Chinese nickel billionaire boosts Australian miner in Indonesia

A little-known Australian company is becoming the Western face of a Chinese nickel behemoth.

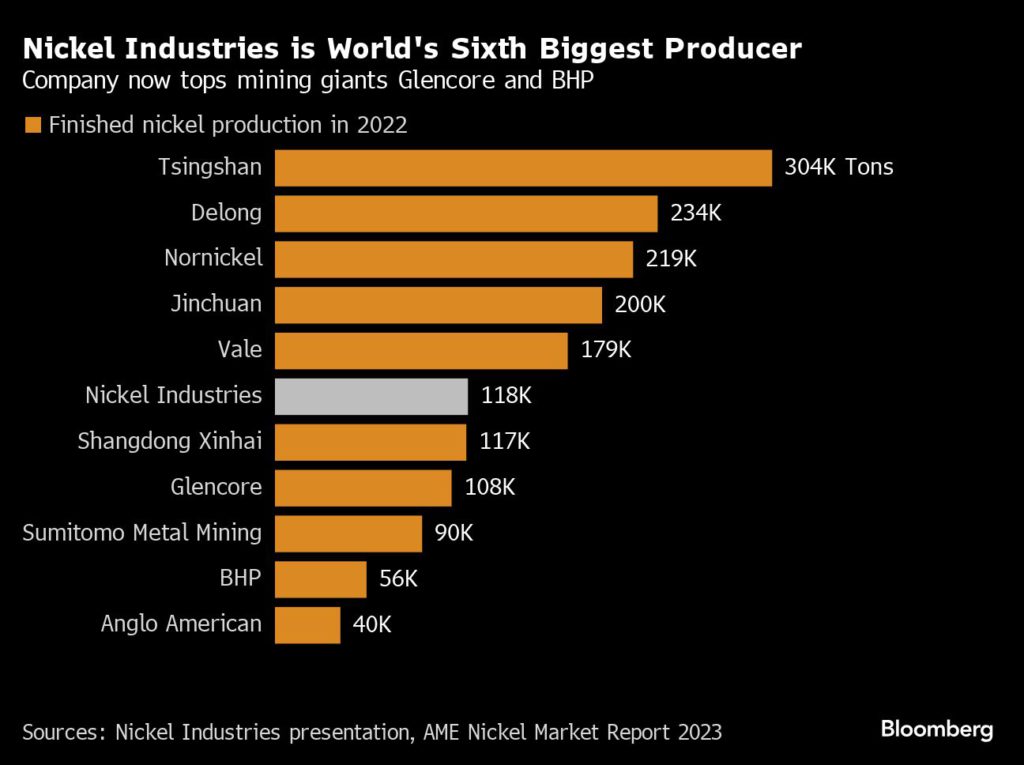

In under a decade, Nickel Industries Ltd. has gone from a relatively small miner to the world’s sixth-biggest producer of a metal used in products from batteries to stainless steel. Riding a Chinese-led boom in Indonesia’s nickel sector, it owns or has stakes in five plants in the country that churn out more of the commodity than household names like BHP Group Ltd.

Behind the company’s success is Tsingshan Holding Group Co., the world’s largest nickel and stainless steelmaker and Nickel Industries’s biggest shareholder. The closely-held conglomerate owned by billionaire Xiang Guangda has built smelters for the Australian company at a speed and cost that’s given it an advantage over competitors, but which could also pose risks for the firm going forward.

In return, Nickel Industries has given Tsingshan — which is heavily dependent on the Chinese market — access to Western investors, a means to recycle the capital it has poured into Indonesia and a potential back door to the US electric vehicle market.

“They realize that they have to be able to sell into other markets,” said Angela Durrant, principal base metals analyst at consultancy CRU Group. “They want to be able to say it’s not just a Chinese product that’s coming out.”

Officials at Tsingshan didn’t respond to a request for comments.

For Nickel Industries, the tie-up is a double-edged sword. While Chinese firms led by Tsingshan dominate nickel processing in Indonesia, winning a reputation for building and operating plants at an extremely low cost, some Western corporations and investors are wary of becoming dependent on them.

Beyond the geopolitical tensions between Beijing and Washington, many firms still see Indonesia, which accounts for more than half of global nickel output, as a risky place to invest. That’s due in part to a history of foreign investors losing control of assets or being hit by export bans for raw commodities — a feature of departing President Joko Widodo’s administration.

There are also concerns about the widespread use of coal, environmental damage caused by mining and deadly industrial accidents that have raised questions about the sector’s shortcuts.

“There’s been skepticism because we’ve got the double whammy of being in Indonesia with a Chinese partner,” Nickel Industries’ chief executive officer Justin Werner said in an interview last month.

But without Tsingshan, Nickel Industries would not exist in its current form. The Sydney-based firm began its life in Indonesia mining what was then a remote nickel deposit on Sulawesi, east of Borneo, but was forced to stop operations when the government banned the export of raw ore in 2014 to bolster its domestic smelting industry.

At the time, Tsingshan was firing up some of its first Indonesian nickel smelters just a few miles away but was having difficulty buying stakes in nearby mines, according to a person close to the company. The Chinese giant started to purchase the Australian firm’s ore — before taking a 20% stake for $26 million in 2018.

“That was really the genesis of the relationship,” Werner said. “It wasn’t our great planning, just coincidence.”

Nickel Industries used those funds and others to buy a 25% interest in two nickel smelting lines that Tsingshan was building in Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park, known as IMIP, on the island of Sulawesi. The purpose-built site, the brainchild of Xiang, would eventually come to symbolize Indonesia’s nickel boom — the good and the bad.

Known in Chinese commodity circles as “Big Shot” for his high-risk tolerance, Xiang rose to broader prominence in 2022 for nearly breaking the London Metal Exchange after being squeezed out of a large bearish bet on nickel prices.

But arguably his boldest move was in Indonesia. Since arriving 15 years ago, Tsingshan has spearheaded a more than $30 billion wave of Chinese investment in the country’s nickel smelting sector. That effort has centered on huge industrial parks like IMIP, which have help Indonesian exports surge, and the construction of high-pressure acid leach plants that produce a form of nickel coveted by the battery sector.

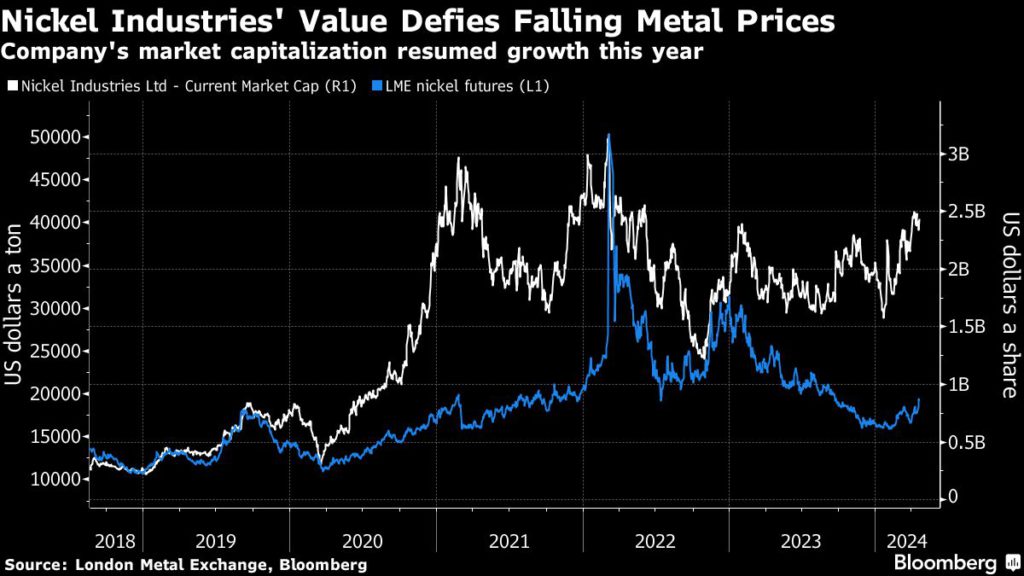

The production boost triggered a plunge in nickel prices last year, forcing some miners in other countries to weigh shutting for good. But thanks to economies of scale alongside cheap labor and coal, smelters within parks like IMIP have kept running.

Those include four plants now majority-owned by Nickel Industries that were built by Tsingshan. The conglomerate has used the Australian firm to diversify the investors involved in the industrial park and reduce its concentration of risk there, according to a person familiar with its thinking, while retaining influence by holding 23% of the company’s shares.

“It is a one-sided relationship in a way but I think it’s what they have to do to operate in Indonesia,” CRU analyst Durrant said.

And while the Chinese tie-up has been a blessing for Nickel Industries so far, there’s clear downside risk. Since its founding, IMIP has been the site of a number of industrial accidents.

A fire at a Tsingshan-owned nickel-processing facility there in December killed 21 people and prompted the government to demand that China improve its smelting operations in the country. That incident remains under investigation.

US market access

Tsingshan’s involvement is also a potential hurdle to Nickel Industries’s access to a rapidly growing market: the US. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act offers generous subsidies to EVs, provided they contain a limited proportion of components originating from Chinese firms.

The rules around joint ventures remain unclear, and Nickel Industries’s product could still fall on the wrong side of the legislation. CEO Werner said he hopes a new high pressure acid leach plant can help change that when it comes on line next year, after which Tsingshan will sell some of its stake to a new investor to meet IRA requirements.

The building of the HPAL — by Tsingshan — has only just begun. There isn’t even a paved road to the site. But after almost a decade in partnership with the Chinese firm, Werner signaled confidence.

“Everything the Chinese have said they’d do, they’ve delivered,” he said.

(By Eddie Spence and Alfred Cang)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments