Column: Copper mine supply wave arrives but will it be the last?

A wave of new copper mine supply is washing through the market, with smelters reaping the benefits in higher treatment and refining charges (TCRCs).

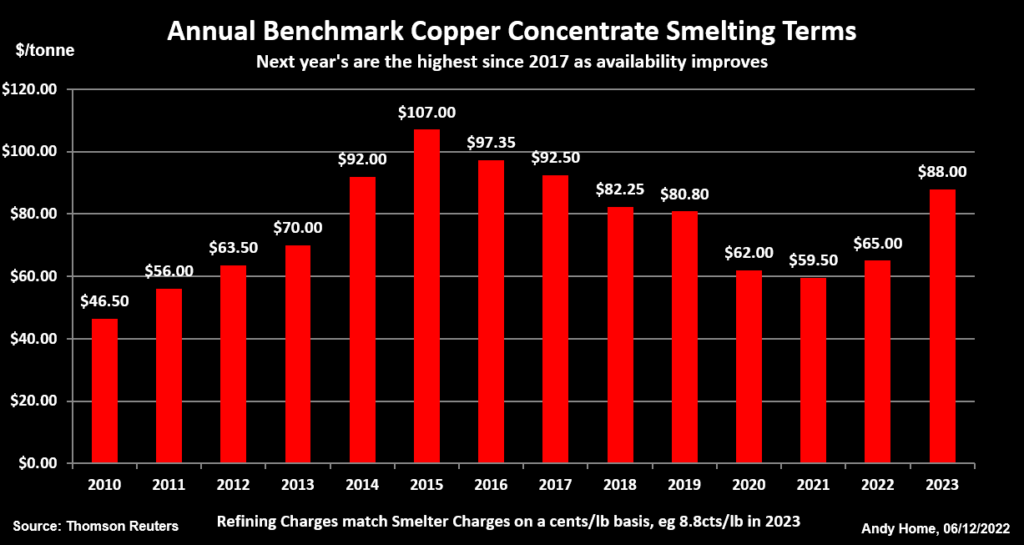

Next year’s benchmark terms, negotiated by Freeport McMoRan and Chinese smelters, will be $88 per tonne and 8.8 cents per lb, up 35% on this year and the highest annual charges since 2017.

Smelter charges for converting mined concentrate to refined metal offer a mirror on what is happening at the raw materials stage of the copper supply chain, rising during times of surplus and falling during times of deficit.

The jump in the 2023 benchmark signals a step-change in mined output after years of low or no growth and one which, many analysts argue, will keep a lid on prices as the concentrates surge feeds through to the refined metal market.

However, once this wave of new production breaks, what comes afterwards? Not nearly enough, according to Glencore, which is warning of a 50-million-tonne supply shortfall by 2030.

New mines, old problems

Only two major copper mines were brought on stream between 2017 and 2021, according to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG).

Four big supply additions are now arriving almost simultaneously. The Kamoa Kakula mine in the Congo and the Quellaveco mine in Peru are both greenfield projects and currently ramping up.

In Chile, the Quebrada Blanca II and Spence-SGO mines are boosting output as they switch from oxide to sulphide ores.

The ICSG estimates world copper mine production expanded by 3.5% in the first nine months of this year, compared with a modest 1.9% expansion over the course of 2021.

Its October forecast was for full-year growth of 3.9%, a downgrade from its May forecast of 5.1% growth reflecting a slew of production misses by many of the sector’s top operators.

Chile, the world’s largest producer, has experienced a particularly high disruption rate this year, output sliding by 6.7% year-on-year in January-September, according to the ICSG.

Peru managed growth of only 1.4% over the same period with output still 5.0% below pre-covid levels in 2019.

Miners are suffering multiple operating headwinds and the scale of collective disruption is partly offsetting the extra tonnage from new mines.

However, mine production growth this year will still be stronger than the last few years. Moreover, what is not produced for whatever reason in 2022 will be deferred into 2023, when the ICSG expects the world’s copper mines to produce 5.3% more metal.

[Click here for an interactive chart of copper prices]

The benchmark TCRCs for next year’s shipments capture the trend towards a growing surplus of mined concentrate.

Smelter bottle-neck

The impact of improved supply on treatment charges has been accentuated by a series of smelter shutdowns, both planned and unplanned, in South America and Europe this year.

While mined production was up by 3.5% in January-September, refined copper production growth lagged at 2.3%, according to the latest ICSG estimates.

The Group is expecting an acceleration to 3.3% next year but that’s still behind the forecast rise in mine production.

Smelters have their own problems, particularly the rising cost of energy, and are warning that treatment charges will have to stay higher for longer if they are to build more processing capacity.

“It would be good to have some incentive from the mining side to increase capacity and invest in our primary smelting sites,” Roland Harings, chief executive officer at Europe’s biggest copper smelter Aurubis, told delegates at last month’s CRU World Copper Conference Asia in Singapore.

But if new smelting capacity is built, will there be enough copper concentrates to feed it?

Empty horizon

Not according to Glencore.

“Whatever was planned to be built has been built,” Chief Executive Gary Nagle told analysts on the company’s investor day conference call.

Those are the projects now ramping up into production but, he warned, “there is nothing coming behind”.

Glencore estimates that if the world is going to meet its net zero emissions targets, it will be cumulatively short of copper to the tune of fifty million tonnes by 2030 as the global pivot towards green energy transition boosts copper usage in grid upgrades, solar panels and electric vehicles.

New mines can’t be built and commissioned that fast, even if the will is there. The sector’s low capital expenditures on expanding production suggests many are still loath to commit to the mega-billion investments needed for the next generation of supply.

Glencore says it can raise its copper production by around 60% to 1.6 million tonnes per year through relatively low-cost brownfield expansions.

It won’t do so until the expected deficit becomes tangible in the form of higher copper prices. “We don’t want to promise tonnes to a market that is not absolutely screaming for the extra additional volumes,” Nagle said.

The company is also working on the greenfield El Pachon mine project in Argentina, but that would represent what Nagle termed “the last taxi on the rank” in a world crying out for more mine supply.

Glencore has skin in the game when it comes to talking up copper’s price prospects, but there is broad concern among analysts about the lack of investment in the next generation of copper mines.

Smelters can surf the current wave of new supply for at least another year and quite possibly into 2024 if the level of disruption moves down a gear or two next year.

Copper’s problem is the lack of visibility on where the next wave is coming from. Right now the horizon looks disconcertingly empty.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Alexander Smith)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments