Column: Supply hits catch up with lead as LME stocks shrink

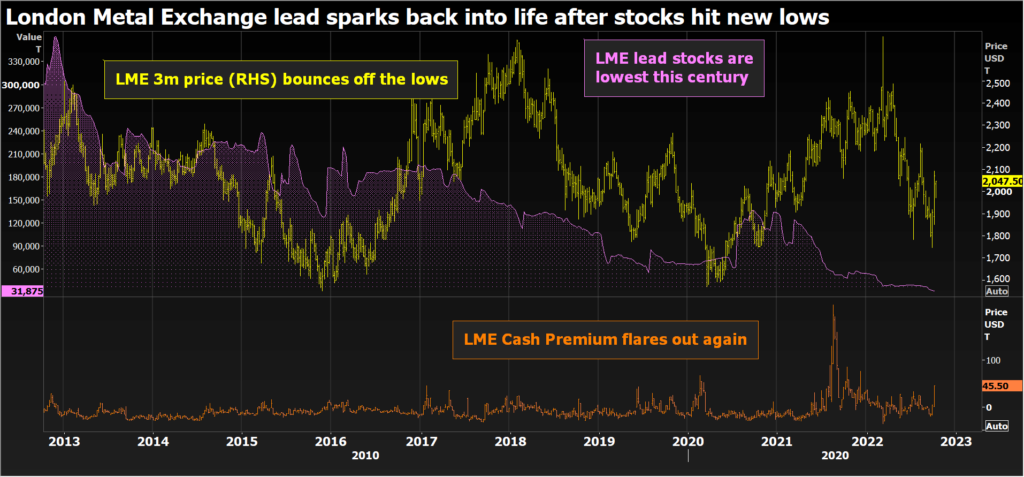

The lead market has sparked back into life after a raid on already low London Metal Exchange (LME) stocks.

The LME three-month lead price jumped 12% over the course of last week, hitting a near two-month high of $2,093.50 per tonne. Time-spreads are the tightest they’ve been this year, the cash premium over three-month metal widening to $45.50 per tonne.

The trigger for all the excitement was the cancellation of 17,125 tonnes of LME stocks in apparent preparation for physical load-out.

This has left available stocks in the LME warehouse network at just 10,900 tonnes, the lowest this century and equivalent to a few hours worth of global consumption.

The stocks grab appeared to catch off-guard a market that has been happy to short lead and buy zinc in a long-running relative value trade between the sister metals.

Zinc smelter closures in Europe have grabbed the recent headlines but lead supply has also been taking a growing number of supply hits.

European smelter problems

Lead refiners are less exposed to Europe’s rolling energy crunch than zinc smelters.

Macquarie Bank estimates that lead refining uses around 800 kilowatt-hours per tonne of metal, compared with 4,750 for zinc. (“Commodities Compendium”, Sep. 29, 2022).

However, persistently high gas prices across Europe are now starting to take their toll.

Ecobat Technologies, the world’s biggest lead recycler, has this month suspended production at its Paderno and Marcianise plants in Italy, taking out 80,000 tonnes of annual supply.

The move reflects “extreme energy prices and other excessively burdensome costs in Italy, which show no signs of improvement”, the company said.

Glencore is reviewing the sustainability of its lead operations at the Portovesme site, also in Italy, in light of the sustained squeeze on margins. The sister zinc plant was mothballed late last year.

Germany’s Stolberg smelter, meanwhile, remains out of action after being flooded last summer. Repairs are complete but commodities group Trafigura is still awaiting regulatory approval of its purchase of the plant to restart operations.

Stolberg’s extended downtime has cost the European market around 155,000 tonnes of lead supply since its closure a year ago.

Supply-chain tightness has been further aggravated by the European Union’s April import ban on Russian metal. The country exported 127,000 tonnes of refined lead last year with significant flows going to Germany and Turkey.

Global output falling

Lead’s supply problems are not confined to Europe.

Trafigura’s metals arm Nyrstar also operates the Port Pirie lead smelter in Australia, which is poised to close for a 55-day maintenance overhaul.

Chinese lead producers seem to be faring no better. Operating rates at secondary recyclers have averaged only 41% so far this year, down from 55% in 2022, according to Macquarie Bank, citing a combination of reduced scrap supply and power constraints.

Global refined lead output fell by 2.2% over the first seven months of this year, according to the latest monthly assessment from the International Lead and Zinc Study Group.

Usage also fell by almost 1%, meaning the global market was still in a marginal 25,000-tonne supply surplus over January-July but it’s much reduced from the 116,000-tonne production overhang in the year-ago period.

Tight markets

Physical buyers outside of China may struggle to find that surplus.

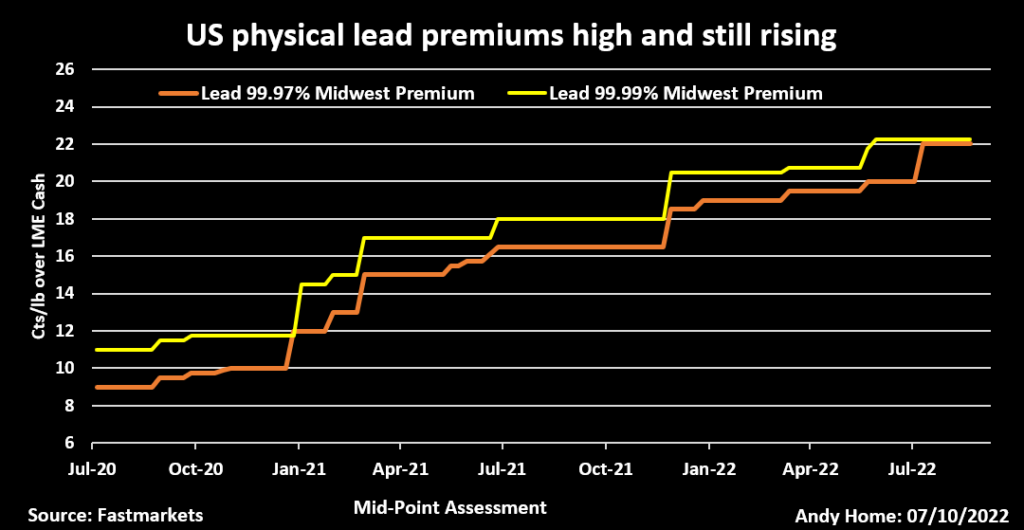

The US market has been super-tight since the unexpected closure of the Florence recycling plant in South Carolina last year.

Midwest physical premiums for high-purity lead surged from 11.75 to a record 20.5 cents per lb over 2021. They have crept higher still since, Fastmarkets assessing the mid-point at 22.25 cents per lb, equivalent to $491 per tonne over the LME cash price.

Indeed, so extreme has been the physical squeeze on metal in the US market that it has been receiving significant tonnages from China for the first time since 2006.

China exported 36,000 tonnes to the United States last year and another 30,000 tonnes in June this year.

That together with stubbornly high physical premiums, suggests there is still little slack in the North American supply chain.

Recession proof

China has also been exporting refined lead to Taiwan, which is the only LME location to have registered any arrivals in recent months

The pipeline, however, looks to be running dry since Chinese exports slowed to just 1,120 tonnes in August, most of it going to Thailand, where there are no LME warehouses.

It’s far from clear how there’s going to be any rebuild in LME warehouse stocks, given reduced flows from China and the multiplying smelter problems outside of China.

Lead is exhibiting the same confused dynamics as sister metal zinc, a darkening macro picture weighing on the outright price even as both physical supply chain and LME market remain tight.

There is one key difference, however, between the two metals. Zinc demand is widely expected to plummet in the coming months as Europe’s manufacturing sector lurches into recession and US growth brakes sharply.

Lead’s main end-use market, by contrast, is vehicle batteries and 78% of that demand comes from replacement batteries.

This makes lead partially recession-proof. Batteries will fail in good times and bad and when they fail not getting a new one is not an option.

Recession may improve availability but not to the same extent as other metals, which suggests that the LME lead market may have to learn to live with super-low stocks for a while yet.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments