Column: New EU power market, same old problems for metals sector

European Union (EU) energy ministers last month struck a deal to reform the bloc’s power market.

The proposed changes to the EU’s “electricity market design” are a response to the spike in European power prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

They will, according to Spain’s Energy Minister Teresa Ribera, mean that “consumers across the EU will be able to benefit from much more stable prices of energy, less dependency on the price of fossil fuels and better protection from future crises”.

But will it be enough to save Europe’s struggling industrial metals production sector?

The brutal reality is that half of the region’s primary aluminum and zinc capacity and almost a third of its silicon capacity is currently offline due to high power prices.

The immediate impact comes with potential future impact as well.

Producers are reluctant to invest in the new metals capacity needed to achieve Europe’s self-sufficiency goals because they can’t model power prices over the time-frame to build a new mine or smelter.

“We need bold action to get out of a dead-end street,” was the stark warning from Bernard Respaut, head of the European Copper Institute (ECI), speaking at a debate on Europe’s power crisis jointly hosted with industry association Eurometaux.

Light-tough reform

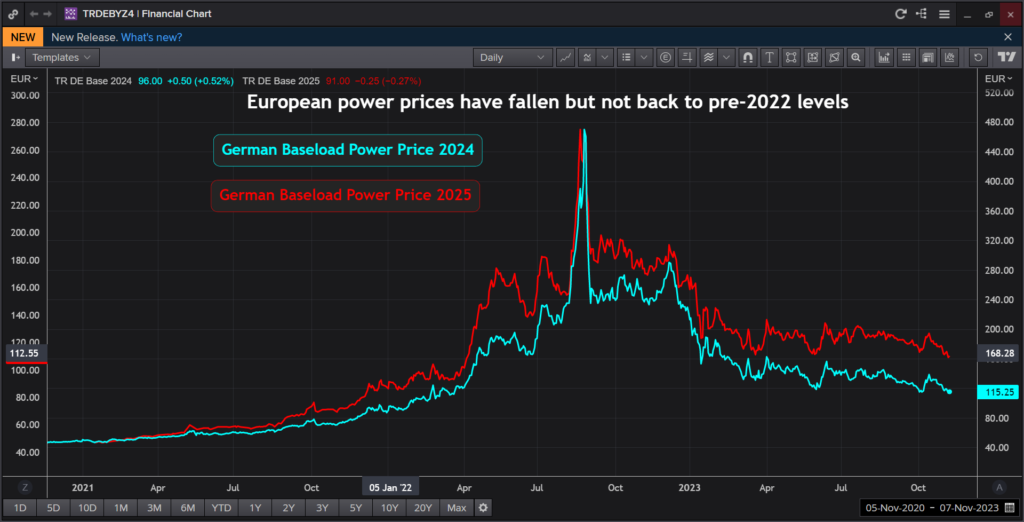

European power prices have fallen a long way from their 2022 peaks, when the region was still reeling from the reduction in Russian gas supplies.

However, they are by no means back to levels trading before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and that isn’t going to change any time soon.

Wholesale pricing will continue to be determined on a pay-as-clear model, where bidding goes from the cheapest to the most expensive source, which tends to be gas. It’s just that it’s now LNG rather than Russian gas that sets the price.

EU member states were deeply split on proposals for more fundamental reform of Europe’s power market to allow for a complete break of the gas-power price linkage.

The hard-won compromise keeps the existing market mechanism, which its supporters claim is more efficient than other models in a liberalized electricity market.

Rather, the focus will be on longer-term price stabilizers such as power purchase agreements (PPA) between generators and users and two-way contracts for difference (CFD) for investment in new green generation.

The PPA problem

US aluminum producer Alcoa is a poster child for Europe’s PPA model, using it to help secure the long-term future of its San Ciprian smelter in Spain.

The company has PPAs with local power suppliers Endesa and Greenalia covering around 75% of the smelter’s base load power when it returns from care and maintenance next year.

Alcoa has the advantage of being in Spain, which has been aggressively building out renewable energy capacity and has Europe’s most developed PPA market.

The country is Europe’s third highest renewable energy generator, much of it solar, and has by far the highest PPA contract capacity at a current 4.2 gigawatts, according to the European Commission. (“The development of renewable energy in the electricity market”, June 2023).

Others are not so fortunate.

“We can’t buy a PPA because it’s not available on the market,” Mats Gustavsson, head of energy at Swedish base metals producer Boliden, told the Eurometaux meeting.

With limited forward liquidity in the company’s local Nordpool power market, “no-one’s willing to take the risk on a fixed-term PPA”, he said.

Even if the local market structure allows for PPAs, many smaller companies struggle to pass the credit tests needed to sign what can be as long as a 10-year contract.

Moreover, many power suppliers will only offer PPAs on a pay-as-produced basis rather than the base-load structure that metal producers would prefer.

The EU reform package is intended to iron out some of these problems by, for example, mandating member states to ensure guarantee schemes for smaller companies looking to enter PPAs.

But it offers neither short-term relief for Europe’s many mothballed production facilities nor the levels of certainty needed to build the next generation of mines and processing plants.

Strategic dialogue

Europe’s focus on the longer-term solution, pivoting towards cheaper renewable energy, leaves untouched the immediate problem of tying spot power pricing to a volatile gas market.

The bloc’s power prices have historically been twice those of the US, but are now three or four times higher.

Metals producers are not only having to adjust to currently high electricity costs, but face even higher costs as they seek their own pathway to net zero.

The danger is that the cost of going green “is going to kill us”, Gustavsson said. Boliden, it’s worth noting, has just shuttered its Tara zinc-lead mine in Ireland at least partly due to high energy costs.

The answer, according to the ECI’s Respaut, is to take a more comprehensive approach to Europe’s industrial base and connect the disparate dots of critical metals production, renewable energy and power pricing.

Europe has to decide which strategic sectors it wants to keep and what it needs to do to help them not just survive but thrive.

And it needs to do so sooner rather than later.

As Respaut concluded: “We need to get to action, because time is running.”

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Jan Harvey)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments