China’s building-season flop dents hope of iron ore market boost

The start of China’s peak construction season was supposed to finally boost demand for iron ore, which has endured a tempestuous year with prices now trading near 2022 lows. But the bounce hasn’t happened, with traders now puzzling over what could be the next catalyst for a price rally in the crucial steelmaking material.

China’s usual boom period for infrastructure construction and steel-related demand in September and October has so far offered no reprieve for investors in the iron ore market, which just notched its longest streak of weekly losses on record. The economy continues to contend with severe housing slump and virus-related lockdowns.

Bets that fresh financing for the property sector — which accounts for a third of steel consumption — will aid demand recovery during the peak season have since unraveled, with the 100 biggest real estate developers seeing new-home sales in September plunge by a quarter. That’s even as financial regulators rush to stem the liquidity crisis, telling the nation’s six largest banks to offer up at least 600 billion yuan ($85 billion) of net financing.

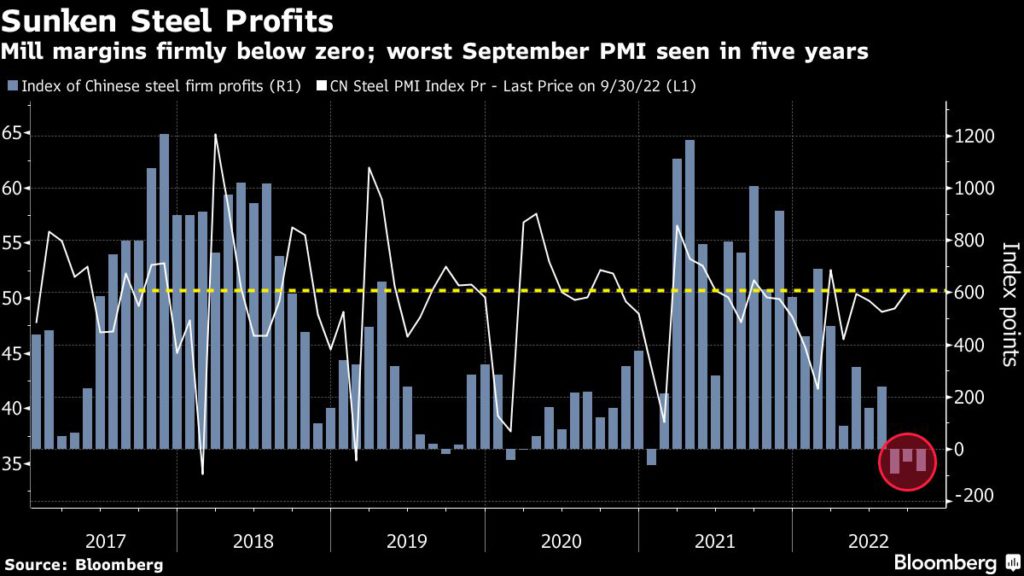

While steel mills typically restock iron ore supplies before the National Day holidays at the start of October, their profit margins are also languishing and they’re limiting purchases to a needs-only basis. Meanwhile, September saw China’s purchasing managers’ index rising only marginally to 46.6 — a reading below 50 suggests contraction in the steel industry.

“It’s certainly the worst autumn since 2015,” Tomas Gutierrez, analyst at Kallanish Commodities, said in emailed comments. “Real estate is far too big a part of the whole economy and no other sector can expand rapidly enough to make up for lost construction steel demand.”

Gutierrez was referring to the period seven years ago that also saw a sharp slowdown in China’s property and factory activity. Added to that, global iron ore supplies were expanding rapidly, and futures traded as low as $40 a ton.

The raw steel-making ingredient that’s crucial for construction, machinery and automotive sectors is regarded a barometer of Chinese growth. The World Bank’s most recent forecast shows the nation’s economic expansion will decelerate to 2.8% this year, a mere third of the 8.1% rate in 2021. That bleaker outlook will limit the upside in iron ore prices.

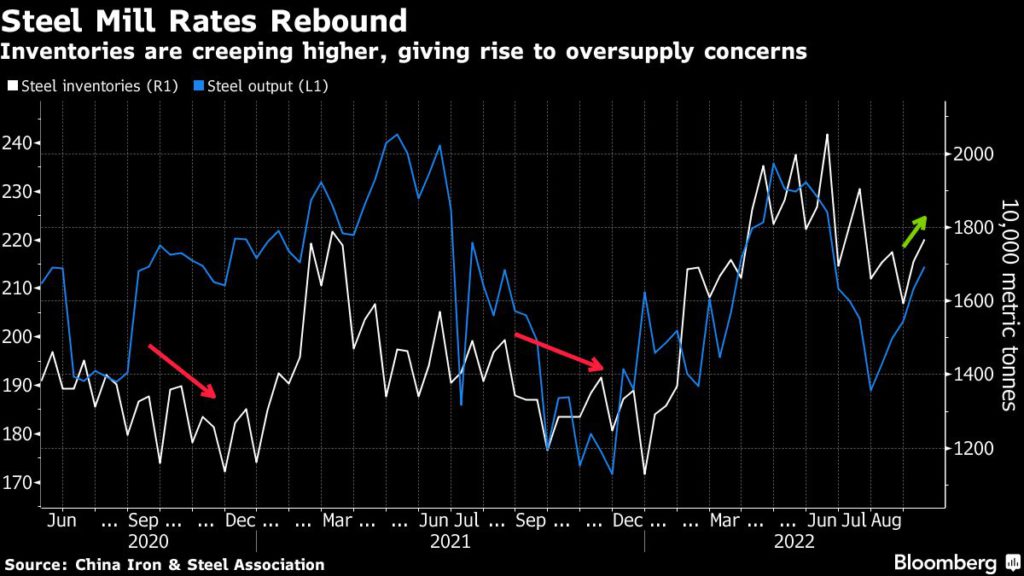

With the Chinese economic outlook and its consumer confidence appearing grim, steel prices will be capped, said Kamal Ailani, a senior analyst at McCloskey by OPIS, which is owned by Dow Jones & Co. Layered atop economic woes, the growth in China’s steel production in September has also triggered concerns about oversupply, he added.

To be sure, not all market players are pessimistic, with some analysts seeing prices at least stabilizing by the fourth quarter.

“In my years in steel, 2015 is probably the worst year, and, fortunately, we are not there yet,” Richard Lu, a senior analyst at CRU International Ltd., said in emailed comments. CRU is forecasting some improvement in the last quarter of the year, with steel demand supported by new infrastructure projects.

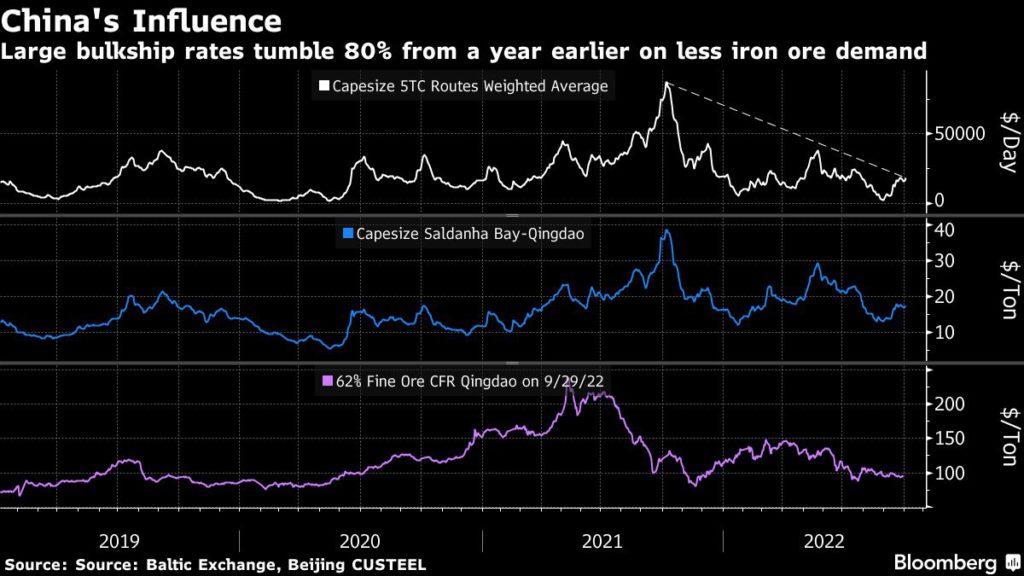

Meanwhile, Ailani sees iron ore prices trading down from current levels, but still “well supported around $85 a ton” in the fourth quarter. Below that level, mid to small-sized miners may have to reduce production given increased costs, he said.

Iron ore in Singapore was 2.8% lower on Tuesday at $94.25 a ton by 2:12 p.m., while prices in Dalian lost 2.1%. Steel rebar and hot-rolled coil futures fell in Shanghai.

The slump in China’s construction sector has also crushed global demand for bulk ships. Freight rates to hire a Capesize vessel have plummeted almost 80% from last October, most of it due to weaker iron ore demand from the nation, said traders and shipbrokers.

For now, shrinking stockpiles are still providing some buffer for the steel market, although investors will be eyeing the looming Communist Party congress — a twice-a-decade event during which President Xi Jinping is expected to win a third term —- that starts October 16 for signs that the government will make any changes to its tough tack on Covid-19 and property deleveraging.

(By Liz Ng and Ann Koh)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments