China is already winning the next great race in electric cars

Battery packs clamber up a conveyor belt before dropping into a flame-proof chamber, where they are crushed into gray metallic mush, a cocktail containing the car fuel of the future.

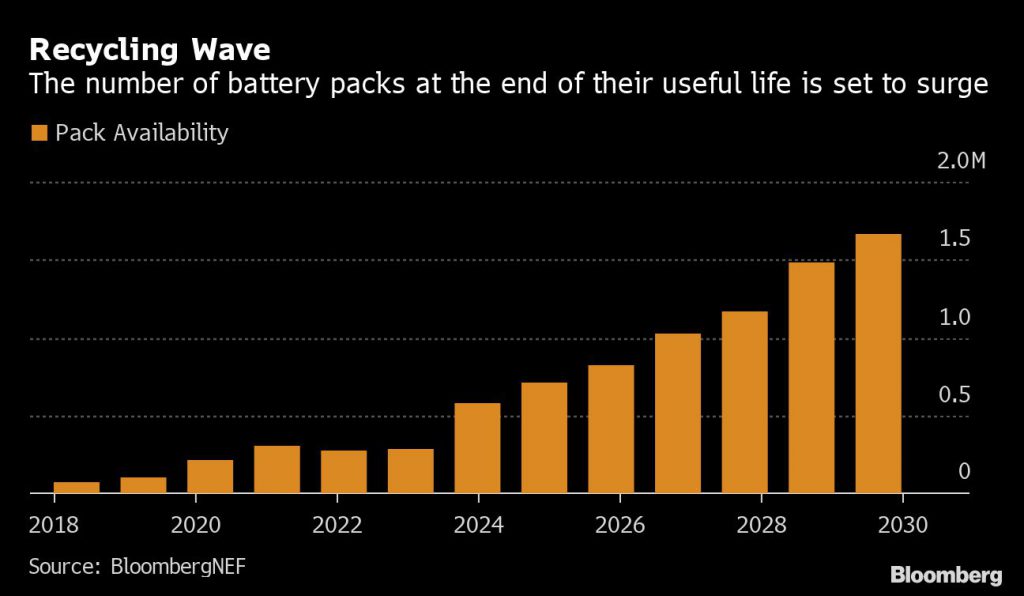

The facility separates components like cobalt, nickel, graphite and lithium from waste plastic particles. Factory owner Duesenfeld GmbH is bracing for a tidal wave of spent batteries as carmakers move beyond combustion engines in huge numbers. Over the next decade, the pile of retired power plants will grow from almost nothing to 1.6 million tons annually, according to BloombergNEF.

Deployment of about 140 million electric vehicles by 2030 will require 3 million tons more copper a year, 1.3 millions tons more nickel and about 263,000 tons more cobalt

The recycling push betrays a dilemma at the center of the car industry’s green reincarnation: Battery-powered cars might not have the carbon footprint of their combustion siblings, but they are still toxic at heart. The power cells contain raw materials mined in politically and environmentally delicate places, like Bolivia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and if estimated growth rates are any guide, demand will eventually outstrip supply.

“At some point it won’t make sense anymore to dig for raw materials, because enough batteries are available,” said Duesenfeld Managing Director Christian Hanisch in his office in Wendeburg, located in the heartland of northern German car production, where Volkswagen AG has its headquarters and some of its biggest facilities. “As a carmaker, I’d seriously consider safeguarding the raw materials. A deposit system might work.”

There’s another hard economic truth facing recycling companies and vehicle manufacturers alike. The process comes at a cost that’s unlikely to be covered by the value of the extracted materials, which are less precious than the substances retrieved from catalytic converters, for example. That’s set to expose electric cars to an additional cost burden, further widening the profitability gap to conventional vehicles.

The transition to battery power will dramatically increase the thirst for raw materials. Deployment of about 140 million electric vehicles by 2030 will require 3 million tons more copper a year, 1.3 millions tons more nickel and about 263,000 tons more cobalt, according to Glencore Plc, a top producer of all three metals. In the case of cobalt, that surge will dramatically outstrip total current mined production, which stood at 150,000 tons in 2018, according to BloombergNEF.

It’s such calculations that will make recycling inevitable. Already, battle lines are forming, and China is emerging as a leader in the field. Unlike in the U.S. and Europe — where high transport and energy costs are a burden — recycling vehicle batteries is profitable in China, based on the value of the raw materials alone. That’s nurturing an industry ready for expansion and in a pole position to compete with western efforts.

“In both the U.S. and Europe, we tend to look at recycling as a question of how we should take care of batteries that reach the end of their life,” said Hans Eric Melin, founder of Circular Energy Storage, a London-based consultant. “In China and South Korea they look at it from the other direction; they tend to ask themselves how to supply production of battery materials, and recycling is one way to do that.”

One Chinese player is Ganzhou Highpower Technology Co., which plans to raise recycling of used-car batteries sixfold next year, part of an ambitious plan by the government to boost recycling power to 1 million tons annually by 2030 from about 60,000 tons now, according to BloombergNEF.

“Recycling has been a very popular topic, and there’s been a lot of companies joining the market,” said Ou Hancheng, general manager of Ganzhou Highpower. “The electric vehicle producers are already realizing the importance of recycling.”

One complicating factor for recycling companies is that prices for cobalt, lithium and nickel have gyrated wildly in recent years, making calculations harder. Cobalt sulfate quadrupled in the two years to March 2018 on concern over potential shortages, and have since plunged by about two-thirds after supplies flooded the market. Lithium prices have also tumbled after a dramatic surge that saw the battery metal triple in the three years through May 2018.

But a bigger issue is that extracting these materials from spent batteries will come at a cost that carmakers and consumers may not have fully realized, said Marc Grynberg, the chief executive officer of Belgian chemicals company Umicore SA.

“What still needs to percolate through to the industry and consumers is that the end of life, whatever it is, will come at a cost, and that has to be incorporated into the selling price,” Grynberg said. “There’s a fee to be paid.”

Umicore already recycles batteries for Tesla Inc. at a plant south of Antwerp. Its approach differs from Duesenfeld’s mechanical removal in that the batteries arrive discharged and stripped of casings and wiring, before being smelted into liquids to be analyzed and extracted in a process known as wet chemistry. Grynberg predicted major investments in recycling, saying that beyond his own company, there’s only been “modest” attention paid so far outside of China to salvaging spent batteries.

German chemicals company BASF SE, which claims more than a century of expertise recycling materials, also wants to play a bigger role, though the company cautioned that integrating the entire process—from collecting the used batteries to dismantling the cases to onward shipping of the extracted materials—will require a robust local value chain.

“Given the capital-intensive nature of battery recycling, partnering along the value chain is a critical aspect for success,” said Peter Schuhmacher, head of BASF’s catalysts division. “The economies of scale very much depend on the number of batteries coming back into the recycling market.”

For a mass producer like Volkswagen, the pressure is palpable. The world’s biggest carmaker is rolling out the industry’s most aggressive electric-model lineup, expecting sales of 22 million battery-powered vehicles over the next 10 years.

“It’s our goal to get to a point where recycling is economical, provided there’s the scale and availability of materials,” the company said. “Electric mobility has significant challenges that can only be resolved with the right partners in the longer term.”

(By Elisabeth Behrmann, Andrew Noel and David Stringer, with assistance from Masumi Suga and Martin Ritchie)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Balter

I’m not reading any further… batteries are not “fuel” there is your first serious flaw in understanding why liquid hydrocarbons are still the best option.