China’s 2020 refined nickel imports slump to 6-year low

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

China has bailed out the copper and aluminum markets by importing record amounts of the rest of the world’s surplus metal.

Not so the nickel market, however.

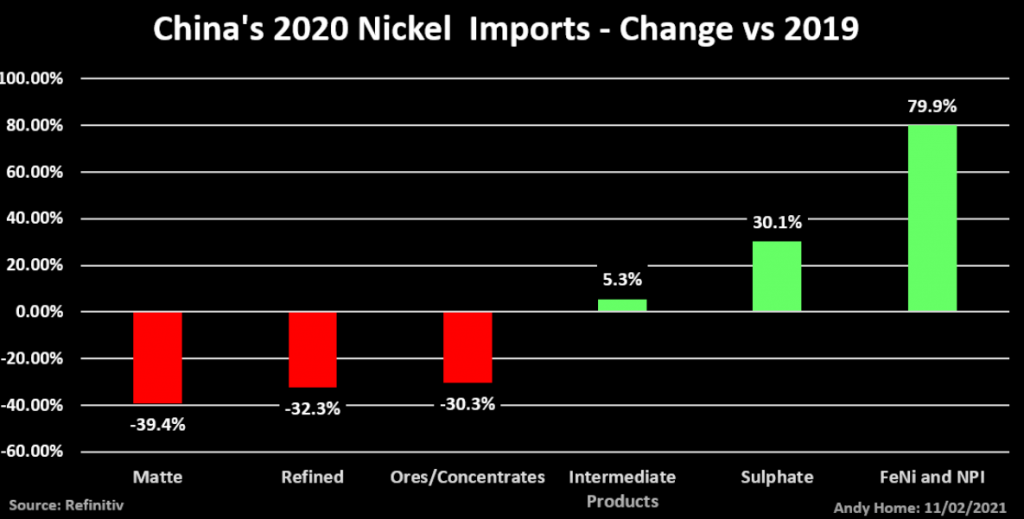

Chinese imports of refined nickel fell by 32% year-on-year to 130,700 tonnes in 2020. It was the lowest annual total since 2014.

This has not held back the London Metal Exchange (LME) nickel price, currently trading close to 17-month highs at $18,675 per tonne.

One way for China’s nickel sulphate producers to fill the emerging supply-demand gap would be to turn to refined metal as a feedstock

However, China’s lack of import appetite is evident in abundant LME stocks, which stand at 249,846 tonnes, up from 156,000 tonnes at the start of 2020. It is also clear to see in the LME contract’s loose date structure, the benchmark cash-to-three-month period closing out Wednesday at a $45 contango.

It’s not that China isn’t buying lots of nickel. It’s just that it’s buying lots of raw material, leaving the refined market undisturbed.

The driving force remains China’s stainless steel sector, which is absorbing ever more Indonesian nickel pig iron (NPI).

But there are signs that growing demand from the battery sector is starting to make an impact on China’s nickel trade landscape. A Chinese nickel sulphate supply squeeze may accelerate that shift.

It could, though, also trigger another reformulation of entire nickel supply chain.

Ferrous flows

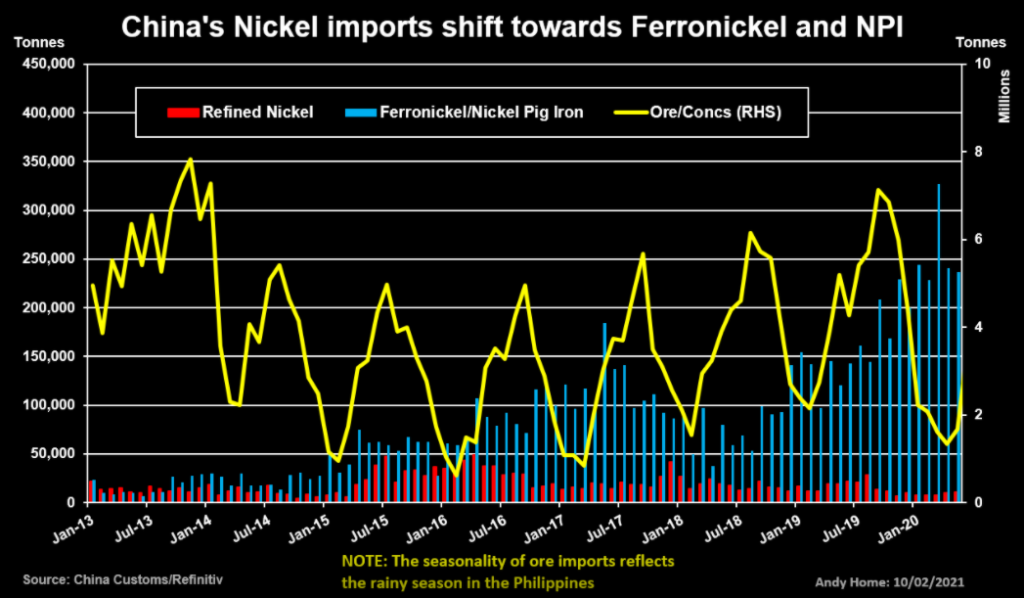

While China’s refined metal imports slid further last year, those of ferronickel and NPI boomed, up 80% on 2019 at 3.4 million tonnes.

The lion’s share is now coming from Indonesia, which has been building out NPI capacity after miners were banned from exporting nickel ore at the start of 2020.

The flow of Indonesian NPI to China’s stainless steel sector mushroomed from just 600,000 tonnes in 2018 to 2.7 million tonnes last year.

The flip side of the Indonesian export ban was a 30% reduction in Chinese imports of ores and concentrates last year. Alternative suppliers such as the Philippines and New Caledonia were unable to compensate for the loss of Indonesian material.

The shifts in raw material flows since the Indonesian export ban shouldn’t distract from the core fact that all these nickel products are headed for China’s stainless steel sector.

It is the sharp recovery across the country’s ferrous sector that has been lifting demand for nickel raw materials, whether ore, NPI or ferronickel.

China’s stainless mills have enjoyed their share of the demand boom created by rapid covid-19 recovery and government stimulus.

The country’s stainless production rose by 4% in the third quarter of last year, while that in the rest of the world fell by 9%, according to the International Stainless Steel Forum.

Electric charge

China’s import landscape reflects the fact that nickel usage is still dominated by stainless steel.

That is expected to change as demand from the battery sector grows to meet the shift to electric vehicles. Nickel’s material share of lithium-ion batteries has been rising as manufacturers seek ever more charging capacity at ever lower cost.

“Automotive electrification is expected to represent the single-largest growth sector for nickel demand over the next twenty years,” according to a report prepared for the European Commission by research house Roskill (“Study on future demand and supply security of nickel for electric vehicle batteries”, January, 2021)

Roskill forecasts global nickel demand from the battery sector to increase from 92,000 tonnes in 2020 to 2.6 million tonnes in 2040.

It’s precisely that sort of forecast that has given the nickel market an electric buzz among investors.

Particularly since battery manufacturers need a special kind of nickel – nickel sulphate – that can only be made from refined metal or intermediate products such as mixed-hydroxide-product or mixed-sulphide-precipitate.

Battery pull

This alternative demand stream is starting to show up in China’s nickel trade.

Imports of what China’s customs department terms “intermediate products smelted by nickel hydrometallurgy” rose by 5% to 354,000 tonnes in 2020. This flow of sulphate feed material was dominated by Papua New Guinea, the location of the Ramu mine, and New Caledonia.

Imports of nickel sulphate itself registered the second highest year-on-year growth by nickel product, up 30% at 5,600 tonnes.

Sulphate demand in China is running white hot right now as the battery supply chain struggles to catch up with rebounding electric vehicle sales.

Fastmarkets has lifted its assessment of the China ex-works sulphate price to a record high amid a shortage of material and rising input costs.

The out-performance of this battery sub-stream of the nickel market is already generating two different reactions, one bullish for price and one bearish.

Filling the gap

One way for China’s nickel sulphate producers to fill the emerging supply-demand gap would be to turn to refined metal as a feedstock.

There are signs this is already happening with Fastmarkets, lifting its assessment of Chinese briquette prices to reflect encroaching demand from the battery supply chain.

An extension of this trend would likely translate into a recovery in refined metal imports with a flow-through to currently high LME inventories.

However, the widening premium for nickel sulphate may also reshape the industry in a price-negative way.

Indonesian producers of NPI are now looking at the economics of converting their output into nickel matte, which could than be processed into sulphate.

It’s technically possible but comes with relatively high costs and a relatively heavy carbon footprint. But given the current high nickel price and the simultaneous premium for sulphate, Chinese operators such as Huayou Cobalt look as if they are going to give it a go.

This new processing pathway from NPI to sulphate compliments an existing Indonesian effort to produce battery-grade nickel directly from laterite ore.

If either proves commercially successful, it would upend the argument that only refined nickel or specific intermediate products can generate the right sort of nickel for battery production.

That would herald another shift in nickel’s infinitely malleable mix of price drivers.

It’s worth remembering the nickel industry has impressive form when it comes to technical innovation.

Nickel pig iron now dominates China’s imports but as a commercial product it didn’t exist until 15 years ago. It was born out of the high prices of the mid-2000s.

Bulls betting on yet higher nickel prices this time around should be careful what they wish for.

(Editing by Jane Merriman)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments