China’s metals imports boomed in 2021, so did its exports

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

China imported a record amount of primary and alloy aluminum in 2021, the world’s largest producer tapping the international market for the second consecutive year.

Imports of refined nickel doubled year-on-year and the country continued to step up purchases of a widening range of nickel raw materials.

Refined copper imports dropped from the previous year’s record highs but remained robust with flows of “scrap” accelerating after a relaxation of purity thresholds.

But 2021 was a year of two-way flow in China’s trade with the global metals market.

Exports of both refined lead and tin surged to multi-year highs as supply shortfall in Western markets forced open the arbitrage window between Shanghai and London prices.

Such divergence in China’s refined metal trade patterns is highly unusual but reflects the equally unusual combination of pandemic recovery and supply-side constraints.

Here are some key takeaways.

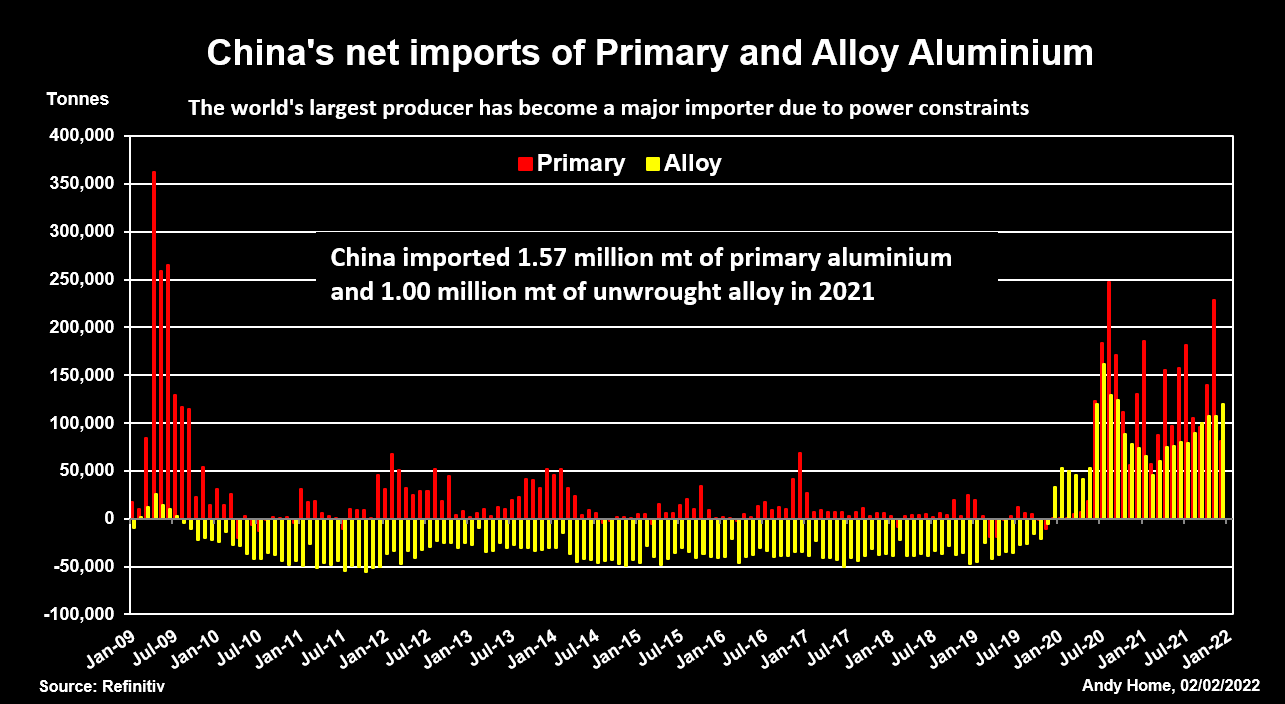

Aluminum – new import record

China’s net imports of unwrought primary aluminum reached 1.57 million tonnes and those of unwrought alloy 1.00 million tonnes last year.

Volumes were up by 24% in 2020 and eclipsed the 1.43 million tonnes imported in 2009, the only historical precedent for the world’s largest producer needing more aluminum in such quantities.

That, however, was a global financial crisis one-off. Two consecutive years of high imports speak to the structural supply pressures in the domestic market caused by power-related production curtailments.

Indian metal accounted for 54%, or 855,000 tonnes, of last year’s primary imports. Malaysia was the largest supplier of alloy, shipping 321,000 tonnes. The country has become a major recycling and processing hub, a shift in global “scrap” flows that has generated a step-change in China’s imports of alloy.

China is sucking in more primary aluminum but it is also exporting more semi-manufactured products. Shipments were up by 18% last year with December’s exports of 553,000 tonnes an all-time monthly record.

The spread of power curtailments to Western smelters and the resulting tightening in availability could well accentuate this trade anomaly.

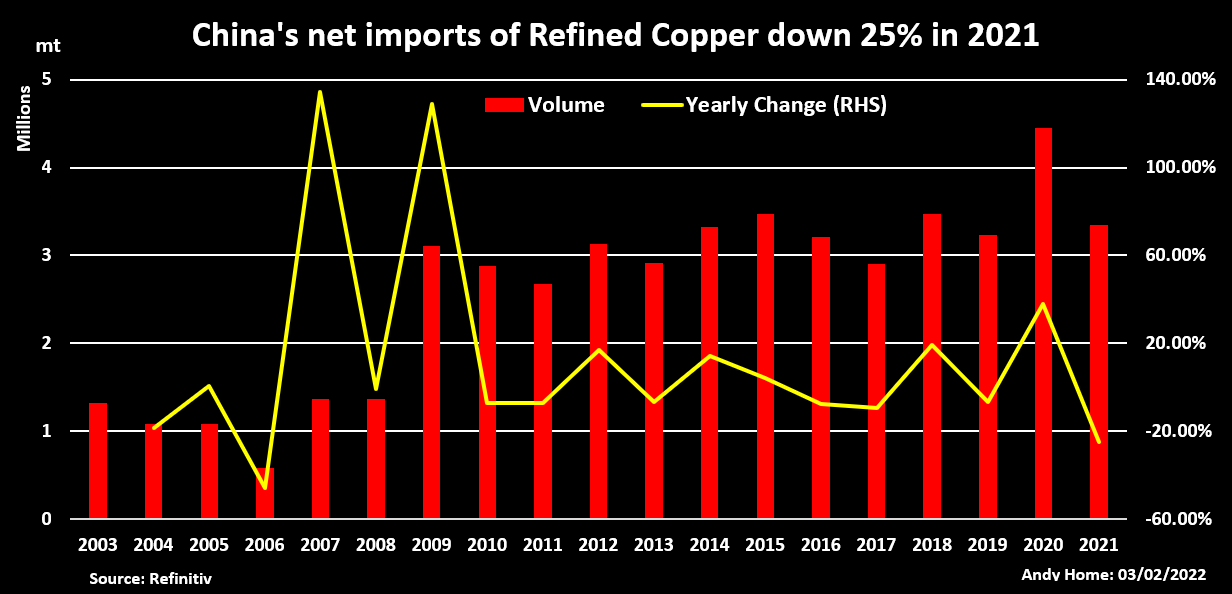

Copper – still hungry

China’s import dependency has defined the copper market this century and last year was no exception.

Refined copper imports fell by 25% to 3.3 million tonnes relative to 2020 but the previous year had shattered the record books. Last year’s tally was actually up marginally in 2019.

The decline in refined metal imports must also be seen in the context of “scrap” imports.

These slumped from over three million tonnes in 2017 to just 944,000 tonnes in 2020 as China tightened purity rules. A last-minute policy change has reopened the door to higher-grade recyclable material and imports jumped 80% to 1.7 million tonnes in 2021.

Just as a shortfall of secondary copper meant more appetite for the refined metal in 2020, last year’s import wave of recyclables would have dampened that demand.

Nickel in all forms

China’s imports of refined nickel doubled to 261,000 tonnes with a marked acceleration over the second half of last year.

Tightness in the battery-grade nickel supply chain is driving the surge in imports of so-called Class I metal, which in turn is feeding through to low stocks and flaring time-spreads on the London Metal Exchange.

The strengthening demand pull from the electric vehicle sector is also evident from fast-growing imports of nickel sulfate, a chemical precursor for battery manufacture. Volumes mushroomed from 5,600 tonnes in 2020 to 44,700 in 2021.

China also imported more ore, matte, intermediate product and more ferronickel last year, attesting to its huge appetite for nickel at every stage of the process chain.

Zinc – sliding imports

China’s net imports of refined zinc slid by 16% to 429,000 tonnes last year, the lowest annual tally since 2016.

This multi-year trend has reflected the build-out of domestic smelter capacity – production hit a fresh record high of 6.56 million tonnes in 2021 – but it appreciably accelerated in the fourth quarter of last year.

December’s imports of 10,334 tonnes were the lowest monthly total since 2008 and reflect shifting physical market dynamics. The London-Shanghai arbitrage is moving in favor of exports as smelter closures in Europe open up supply-chain gaps and send premiums soaring.

There is no sign yet of the export gates opening but that may change. There is a precedent in lead, zinc’s sister metal.

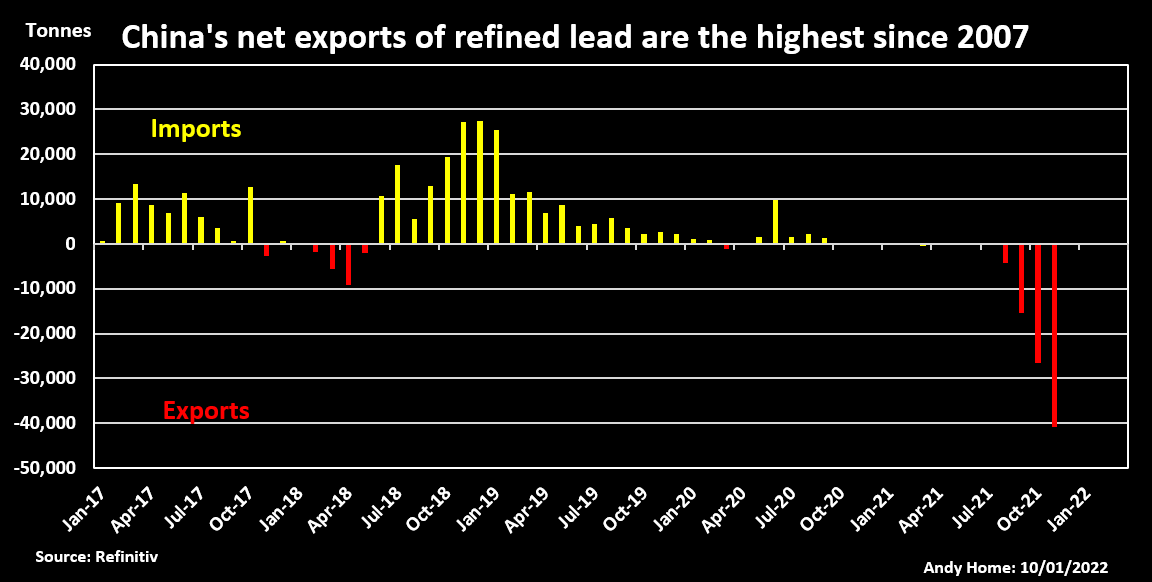

Lead – highest exports since 2007

China exported 95,000 tonnes of refined lead last year, the highest annual total since 2007, which was the year when Beijing imposed an export tax on refined lead, since then outbound flows have been understandably muted.

That all changed in 2021, however, as China shipped surplus to a deficit Western market characterized by historically high physical premiums and extreme time-spread tightness on the LME.

Export volumes grew over the second half of the year with shipments heading as far afield as the United States (37,000 tonnes in October and November) and the Netherlands (11,000 tonnes in November).

There is the potential for more export flows, given continued low LME stocks and persistent high physical premiums.

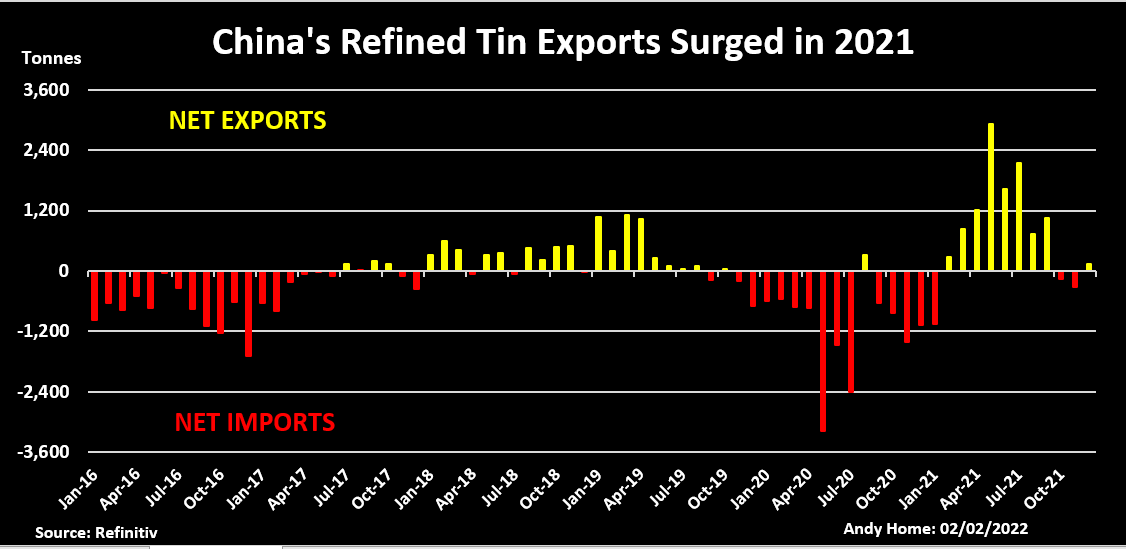

Tin – China to the rescue

The Western tin market was even tighter than lead last year with super-high LME cash prices and physical premiums.

China came to the rescue of beleaguered buyers everywhere else. Exports of 14,320 tonnes were also the highest since 2007, some of them even making their way to Europe, which attests to the scale and extent of the squeeze on physical availability.

China had been a significant importer in 2020 to the tune of 13,200 tonnes, which made last year’s flip to net exporter all the more dramatic.

More flip-flop is possible with imports growing again over the fourth quarter of 2021. Both China and the rest of the world seem to be struggling to secure enough of the soldering metal, China’s trade patterns fluctuating according to who needs tin most at any one time.

(Editing by Emelia Sithole-Matarise)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments