China’s copper plants consider cuts after years of breakneck growth

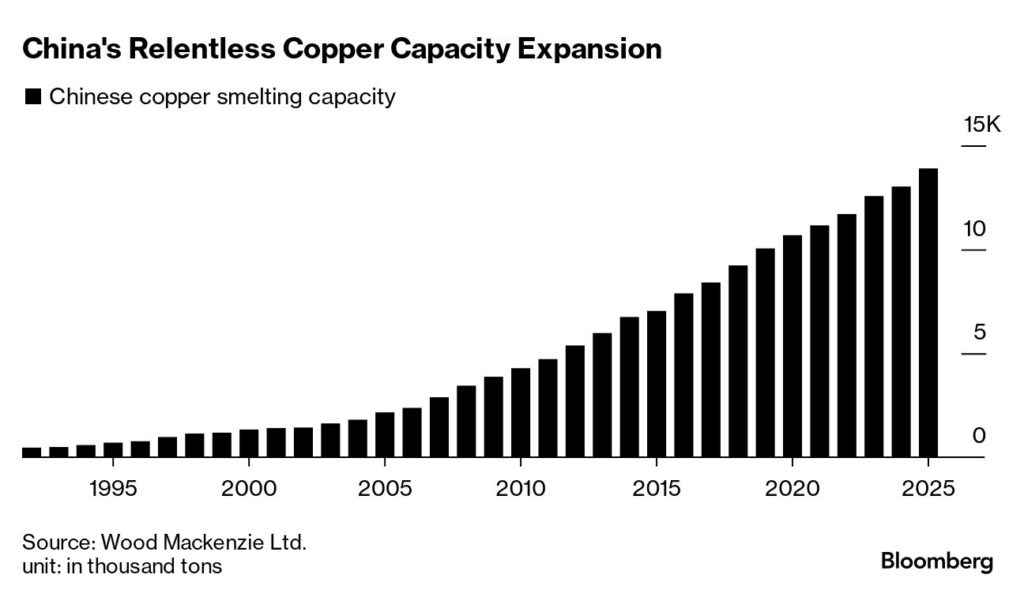

Years of relentless growth are finally catching up with China’s copper smelters.

Stung by disappearing profits, the country’s top industry body last week put forward a menu of options to limit oversupply, from bringing forward maintenance work to postponing new plants or even cutting production outright. The alarm bells are ringing following a collapse in the fees that processors charge miners because there’s not enough ore to go around.

Those fees have plunged to a record low of $21.90 a ton on a spot basis after global curtailments at mines, most consequentially the shuttering of First Quantum Minerals Ltd.’s giant Cobre project in Panama. A lot of that supply was bound for Chinese smelters, which process over half the world’s copper concentrate into refined metal, and which now have a lot more time on their hands.

“The Panama shutdown caught everyone off guard,” said Wang Yingying, an analyst with Galaxy Futures Co. It caused panic in the market and traders are now hoarding supplies, she said.

Smelters have cut output in the past when margins have shrunk. They’ve also turned to using more scrap to replace concentrate. But there’s been little impact on capacity growth, which has been unrelenting. In any case, smelter profits are a side issue compared to the other implication of the collapsing fees: the global shortage of copper may be arriving sooner than expected.

ANZ Banking Group Ltd. sees growing risks around the supply of the refined metal, which is used in everything from electronics to power transmission and solar panels. The bank predicts prices may rise nearly 4% to $8,800 a ton by the end of this quarter, according to a note on Friday.

For all of its manufacturing successes, Beijing has largely been incapable of preventing the kind of blind expansions that quickly lead to overcapacity. That’s been true of smokestack industries such as steel, and it’s true now for drivers of the new economy like solar. The copper sector has been favored with a particularly light touch because of Beijing’s desire to lock-up supply of a metal deemed vital to the energy transition.

Local government

Expectations that the government will have to curb copper capacity in the future, if only to meet its own emissions targets, have accelerated the construction of new plants, as firms push expansion to the limit to capture market share before their window is closed by the authorities. Local governments, meanwhile, have encouraged building more smelters to raise tax receipts, promote employment and meet Beijing’s growth targets.

The collapse in fees “should signal imminent closures of Chinese smelters, but their battle for market share could override the hunt for profit,” according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

And so the construction of new Chinese smelters rolls on, albeit at a slower pace. Capacity expanded by 868,000 tons last year to 12.6 million tons and will rise another 457,000 tons in 2024, compared with an average addition of 658,000 tons over the previous five years, according to Wood Mackenzie Ltd. That spells more competition for global rivals, which may not enjoy the same state tolerance for overcapacity.

It also means that Chinese smelters are more likely to choose softer options for scaling back supply, for example by bringing forward annual maintenance instead of conducting wide-ranging cuts at major plants. Pressure from local governments to keep up economic growth is also likely to be brought to bear.

Ultimately, though, the sector could be forced to concentrate operations in the hands of the most profitable and efficient firms. Smelters on long-term contracts have seen their fees drop 9% from the previous year to $80 a ton, and few are betting against further declines as the copper market tightens.

“The shortage of copper concentrate could drive horizontal consolidation of Chinese smelters,” said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Michelle Leung.

Copper fell as much as 0.4% to $8,452.50 a ton on the London Metal Exchange Monday, before trading at $8,458 by 11:15 a.m. in Shanghai, down for a fourth day as investors trimed bets on a Federal Reserve interest-rate cut.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments