China’s bulging commodity stockpiles show depth of economic woes

Inventories of key raw materials are piling up in China, evidence that economic activity remains too feeble to clear a surplus that’s crushing prices from steel to soybeans.

The government’s growth target for the year looks increasingly out of reach, an unwelcome development for the drillers, miners and farmers that supply the world’s biggest importer of commodities. The blowout in stockpiles might suggest that some traders were caught out by the economy’s poor performance since the end of the pandemic. Others may have underestimated the extent of China’s pivot from the old economy to the new.

But the stockpiling is also testimony to the premium placed by Beijing on making sure its factories and citizens never run short. Even when its economy is hot, China houses outsized quantities of raw materials. It holds more than 90% of the world’s visible copper inventories, nearly a quarter of the world’s crude oil, and over half of staple crops like corn and wheat, according to research from JPMorgan Chase & Co.

So, while consumption and industrial activity are surely weak, China’s state-owned importers may be not be too fussed if they’ve mistimed their purchases, given their mission to guarantee that the country’s reserves are sufficient come what may.

Coal pile

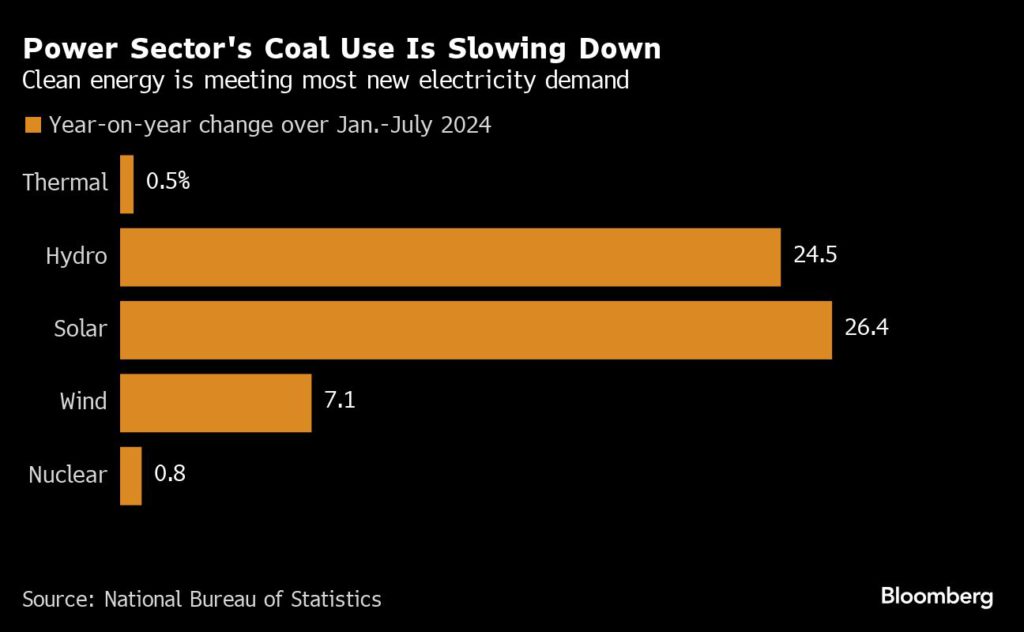

The power-shortage scares of 2021 and 2022 drew renewed scrutiny of China’s energy security, especially around the availability of its mainstay fuel — coal. Beijing’s response was to lift production and imports to record levels.

But those efforts have coincided with subdued industrial demand, and a dramatic surge in clean energy generation that now meets almost all of the country’s growth in consumption. The upshot is that coal inventories rose to a unprecedented 635 million tons at the end of June, from less than 90 million in late 2021, according to an estimate from data provider China Coal Resource.

Crude balance

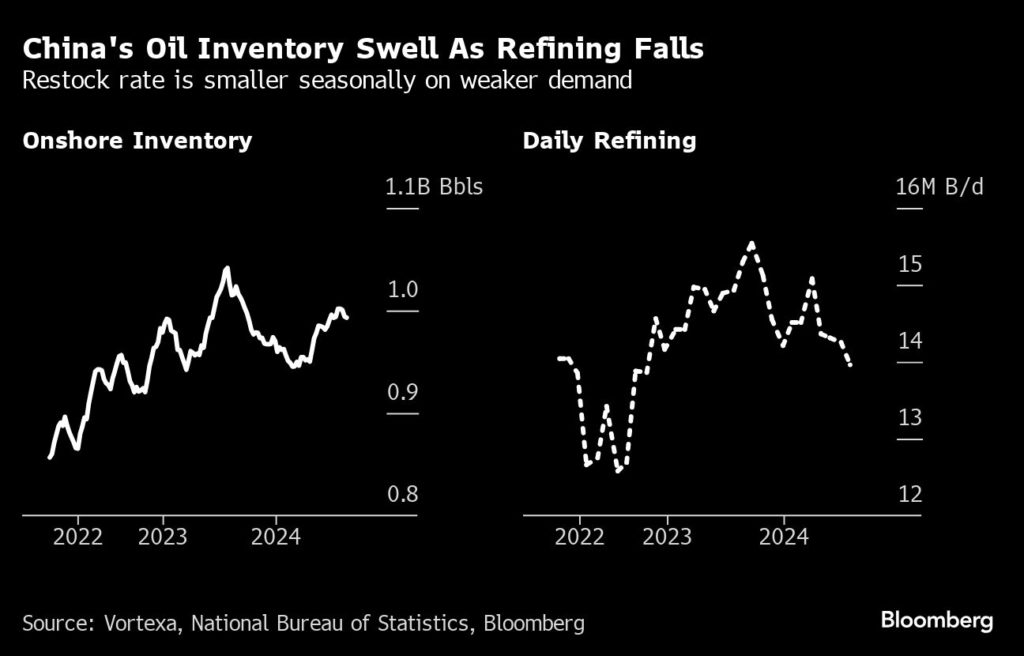

China’s oil market is facing similar issues with a weak economy, rising domestic production, and a long-term decline in demand as decarbonization gathers pace. Refiners have been forced to cut their cloth accordingly by reducing operating rates. Imports have dwindled.

Although onshore crude inventories swelled to a 10-month high of more than 1 billion barrels in July, they’re still below last year’s summer peak, according to Vortexa Ltd. That could signal even fewer imports if firms are taking a cautious approach by drawing on ample supplies to meet any seasonal upturn in demand in the fall.

“Given the uncertain demand outlook, refineries may choose to destock commercial tanks rather than increase buying, if they need to raise runs as demand picks up seasonally,” said Jianan Sun, an analyst at Energy Aspects Ltd.

Iron ore balloons

China’s steel industry is in crisis as the country’s moribund property sector drags on construction demand. Port inventories of its key raw material, iron ore, have ballooned to their highest ever for the time of year.

Margins on fashioning hot-rolled coil, used for car bodies and appliances, are near a record low, although there are tentative signs the market is recovering from its summer slump. But for mills to weather the downturn, they’ll probably have to keep cutting production, and that’ll mean even less demand for the steel-making ingredient.

Copper’s credentials

It’s not all doom and gloom in China’s metals industry. Copper buyers have been lured back to the market by a rapid retreat in international prices from their all-time high in May. That’s showing up in inventories at warehouses tracked by the Shanghai Futures Exchange, which have eased from the four-year high hit in June, although they’re still at a record for this time of year.

Like steel, copper consumption is heavily reliant on the construction industry. But the highly conductive metal has other uses outside the old economy that suggest demand will boom, as China adds more power lines, batteries and renewables to support the energy transition.

Read More: Iron ore’s ‘irrational’ rally past $100 triggers warning from Chinese media

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments