Column: LME stays Russian metal ban with views starkly split

The London Metal Exchange (LME) has announced it will continue accepting Russian metal as good delivery against its industrial metal contracts, for now at least.

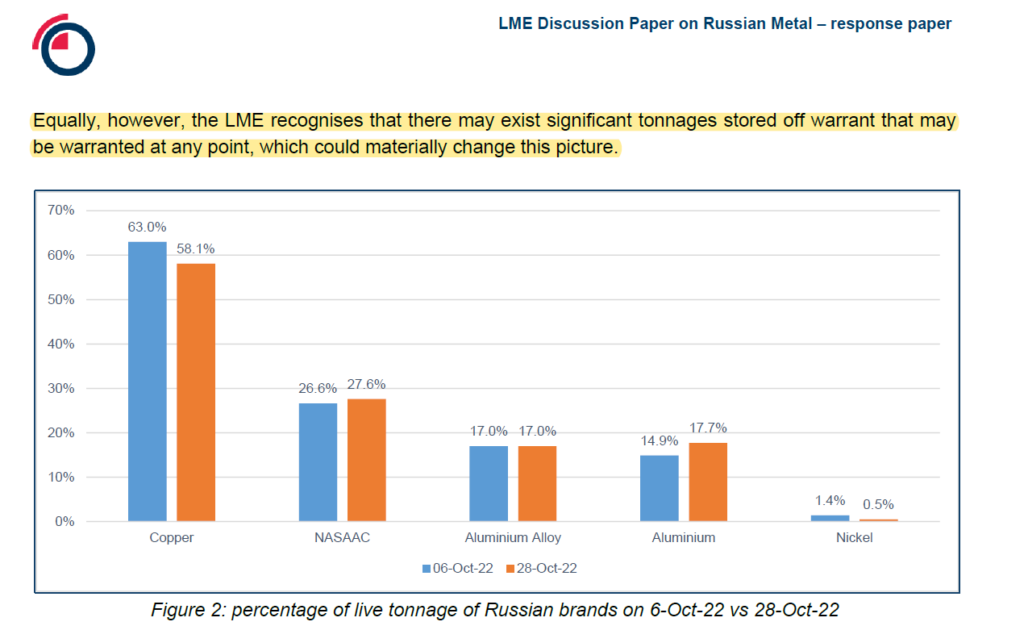

It made the decision knowing “it is likely that additional tonnages of Russian metal will – in time, if not immediately – be warranted in the LME physical network.”

That brings with it the risk of LME pricing moving from a global to a Russian benchmark, creating a disconnect between paper and physical markets.

Absent formal government sanctions against Russian aluminum, copper, and nickel, everything depends on how many players choose not to take Russian metal in their 2023 supply contracts.

Many will self-sanction. But many won’t. The LME’s discussion paper on the acceptability of Russian metal has revealed just how split the global industry is on the question right now.

The stark divisions leave the exchange with little option but to take a wait-and-see approach.

Split down the middle

The LME received 42 written responses to its discussion paper, including 11 from traders and banks and 11 from producers.

Many responded after taking their own soundings of customer intentions next year. Industry associations also joined the debate, meaning feedback came from a broad cross-section of the supply chain.

Opinions were almost split down the middle, with twenty-two wanting no change and seventeen calling for an immediate suspension. Two favored thresholds for Russian metal, an option deemed too complex, and one abstained from making a choice.

North American respondents tended towards the LME taking action, while Asia-based respondents tended towards the status quo. European views were more evenly divided, the LME said.

The two sides of the debate disagree on just about everything, including the critical question of how much self-sanctioning will take place.

“The diversity of views (…) was clear, with respondents from both sides of the debate providing evidence that supported their viewpoint,” the LME noted.

The pro-suspension group claims banks are increasingly loathe to finance Russian metal, a potentially bigger hit on LME liquidity than a consumer boycott. The status-quo group, however, told the LME that “many banks” were still providing financing liquidity.

Suspending Russian brands could significantly harm exchange liquidity, says one side. But not to the same extent as doing nothing, says the other.

There isn’t even a consensus yet on whether Russia constitutes a Conflict-Affected or High-Risk Area under responsible sourcing codes, the LME noted.

Definitely not nickel

Interestingly, the only point of agreement was that the LME shouldn’t under any circumstances suspend Nornickel’s nickel brands.

The company is a major producer of the Class I refined nickel that is deliverable against the LME nickel contract. After the March nickel crisis and the resulting liquidity drain, cutting off Russian metal could “threaten the existence of the contract”, in the words of one respondent.

The situation in the copper market is more nuanced. While Russian metal accounted for 58% of live stocks at the end of October – the highest ratio of any metal – it is clear that up to now it hasn’t been staying around too long.

That’s because copper is leaving LME warehouses almost as soon as it arrives. LME copper stocks have slumped from 145,750 tonnes to 89,975 tonnes over the last four weeks as metal heads for a tight Chinese market.

Rotterdam and Hamburg have been highly active arrival points this year, suggesting shipments from Nornickel’s Arctic port of Dudinka. But even after some heavy inflows over the last two days, copper stocks at the Dutch port are up by just 1,650 tonnes on the start of 2022.

LME inventory patterns show that there are still willing buyers of Russian copper, particularly in China, which remains hungry for the metal in all its forms.

It’s aluminum that poses the real dilemma for the LME. It’s a much bigger market and Russia’s Rusal is a big player with annual production of around four million tonnes.

Aluminum supply is also notoriously slow to adjust to changes in market conditions, meaning lots of it can pile up very quickly.

The process has already started with more than 300,000 tonnes of aluminum, some of it Russian, warranted in LME warehouses over the course of October.

More will come as recession bites in Europe, including Russia itself, and US manufacturing growth brakes sharply.

It’s not certain that China will be a natural buyer, given it’s the world’s largest producer and is itself prone to bursts of over-production.

Premium market

Excessive aluminum stocks have caused the LME problems in the past, most recently in the form of long warehouse load-out queues in the early 2010s. Those drove a warehouse rental wedge between the LME price and the “all-in” price paid by physical users.

It’s a template for how things could play out again if LME aluminum pricing moves to a Londongrad discount.

The market, however, is better equipped to deal with another aluminum price fracture than a decade ago.

Physical premiums can now be traded and hedged on both the LME and its US peer CME Group. The latter’s US Midwest contract is firmly established and has notched up over two million tonnes worth of activity every year since 2017.

The LME acknowledged views suggesting “the market is better structured to manage a lower LME price and higher premiums than it would be to manage a higher LME price and a discount.”

It’s all going to depend on just how much Russian aluminum makes it to LME warehouses and how long it stays. If it sticks, the market of last resort could, to quote one respondent, become the market of “no resort”.

The underlying issue is to what extent the global supply chain will continue accepting Russian metal but it is clear there is no consensus answer yet.

The LME has promised that starting in January it will publish a monthly report on the amount of Russian metal in its storage network.

The new transparency may not sway polarised opinions but it will at least be an important gauge of how metals pricing, particularly aluminum pricing, evolves next year.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Kirsten Donovan)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments