Column: Collapsing metal inventories clash with plunging prices

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

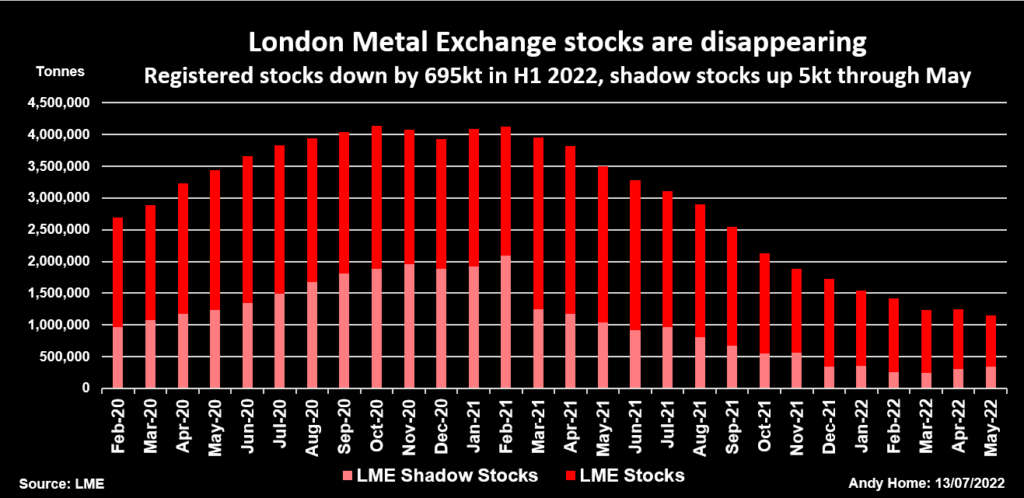

London Metal Exchange (LME) stocks are rapidly dwindling.

LME warehouses held just 696,109 tonnes of registered metal at the end of June, the lowest amount this century.

Inventory halved over the first six months of the year and June’s tally was down by 1.67 million tonnes year-on-year.

The downtrend has further to run.

Nearly 306,000 tonnes of metal were awaiting physical load-out at the end of last month. Available tonnage of all metals was just 390,280.

LME shadow stocks, metal stored off-market with the option of exchange delivery, rebuilt modestly in April and May but the year-to-date increase has been a negligible 4,600 tonnes.

Shrinking exchange stocks should be a bullish price signal. Right now, however, macro is trumping micro as Western recession fears pummel the industrial metals complex. The LME Index .LMEX, which tracks the performance of the exchange’s six main base metals, has slumped by 31% from its April peak.

The scale of the disconnect between price and stocks is striking. The resulting mismatch of current scarcity and expected future surplus is likely to be resolved by sporadic flare-ups in LME time-spreads.

Stocked out

This is currently happening in the LME zinc market. The cash premium over three-month metal flexed out to $218 per tonne last month. After loosening over the end of June it expanded again to more than $100 per tonne on Tuesday.

Available live stocks shrunk to a depleted 14,975 tonnes at one stage in June and are still a meagre 22,475 tonnes.

The rest of the headline zinc inventory of 82,200 tonnes is scheduled to depart.

It also happened to sister metal lead last year, when the cash premium spiked to over $200 per tonne in August as LME on-warrant stocks fell to less than 40,000 tonnes.

Time-spread tightness has been a recurring feature of the LME lead contract ever since and the cash premium is once again edging wider, ending Tuesday valued at $33 per tonne.

That’s because lead stocks haven’t rebuilt in any meaningful way, currently totalling 39,250 tonnes with available tonnage at 34,850.

The LME tin market has been living with depleted stocks since the start of 2021 and backwardation appears to be now hard-wired into short-dated spreads.

Physical tightness

Low LME stocks of all three metals reflect extreme physical supply-chain tightness.

All three have seen significant supply disruption over the last year with tin smelters hit by coronarivus lockdowns, zinc smelters in Europe powering down due to high energy prices and the Stolberg lead plant in Germany out of action since July 2021 due to flooding.

Physical premiums for all three metals have hit record highs in Europe and the United States and remain close to those levels even as outright prices have dropped like a stone.

The LME has acted as market of last resort for physical buyers and stocks will only rebuild once the supply-chain pressures pass.

Chinese exports are helping rebalance both lead and zinc markets but the process is a slow one as freight and logistics bottlenecks brake arbitrage flows.

Copper’s muted rebuild

Copper was stocked out last October, when live LME tonnage fell to 14,150 tonnes and the cash premium exploded to an eye-watering $1,000 per tonne.

The LME intervened with lending caps and deferred delivery options, a tool-kit now extended to all its physically-deliverable contracts after the March nickel debacle.

LME registered copper inventory recovered to a May peak of 180,925 tonnes but the trend has since reversed. Headline stocks have fallen back to 130,975 tonnes with fresh deliveries being offset by a string of cancellations as metal is turned around for the exit door.

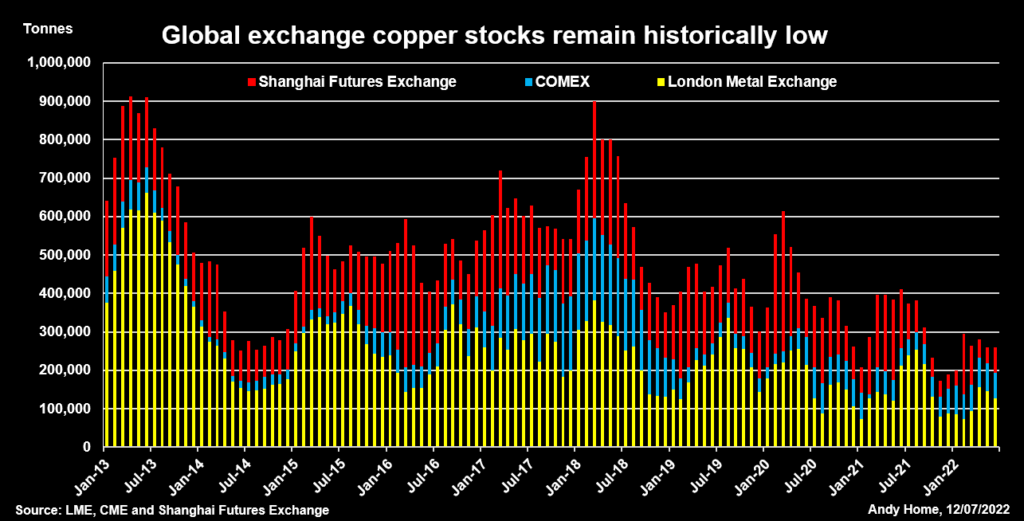

Indeed, combined inventory across all three major copper trading venues – LME, CME and the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE)- totalled 261,000 tonnes at the end of June, up 71,000 tonnes on the start of January but down by 150,000 tonnes on June 2021.

It’s a muted rebuild considering the world’s largest buyer – China – spent much of the first half of the year constrained by rolling lockdowns.

Off-market build?

Weaker Chinese demand doesn’t appear to have made any impact on ShFE copper inventory, which remains low at 69,000 tonnes, down from 129,500 tonnes a year ago.

However, the headline stocks may be deceiving.

The Chinese market has been rocked by another multi-pledging stocks scandal reminiscent of the Qingdao fraud of 2014.

That seems to have triggered movement of both aluminum and zinc into safe-haven storage and may be deterring copper exchange deliveries.

It’s quite possible that such rotation between visible and non-visible storage is accentuating the LME stocks downtrend as well.

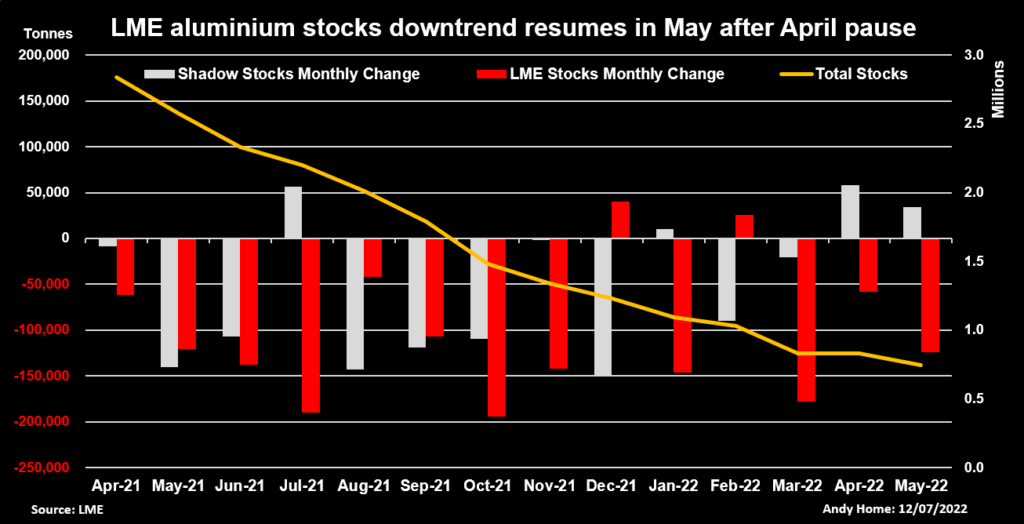

Registered aluminium stocks, for example, collapsed by 64% over the first half of the year. Live tonnage stands at just 156,300 tonnes.

Yet there is no sign of tension in aluminum time-spreads, the cash-to-three-months period trading in mild contango.

The market seems to be assuming that there is no shortage of aluminum despite the headline stocks figure ticking lower every day.

But if metal is available, it is evidently sitting in the statistical darkness.

One small clue as to its existence was a 92,000-tonne build in LME shadow aluminum stocks over the course of April and May.

Such metal is primed for LME warranting if price and spreads move into the right alignment and the recent rise suggests that some metal at least is being enticed back to the paper market from the physical market.

Regional imbalance

Just about all of the shadow aluminum stocks build has occurred in Asia, which accounted for 87% of the 289,978 tonnes in this category at the end of May.

LME warehouse locations in Europe held just 21,642 tonnes and US ones 14,608 tonnes.

The same regional skew is clear to see across all the LME base metals and is as equally true of registered stocks as it is of shadow inventory.

It is a symptom of the supply and freight issues that have roiled the metals markets since the onset of covid-19 two years ago.

It is also a warning that metals supply chains are still far from functioning efficiently, even as prices bow to the weight of macro selling.

(Editing by Kirsten Donovan)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments