME time-spreads are tightening again and the three-month price, last trading at $26,760, is nudging the upper end of the recent range.

Although the demand outlook remains subdued, tin supply is facing two big threats, one from Myanmar and one from Indonesia, the world’s largest exporter.

Tin takes a demand hit

Almost half of the world’s annual production of refined tin is used in circuit-board soldering, meaning the consumer electronics industry is a core demand driver.

The electronics boom of 2021, when lock-downs meant more working and playing at home, has gone into reverse as hard-pressed Western consumers tighten their belts.

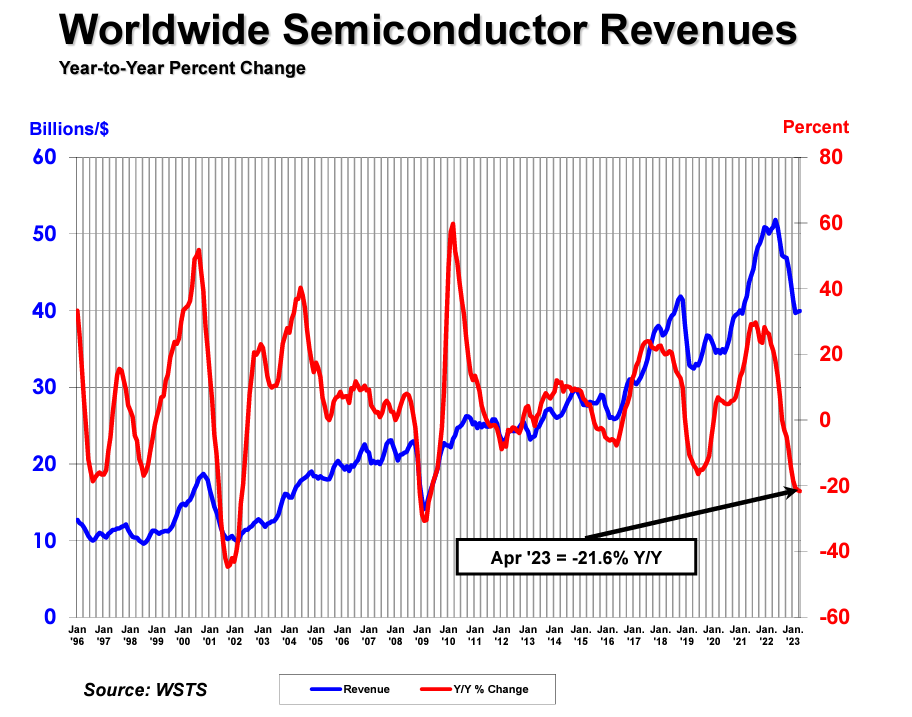

Global semiconductor sales, a proxy for tin soldering usage, were down by 22% year-on-year in April and are forecast by World Semiconductor Trade Statistics to fall by 10% over the year as a whole before rebounding by 12% in 2024.

Global tin supply, meanwhile, is now improving after an early-year drop in Indonesia shipments.

The annual export licensing round took longer than usual with exports down by 35% year-on-year over the first quarter. However, they accelerated to above 7,000 tonnes in both April and May, bringing the year-to-date total to 24,000 tonnes and reducing the year-on-year gap to 17%.

Peruvian production is also returning. Local producer Minsur reported a 54% slide in first-quarter production to 2,716 tonnes due to social unrest but was able to resume full operations over the course of March.

Myanmar mystery

However, the supply pipeline is facing a double threat of significant disruption.

The first is a suspension from Aug. 1 of mining in the part of Myanmar controlled by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the country’s largest armed ethnic group.

The Wa State accounts for around 10% of global mined tin production and is a major supplier to China, accounting for around 26% of the country’s demand last year, according to the International Tin Association.

Tin briefly spiked higher when the news first broke in April, but the subsequent price action suggests the market is doubtful the Wa State will halt completely one of its major revenue generators.

But a subsequent implementation plan, obtained by the ITA, suggests that is exactly what it is planning to do.

The suspension will allow a major audit of all tin mining and processing operations in the Wa State with the aim of resolving the interlinked problems of wasted resource, environmental damage and worker discontent.

No-one outside the UWSA has any idea how long the suspension will last but the authorities have mandated a “smooth demobilization process for mine workers”, which suggests it could be a while.

China’s imports of tin concentrates from Myanmar fell by 33% over the first four months of this year relative to 2022, causing total raw materials imports to slide by 29%.

The country’s smelters are already struggling with a shortfall of tin concentrates. Refined tin production fell year-on-year in May and Guangxi China Tin Group, the world’s sixth-largest tin producer, has just announced a 40-50 day maintenance break from the end of this month, according to the ITA.

Indonesia eyes export restrictions

The second major supply riddle is posed by Indonesia, which has made no secret of its ambition to restrict exports of refined tin to stimulate the build-out of downstream processing capacity.

The country’s template is its nickel sector. An export ban on unprocessed ore has transformed Indonesia into the fastest-growing production hub for battery-grade nickel.

The problem with tin, however, is that Indonesia long ago banned the export of unprocessed ore as part of an extended campaign to control its artisanal and independent producers.

Indonesia currently only has enough downstream capacity to absorb 5% of its domestic tin production, meaning that any restrictions will likely come in phases.

However, the country’s direction of travel is not in doubt even if the time-line is murky.

It’s noticeable that China has been stocking up on Indonesian metal. Imports jumped from just 3,500 tonnes in 2021 to 24,000 tonnes last year and have continued flowing to the tune of another 4,400 tonnes so far this year.

Peace while it lasts

Tin has been able to take a well-earned breather thanks to the poor state of consumer electronics demand and the rebuild in exchange inventory.

Most of the stocks, though, are located in China. LME inventory is still low at 2,020 tonnes, down by 975 tonnes from the start of January despite a regular stream of deliveries into exchange warehouse.

Metal has been arriving in response to renewed LME time-spread tightness. The benchmark cash-to-three-months period widened to a backwardation of $456 per tonne at the Tuesday close, the highest cash premium since July last year.

It’s still a long cry form early 2021, when tin was suffering from extreme scarcity and the LME cash premium flexed out to an unprecedented $6,500 per tonne.

But it’s a warning sign that there are turbulent waters beneath tin’s surface calm.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments