China’s maxed-out aluminum industry eyes future in Indonesia

China’s aluminum producers are following in the footsteps of their nickel peers by setting up smelters in Indonesia.

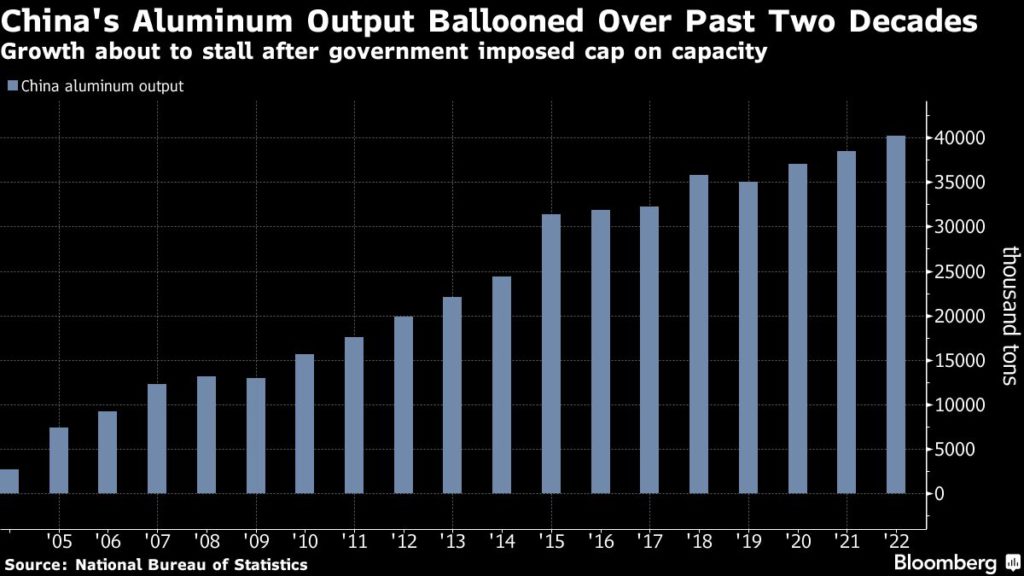

After two decades of rapid growth, China’s aluminum sector is bumping up against a domestic capacity ceiling imposed by President Xi Jinping’s government. At the same time, Indonesia wants to do for aluminum something like what it’s done with its nickel: stop exporting raw ore and get foreign investors to build smelters.

Over the past decade, China has successfully tapped into Indonesia’s vast nickel resources, turning the country into a hub for producing the metal that’s critical for electric-vehicle batteries and stainless steel. They’ve built refineries, smelters, and even a nickel museum on Indonesian islands.

One new Chinese-backed aluminum plant is already up and running in the Southeast Asian nation, with backers including Tsingshan Group Holding Co. — the firm that spearheaded China’s rush to spend billions of dollars to develop Indonesia’s nickel story.

“Chinese aluminum companies have to go out of China if they want to expand given the capacity ceiling,” Wan Ling, an analyst at CRU Group, said by phone from Beijing.

Top producer

China accounts for more than half of global aluminum output after breakneck growth this century to feed its urbanization. But the expansion is coming to a halt with the industry set to reach an annual maximum capacity of 45 million tons, imposed by Beijing to prevent oversupply and get rid of older, more inefficient plants.

Meanwhile, Indonesia — Southeast Asia’s largest economy — has been trying to wean itself off exports of raw commodities by forcing producers to do processing and manufacturing onshore. An export ban on its rich deposits of bauxite, the primary ore for aluminum, just took effect this month.

Chinese companies already operate alumina refineries in Indonesia, an intermediate step where bauxite gets processed into the intermediate product.

Now, the first Chinese-owned smelter outside China started up on Indonesia’s Sulawesi island in May, a joint venture between Huafon Group, a chemicals producer, and Tsingshan. It aims for 2 million tons of capacity eventually.

Shandong Nanshan Aluminum Co., one of China’s top makers of the metal, is planning to complete a 250,000 ton smelter by 2026 on Bintan island. China’s top metals-industry association reckons that Chinese companies have tentative plans for 10 million tons of annual capacity in Southeast Asia — mainly in Indonesia.

Carbon footprint

Still, analysts are generally cautious on the potential for Indonesia to become a major hub for the aluminum industry in the same way that it has become for nickel.

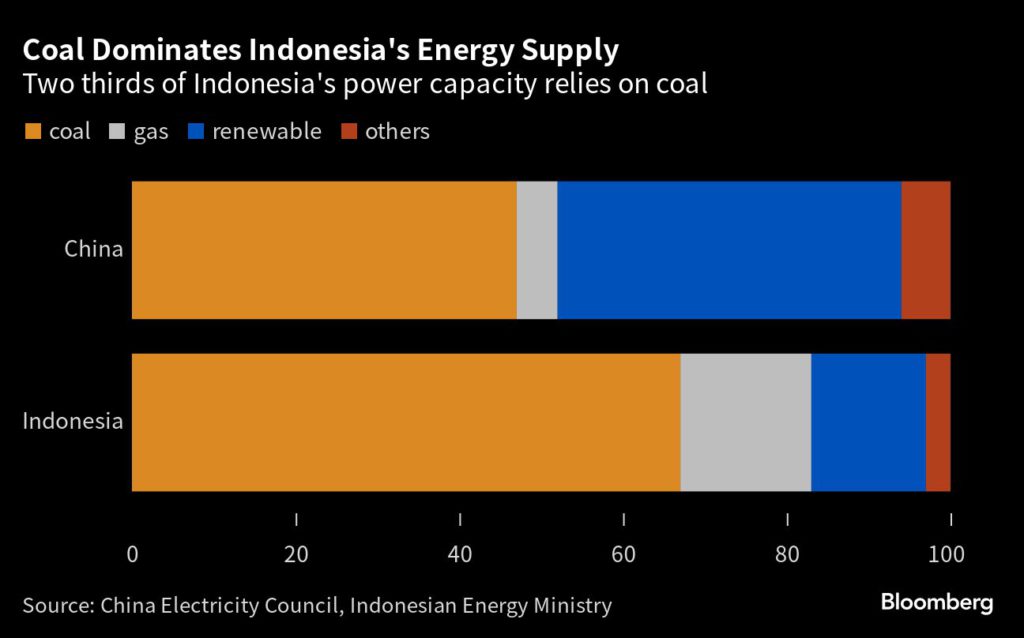

First, Indonesian smelters will be reliant on coal-fired power. That contrasts with global moves — including in China itself — toward greater reliance on renewable energy to feed the industry.

“The biggest challenge will be the coal-fired power supply, which is dominant in Indonesia and has heavy emissions,” said Wang Yanchen, an analyst at Shanghai Metals Market. The projects might eventually face difficulties selling their aluminum as the rest of the world moves toward green metal.

For example, the European Union will introduce a mechanism that charges import duties based on a product’s carbon footprint by 2026. Other jurisdictions such as the US and UK are likely to follow suit.

‘Different story’

Making aluminum accounts for about 4% of China’s carbon emissions, but most new capacity in recent years has been built in provinces, such as Yunnan or Sichuan, where power comes from hydro-electricity plants. Already about 19% of China’s aluminum capacity is hydro-powered, according to researcher Beijing Antaike Development Co.

Second, Indonesia’s nickel boom was partly motivated by the prospect of a demand boom in coming decades, especially from batteries. Aluminum doesn’t have similar demand drivers.

And third, China is structurally much more dependent on Indonesian imports for its nickel needs than it is for aluminum. Chinese companies invested in Indonesia to make sure they had nickel supplies as Indonesia moved to ban ore exports last decade. Indonesia supplied only 15% of China’s imported bauxite last year, meaning the ban is less consequential.

“It’s a different story from nickel,” said Zhu Yi, a Bloomberg Intelligence analyst. “Future output for aluminum won’t be exploding.”

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments