China’s grip on rare earths undercuts projects from US to Japan

A couple hours outside Houston, in a remote field near a Dow Chemical Co. plant, America’s bid to undercut China’s grip on the global supply of rare earth minerals critical to high technology has yet to break ground.

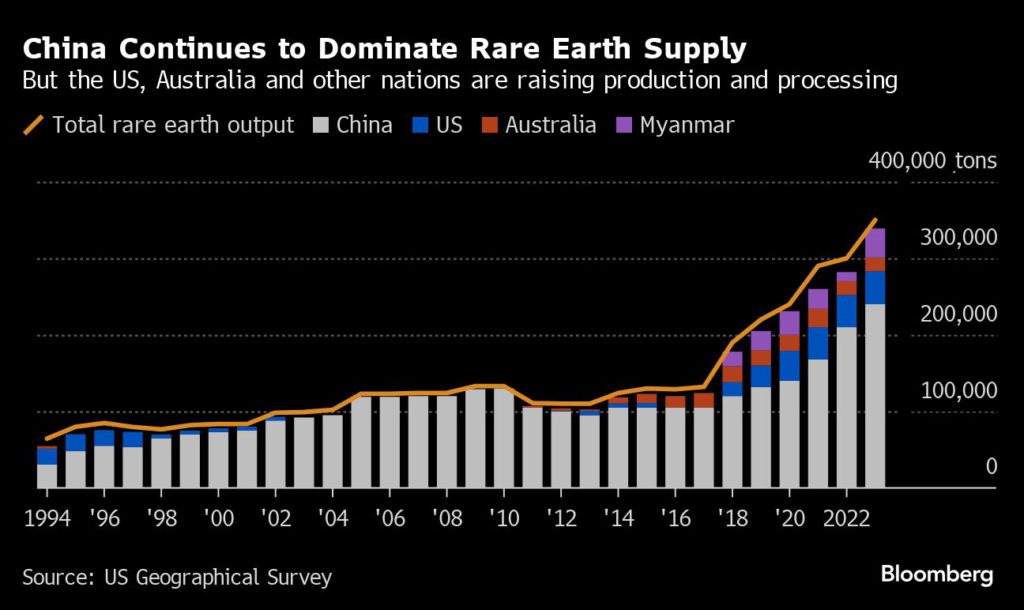

Even when it does, China’s dominance of the market — it controls about 70% of output and more than 90% of refining — means that goal will likely remain out of reach.

The Texas plant, to be built by Australia-based Lynas Rare Earths Ltd., represents a fraction of billions of dollars in subsidies and loans promised for the production and refining of the minerals in the US and its key allies. For the 149-acre (60 hectares) site, Lynas won more than $300 million in Pentagon contracts. If all goes to plan, it will be operating a plant to process rare earths there in two years.

But while national security is a primary driver of the programs in the US and elsewhere, a slump in prices since 2022 is undermining the business case for those projects. That’s raising questions about whether this and similar efforts can develop into a supply chain to rival Chinese firms protected by their government.

“These market conditions have now destroyed most of the hoped-for projects from just a couple years back,” said James Litinsky, the CEO of MP Materials Corp., which owns the only rare earths mine in the US and is building a factory to manufacture magnets in Texas.

“Despite the efforts and investments of many governments, Chinese control over the vast majority of the supply chain remains,” Litinsky said on an earnings call last month.

The metals the US and allies are focused on aren’t actually “rare” but seldom exist in high enough concentrations to justify the often environmentally-hazardous mining. They include 17 chemically-related elements that have properties useful for making electronics in products from phones to fighter jets more efficient.

Laura Taylor-Kale, the assistant secretary of defense for industrial base policy, promised earlier this year that the US will have a “sustainable mine-to-magnet supply chain capable of supporting all US defense requirements by 2027.” She said that once the Lynas project in Texas is operating, the company “will produce approximately 25% of the world’s supply of rare earth element oxides.”

In recent years, the global price slump has been driven by increased supply from China and elsewhere, as well as the weakening Chinese economy, which has meant that domestic industry can’t absorb the higher output.

China’s Ministry of Natural Resources and its industry ministry didn’t respond to requests to explain their reason for raising mining quotas for rare earths in 2023 and 2024, which analysts says helped drive down prices.

“Most rare earths mines are struggling to break even under low prices while early-stage projects face delays and funding shortfalls,” according to a Sept. 3 report in Benchmark Source. Those factors are “potentially slowing the West’s push to reduce dependence on Chinese supply chains,” it added.

Some projects are already reporting setbacks.

Arafura Rare Earths Ltd. is one firm which looks to be struggling to ramp up as planned. It secured an A$840 million ($560 million) Australian government loan this year, with the company raising more capital in July and saying that the project is ready to start construction.

It signed offtake agreements with two Korean auto firms in 2022 for production from its Nolans project north of Alice Springs, Australia, but hasn’t started building.

“We’ve got the debt, we’ve got the approvals, the offtakes are largely in place,” said CEO Darryl Cuzzubbo. “The one missing piece is the equity. We are pushing to get that by the end of the year — that would allow us to start construction first thing next year.”

Cuzzubbo said his goal is to get half the equity from “cornerstone investors, which is tracking very well,” adding that “once we’ve got that, we will then go to the rest of the market for the remaining 50%.”

Iluka Resources Ltd. is another firm confronting multiplying hurdles as it invests in rare earths production in Australia. The company was the recipient of a A$1.25 billion loan in 2022 to develop Australia’s first integrated rare earths refinery, which it aimed to open in 2026. But this year it announced the project could cost as much as A$1.8 billion, well above initial estimates.

Earlier this year, the firm’s chief executive officer accused China of trying to manipulate prices and take control of the industry in Australia.

“China’s influence over the global rare earths market is pervasive,” CEO Tom O’Leary said in May. “It is this monopolistic production, combined with interference in pricing, that is resulting in market failure.”

Lessons from Japan

It was a similar experience that started Japan on the road to reduce its dependence on China for rare earths more than a decade ago. The results show that these projects take longer and are more expensive than initially expected.

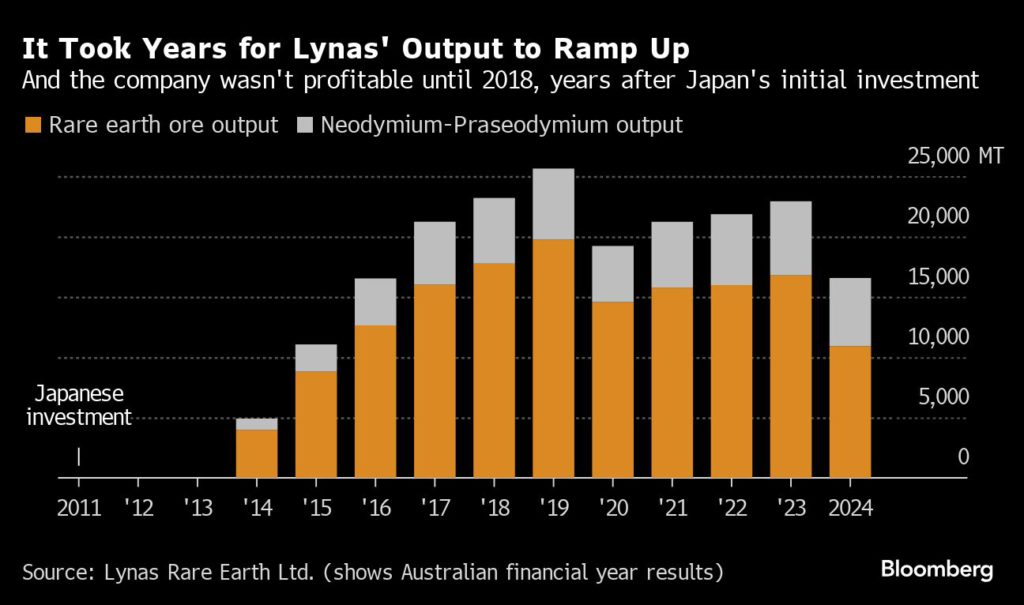

Tokyo invested in Lynas in 2011 with a $250 million investment after Beijing temporarily cut off supplies over a territorial dispute. It took two years before trial production began and even longer to ramp up to forecast levels, according to company statements. The firm didn’t turn a profit until 2018.

It was support from Japan’s companies and the government that helped keep Lynas afloat, CEO Amanda Lacaze said in an interview. Japan backed Lynas by “putting some money in for capital and investment and development of our assets, but also then supporting us through a period of very, very low pricing,” she said.

Japan eventually cut its dependence on Chinese rare earth supplies to around 60% from 80%-90%, former Economic Security Minister Takayuki Kobayashi said in an interview.

However, even more critical was patience, Lacaze said. That was underscored by a company announcement last month: An issue with wastewater permits means that earthworks planned for the Texas facility this year are unlikely to happen, Lynas said in its latest earnings report.

“Patient capital in mining and also in an area where you’re doing something for the first time is really important,” Lacaze said in August. “If we truly want an industry, we do have to recognize that we’re playing a 30-year catch-up game.”

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments