Column: Nickel demand boomed in 2021; this year it will be supply

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Global nickel usage surged by an extraordinary 16.2% last year on the back of booming demand from both the dominant stainless steel and fast-growing battery end-use sectors.

The result was a supply shortfall of 168,000 tonnes, the largest production deficit in at least a decade, according to the International Nickel Study Group’s latest statistical snapshot on the market.

The group expects usage to grow another 8.6% this year, exceeding the 3.0 million tonne mark for the first time ever.

However, even that fast rate of expansion won’t match what the INSG expects to happen on the supply side. It is forecasting a massive 18.2% jump in global production driven by Indonesia’s build-out of new capacity.

The prognosis is for a swing back to a modest supply surplus of 67,000 tonnes, although whether that translates into lower prices is a hotly disputed topic.

Demand boom

When the INSG met in April last year it was expecting a strong post-pandemic demand recovery of 9% for 2021.

The bounce-back turned out to be even more spectacular.

Stainless steel is still the largest driver of nickel usage and global output of the alloy rose by 10.6% to 56.3 million tonnes last year, according to the International Stainless Steel Forum.

China, the world’s largest stainless producing nation, experienced a sharp slowdown over the second half of the year resulting in year-on-year growth of only 1.6%.

However, the stainless baton was taken up by the rest of the world with Europe recording its fastest rate of growth since 2010 and output in ex-China Asia jumping 21.2% in 2021.

How long such strength can last is a moot point with Chinese production sliding further in the first months of this year as lockdowns crimp demand for stainless-steel-containing consumer durables.

Fortunately for nickel demand, stainless slowdown will be offset by fast-rising offtake from the electric vehicle (EV) battery sector.

Not all batteries use nickel, particularly in China, but the scale of the EV roll-out is such that demand for the metal is still increasing at a supercharged pace.

Adamas Intelligence estimates that 18,610 tonnes of nickel were deployed onto roads globally in new electric vehicles in March, a 50% increase on March 2021. (“Monthly Battery Raw Materials Deployment”)

Goldman Sachs forecasts nickel usage in the EV battery sector to increase by 62% to 285,000 tonnes this year and by another 26% to 358,000 tonnes in 2023. (“Nickel’s Class Divide”, April 28, 2020)

Wave of supply

Indonesia has positioned itself to be the main beneficiary of this battery boom.

The country has historically been a major supplier of first nickel ore and then nickel pig iron to China’s stainless steel sector.

It is now leveraging its huge nickel reserves to stimulate investment in battery-grade metal, or at least a form of nickel that can then be processed into the sulphate that goes into battery cathodes.

Indonesia mined 34.4% more nickel last year and the country’s output of 1.04 million tonnes accounted for almost 40% of global production. That growth rate is still accelerating – production was up 38.2% in the first two months of 2022, according to the INSG.

The shift from stainless to battery nickel has started showing up in a new stream of exports of intermediate products to China, totalling 55,000 tonnes in the first quarter of this year.

This wave of Indonesian supply has been widely expected even if its exact time-line is still problematic, given many Indonesian operators are using innovative processing routes to convert the country’s low-grade ore to something that can be used by a high-performance lithium-ion battery.

It’s why analysts taking part in Reuters’ most recent base metals poll forecast London Metal Exchange (LME) nickel to slide from the then prevailing price of $33,000 per tonne to an average of $26,800 per tonne in the third quarter.

Surplus or deficit?

The market, as always, has got there first. LME three-month metal is currently trading at $26,200 per tonne, albeit in still constrained conditions after the suspension of the London contract in March.

The price is now almost back to where it was trading before what Russia calls its special military operation in Ukraine caused a melt-up to over $100,000 per tonne.

Continued shipments by Russia’s Norilsk Nickel, which remains unsanctioned, have seen the war’s risk premium unwound.

Most analysts are of the view that the Indonesian production wave will keep the price under pressure.

It all depends, however, on whether what Indonesia produces is sufficient to meet Western demand for battery nickel. The high carbon footprint on Indonesian nickel doesn’t concern the Chinese auto sector but Western EV manufacturers such as Tesla have been much more cautious.

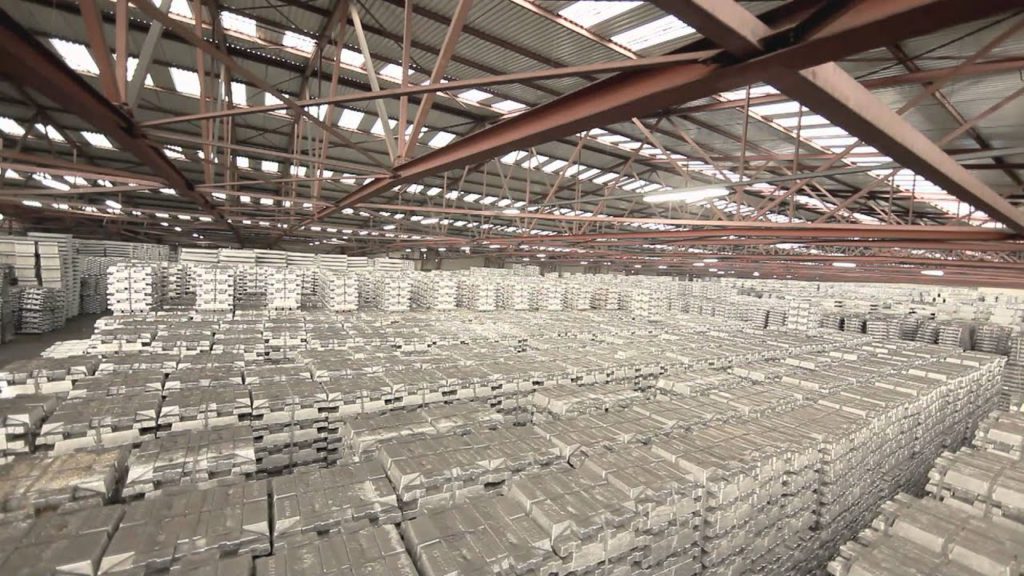

The backdrop to the LME nickel crisis was the clear-out of exchange stocks as buyers snapped up accessible supplies of high-purity Class I nickel, which can be readily converted to nickel sulphate for batteries.

With EV sales rising and nickel demand increasing, not everyone is convinced Indonesian supply will close the gap.

Goldman Sachs concedes that Indonesia will drive a surplus of lower-grade Class II nickel to the tune of 112,000 tonnes this year but forecasts a wider 196,000-tonne deficit of Class I material.

The bank is a bullish outlier in the nickel market with a price target of $42,000 per tonne over a 12-month time-horizon based on a net global supply shortfall of 85,000 tonnes.

Within the context of a three-million-tonne market Goldman’s assessment of market balance isn’t so far from the INSG’s estimate of modest 67,000-tonne surplus.

The devil of the calculation is in the detail as the nickel market continues to evolve into two increasingly distinct streams, one defined by traditional stainless steel usage and one by nickel’s part in the global drive to decarbonise.

Surplus or deficit? In nickel’s current fractured state it could be both this year.

(Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments