Column: Metal markets brace for a downturn of a different kind

The spectre of recession has hung heavy over this year’s London Metal Exchange (LME) Week festivities.

The analyst consensus is that Europe’s manufacturing sector is already contracting and the United States may well follow.

Demand forecasts have been slashed. The International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG) now expects global zinc usage to contract by 1.9% this year. At its April meeting, it was expecting 1.6% growth.

The International Nickel Study Group has cut its global demand forecast from 8.6% in May to 4.2%, reflecting a slide in stainless steel production.

Large amounts of aluminum are already turning up in LME warehouses as the supply chain destocks.

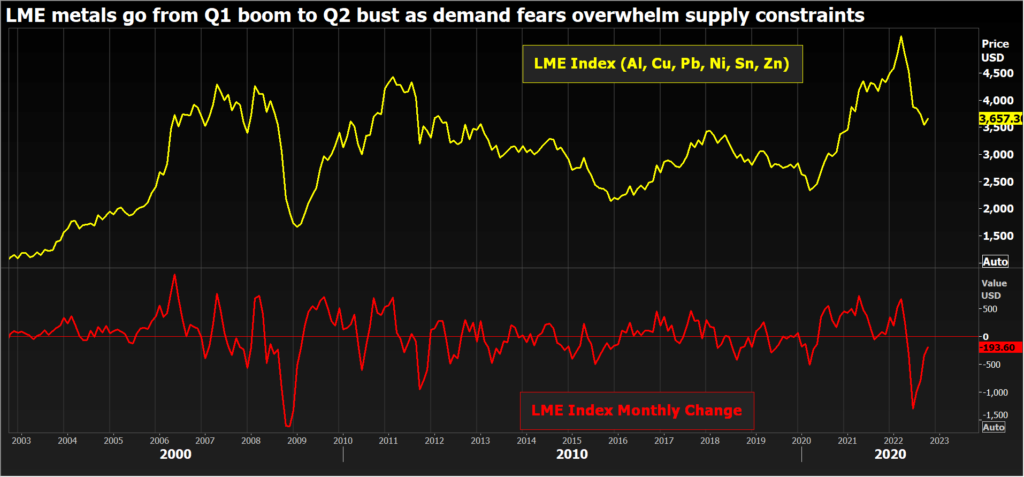

The LME Index, a basket of core base metals, has gone from boom to bust in double-quick time, collapsing by 29% from its all-time highs in March.

But this downturn comes with three unusual characteristics which have combined to create a heady cocktail of uncertainty.

Russian metal – take it or leave it?

The status of Russian metal has been a key talking point at the many seminars and parties this week in London.

Should the LME suspend deliveries of Russian aluminum, copper, and nickel or should it maintain its policy of not preempting official sanctions?

Battle lines are drawn.

German copper producer Aurubis has joined US aluminum producer Alcoa in publicly calling for an LME ban on Russian metal. Norway’s Hydro wants government sanctions.

European aluminum consumers group FACE wants the European Commission to intervene to prevent any ban, saying it would risk “the destruction of the independent downstream European aluminum industry”.

The deadline for responses to the LME’s discussion paper is Friday.

There is a lot of metal supply at stake here. Rusal produces almost four million tonnes of aluminum each year.

Nornickel accounts for around 7% of global nickel supply and, critically for the LME, is a major supplier of the Class I metal deliverable against the exchange’s contract.

Russia produced 920,000 tonnes of refined copper last year, about 3.5% of the world’s total, according to the US Geological Survey.

An LME ban on deliveries of Russian metal would clearly have significant ramifications for both LME and physical market pricing. More government sanctions would make an even harder impact.

Smelter problems, low stocks

The second oddity is that the downturn in pricing is coming at a time when supply in many metals is still very stressed.

Europe has already lost over a million tonnes of aluminum smelting capacity due to high energy prices and it’s likely to lose more as power price hedges expire.

The impact on the aluminum price has been cushioned by the simultaneous downturn in spot demand and an aggressive ramp-up of production in China over the first half of the year.

However, China’s aluminum smelters are facing constraints too, particularly those in the drought-hit hydro province of Yunnan, an emerging hub of “green” metal production.

The smelter bottleneck is most acute in zinc, reflecting both European power-related curtailments and a string of problems at other smelters around the world. Canada’s CEZ has just joined the list, announcing it will close by the end of the month for preemptive cell maintenance. It doesn’t yet know when it will be back.

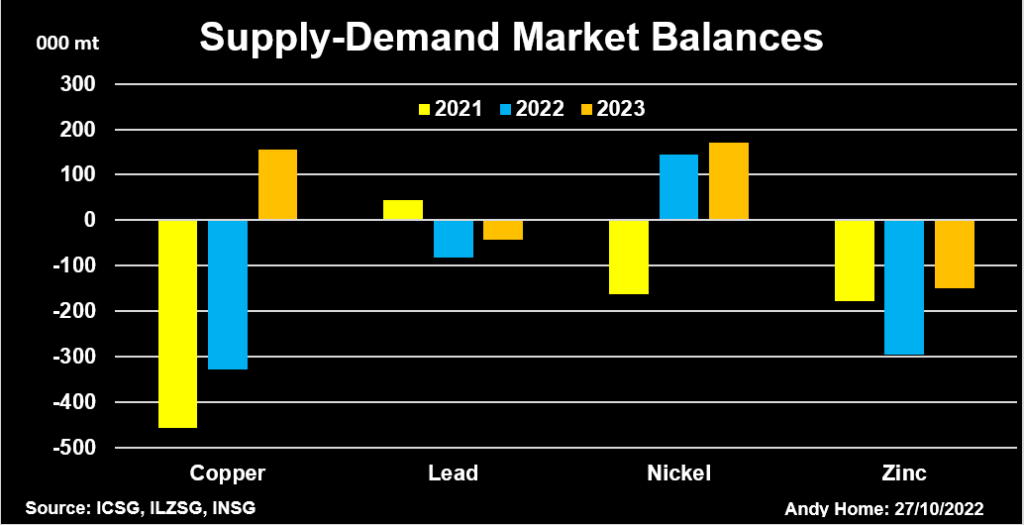

The ILZSG forecasts another year of supply deficit for zinc and lead next year as smelter availability reduces the flow of mined concentrate.

The outlook is for continued high physical premiums, particularly in Europe and North America, and no rebuild in depleted exchange stocks.

Copper is least impacted by the energy crisis and there is broad analyst consensus around The International Copper Study Group’s (ICSG) forecast for the global refined market to move from a supply deficit to a 155,000-tonne surplus next year.

However, the modest scale of that surplus is likely to keep supply tight and, like zinc and lead, will do nothing to replenish depleted visible stocks.

The conundrum of low price and low inventory seems set to continue for a while and it will become more acute if the LME were to restrict the delivery of Russian metal.

Green transition

While its sister organizations downgraded their demand forecasts for lead, nickel, and zinc, the ICSG has actually lifted its demand growth estimate for this year from 1.9% to 2.2%.

China’s strong imports of refined copper this year have boosted the ICSG’s calculation of apparent usage to 2.5%. Imports will likely accelerate further given the drawdown in bonded warehouse stocks and the resulting super-high import premium.

The country’s hunger for copper seems anomalous given the well-flagged problems in the property sector, a major component of Chinese copper demand.

However, it seems that copper usage, in China at least, is now finding an extra driver in the form of government investment in green transition technology.

The much-hyped green booster may finally be starting to arrive and it raises the interesting question of whether Doctor Copper will retain his price relationship with the broader economic cycle or will start to move more in tune with the decarbonization cycle.

This is already happening in nickel. Although usage in electric vehicle batteries is still small relative to that of the stainless steel sector, it’s growing faster and is playing an ever more important role in the global market structure.

The high energy prices that are roiling both metal producers and consumers will accelerate the green transition as Europe looks to reduce its dependency on Russian fossil fuels.

That means even more government funding for renewable generation capacity and for electric vehicles subsidies, bringing forward both the energy transition timetable and the draw on the metals needed to achieve it.

Cloudy outlook

The world is going to need a lot more metal if it is to meet its carbon reduction targets. Unfortunately, current prices are too low to incentivize the necessary investment in new mines and smelter capacity.

It’s a major conundrum that can be added to the puzzling mix of bearish outright pricing, existing supply disruption, potential Russian supply disruption, and, in several cases, critically low exchange inventory.

Confused? Don’t worry. So was just about everyone else in London this week.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Kirsten Donovan)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments