Column: Base metals start the new year with depleted inventory

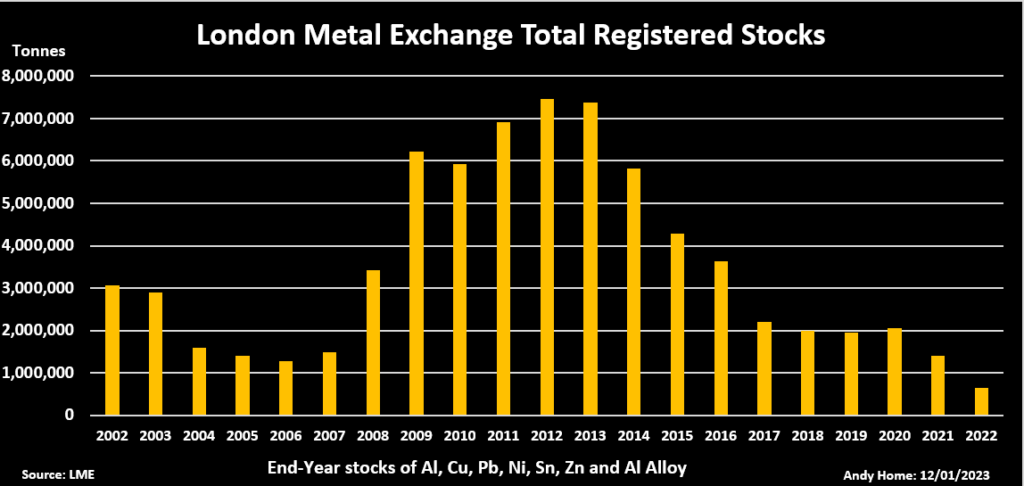

The London Metal Exchange’s (LME) global warehouse network held 654,345 tonnes of metal at the end of December, less than half the tonnage registered at the close of 2021.

It’s the lowest end-year inventory in the system this century and reflects two years of steady withdrawals which have left exchange stocks of metals such as zinc and lead almost depleted.

There has been a mirror drawdown of what the LME calls off-warrant stocks, meaning metal that is being stored off-market but with the option of exchange warranting.

LME warehouse operators have slashed storage capacity by 15% over the last 12 months as ever less metal rests with the market of last resort.

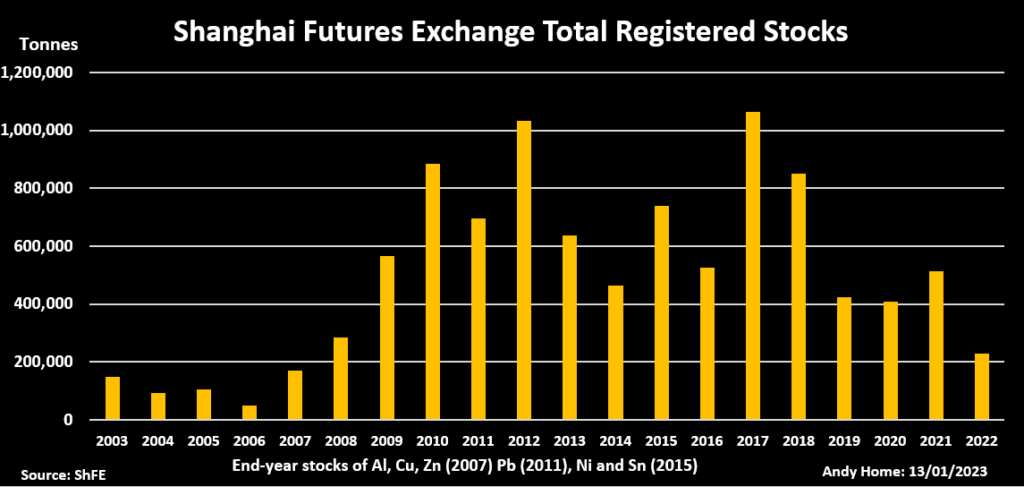

This is not just an LME phenomenon. Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) warehouse stocks also ended the year at their lowest level since 2007.

Exchange inventories are just one component of the bigger inventory picture but can have an outsize impact on price, particularly time-spreads. It’s no coincidence that all the LME base metals have experienced bouts of extreme tightness over the last couple of years.

The turbulence is likely to continue until there is a sustained rebuild in inventory back to historical norms.

Going, going…

Registered stocks of all the LME base metals fell last year with the single exception of tin, which rose by a modest 950 tonnes to 2,995 tonnes. It’s still a very low stocks level relative to the past and represents just a couple of days’ worth of global consumption.

Copper stocks ended the year flat at a bombed-out 88,550 tonnes, an early-year rebuild having gone into reverse over the second half of 2022.

Registered nickel stocks fell by 45% year-on-year, aluminum stocks by 52%, lead by 54% and zinc by 85%.

Even the low headline figure of 654,345 tonnes at the end of December flatters to deceive. Around 45% of that tonnage was awaiting physical load-out, leaving live stocks at just 357,000 tonnes.

Off-warrant stocks have also collapsed over the last couple of years. They totalled 239,386 tonnes at the end of November, down from 1,879,261 tonnes at the end of 2020.

Most of the remaining shadow inventory is aluminum. It accounted for 189,000 tonnes at the end of November, just about all of it at Asian locations, which continue to see rotation of metal between on-exchange and shadow stocks as financiers play the storage-spreads game.

The only other significant shadow stocks at the end of November were the 34,000 tonnes of zinc in Singapore. This metal, so far at least, has failed to make its way onto LME warrant and there’s no guarantee it will do.

Physical competition

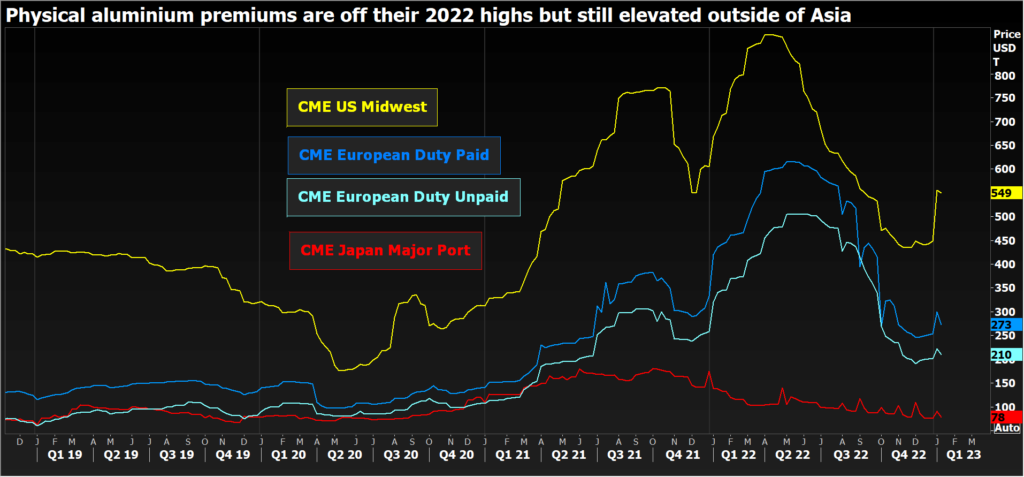

The LME is competing for metal with a physical supply chain that has been severely dislocated first by covid-19 and then by Europe’s energy crisis.

Metal users in Western markets have been prepared to pay eye-watering premiums to fill gaps in their intake books.

Zinc smelter closures in Europe, for example, mean that a tonne of refined zinc can fetch $500 over and above the LME cash price. The LME contract is in backwardation but the cash premium over three-month metal is a relatively modest $20 per tonne.

Spare zinc units are more valuable in the physical supply chain than in the terminal market. That’s going to remain the case going forwards with Fastmarkets reporting that annual 2023 premiums are settling close to spot assessments, almost double last year’s level.

The same is true of the other base metals.

Aluminum premiums peaked in the second quarter of last year but a tonne of ingot can still command a premium of around $550 over LME cash in the US Midwest and of over $200 in Europe.

Only in Asia is the physical premium low enough at around $80 per tonne to allow LME warehousers to compete for new inventory.

Everywhere else, high physical premiums for all metals are proving sticky, maintaining the incentive to divert spare units from exchange delivery.

That’s not to say there hasn’t been gaming of LME inventories at times over the past couple of years, but the games are predicated on there not being much spare metal around for LME delivery in the first place.

Chinese exports

Total registered stocks in the ShFE warehouse network stood at 228,797 tonnes at the end of December, down from 512,368 tonnes at the close of 2021.

It was the lowest end-year total since 2007, although the comparison isn’t exact because ShFE only traded aluminum, copper and zinc at the time. Lead was added in 2011 and both tin and nickel in 2015.

Aluminum stocks registered the biggest year-on-year fall at 70%, the headline figure falling below the 100,000-tonne level in December for the first time since 2016. Zinc stocks were down by 65% and lead stocks down by 59% on December 2021.

It’s worth noting that significant quantities of all three metals have left China over the last year to capitalize on high Western premiums.

Exports of primary aluminum were 195,000 tonnes in the first 11 months of 2022, the highest flow since 2009. Zinc exports over the same period were 80,000 tonnes, the highest since 2015, and lead exports of 100,000 tonnes were the highest since 2007.

Seasonal rebuild

ShFE stocks have started 2023 on a surge ahead of the approaching Lunar New Year.

This is a seasonal phenomenon as end-users wind down operations for what is the most important holiday period in the Chinese calendar. This year’s stocks rebuild may be accentuated by the messy exit from the country’s zero-covid policy.

But it is taking place from a particularly low base and, if the past is any guide, will go into reverse once China’s manufacturing sector reopens for business.

LME stocks could desperately do with any sort of rebuild, whether seasonal or cyclical. European recession should in theory mean more metal becoming available for exchange delivery and there remains the possibility of unwanted Russian metal turning up in the system.

So far, however, significant arrivals remain conspicuous by their absence and until that changes, low visible inventory is going to keep roiling the LME base metals.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments