China shifts approach to fatal coal mining accidents to ensure supply security

The latest fatal accident linked to coal production in China, this time caused by a fire in a miner’s building in Shanxi province, has prompted another government campaign to protect lives in hazardous industries.

The Shanxi blaze, which killed 26 people and injured another 38, isn’t the worst coal accident in China this year. In February, a landslide at an open-pit mine in Inner Mongolia left 53 dead, the nation’s deadliest industrial disaster since 2019. Coal mine explosions also killed seven in Liaoning in June and 11 in Shaanxi in August.

In mid-September, China’s National Mine Safety Administration said it would amend laws and step up enforcement to eradicate illegal and excessive mining activities that it blamed for the fatal accidents. Six days later, a fire broke out in a Guizhou mine, killing 16.

But unlike previous years, the efforts to rectify unsafe work practices are hardly registering on the nation’s production of its mainstay fuel. The authorities are adopting a lighter touch to ensure energy security isn’t compromised, and that blackouts, which have crippled the economy in the past, are avoided.

In recent times, the prospect of a round of safety inspections in a mining hub like Shanxi, which produced 1.3 billion tons of coal last year, would have fueled concerns over disruptions to output and a rally in prices. This year, it’s been met with a shrug. Thermal coal prices have fallen 2.2% this week and are about a third lower than they were a year ago.

The bleak truth is that, even with broad improvements in worker safety, lots of people still die every year mining coal in China. Total deaths in 2022 were 245, according to the mine safety administration.

The firms at fault are usually smaller, private outfits, which cut corners to boost production to meet government targets or to profit from periods of higher prices. The bigger state-owned firms have much better records. The largest, China Shenhua Energy Co., had a total recordable incident rate of nearly zero in 2021 and 2022, better than its global rivals, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Four of its workers died in accidents last year, versus a peer average of three.

In past years, officials have fanned out across the country after particularly bad accidents, halting production at nearby mines to make sure proper safety standards were in place. The disruptions would limit supply and lead prices to spike.

Periodic shortages

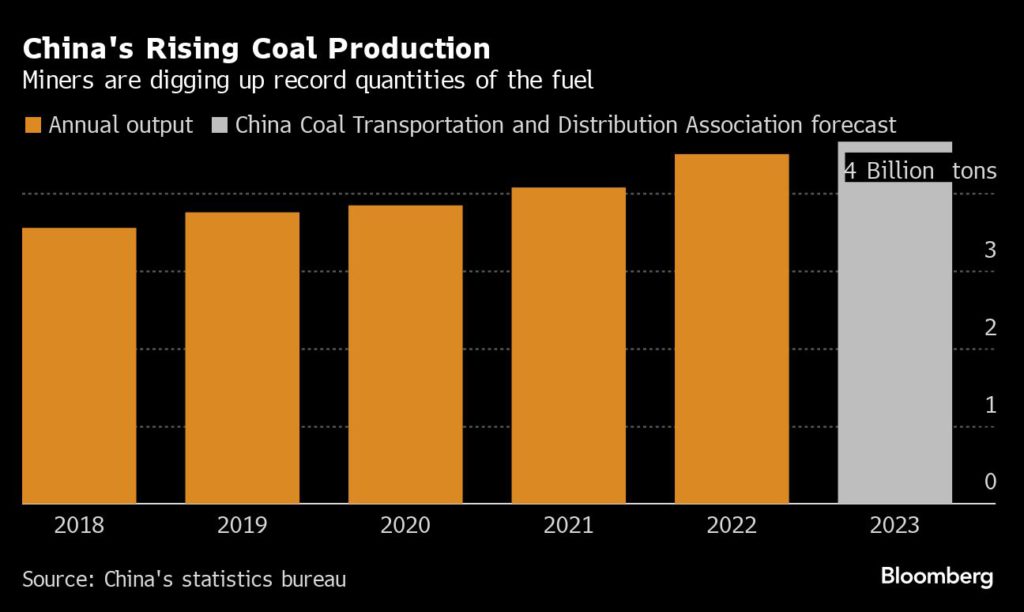

But the periodic lack of coal has also contributed to nationwide power shortages. The government’s broad response has been to keep lifting production to all-time highs. That drive for energy security has also shifted the way China deals with mine accidents, according to Shenhua.

In September, executives told investors that the government has adopted a new system this year where it rated mines on safety standards, and would allow operations with high grades to keep operating after accidents that might have led to suspensions in the past, according to a note from Morgan Stanley at the time.

Neither Shenhua nor the mine safety administration responded to requests for comment.

That’s not to say there’s been zero impact. The China Coal Transport and Distribution Association’s latest forecast is for national output this year to rise modestly to a record 4.66 billion tons, according to a briefing on Wednesday. But that represents slower growth than previous estimates. Having all but assured its annual target, the government is discouraging miners from pushing too hard at the end of the year amid the heightened scrutiny on safety, it said.

Read More: China coal hub approves mega-mine that can produce for 97 years

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments