Carbon offset trading is taking off before any rules are set

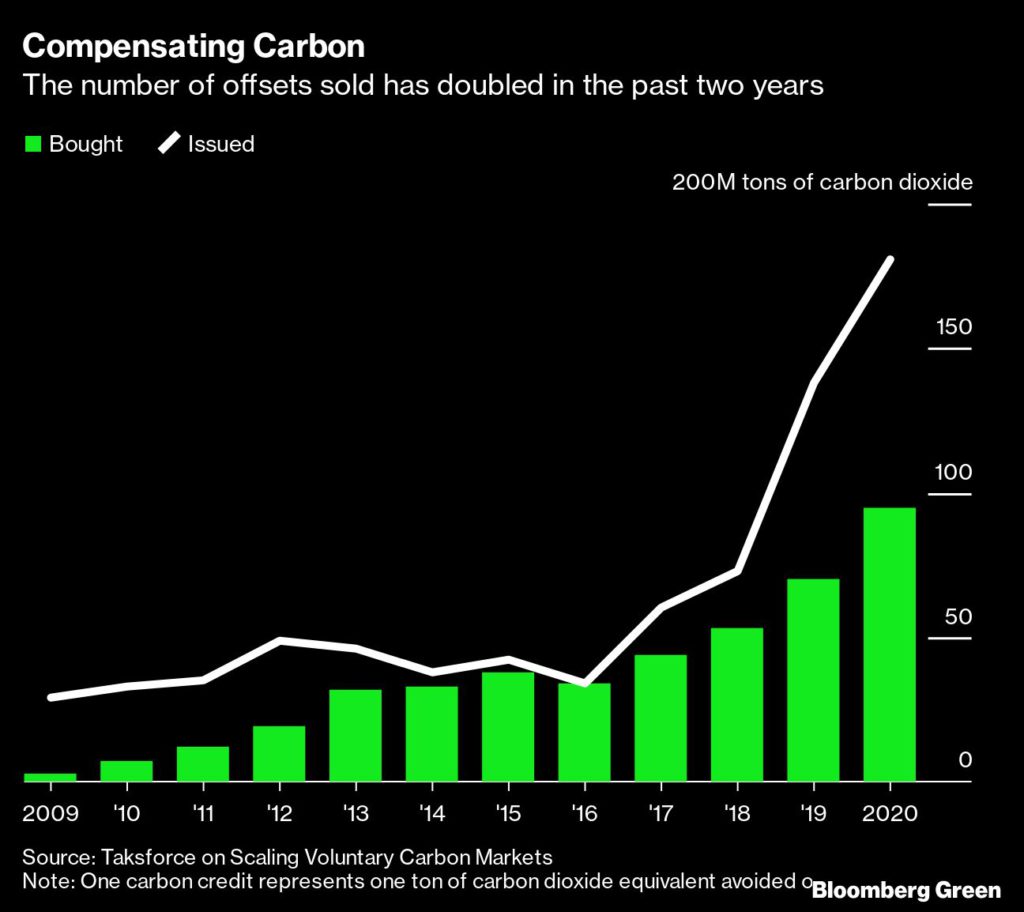

The most ambitious attempt to set a high standard for carbon offsets is getting left behind as exchanges start trading contracts before the rules are finalized.

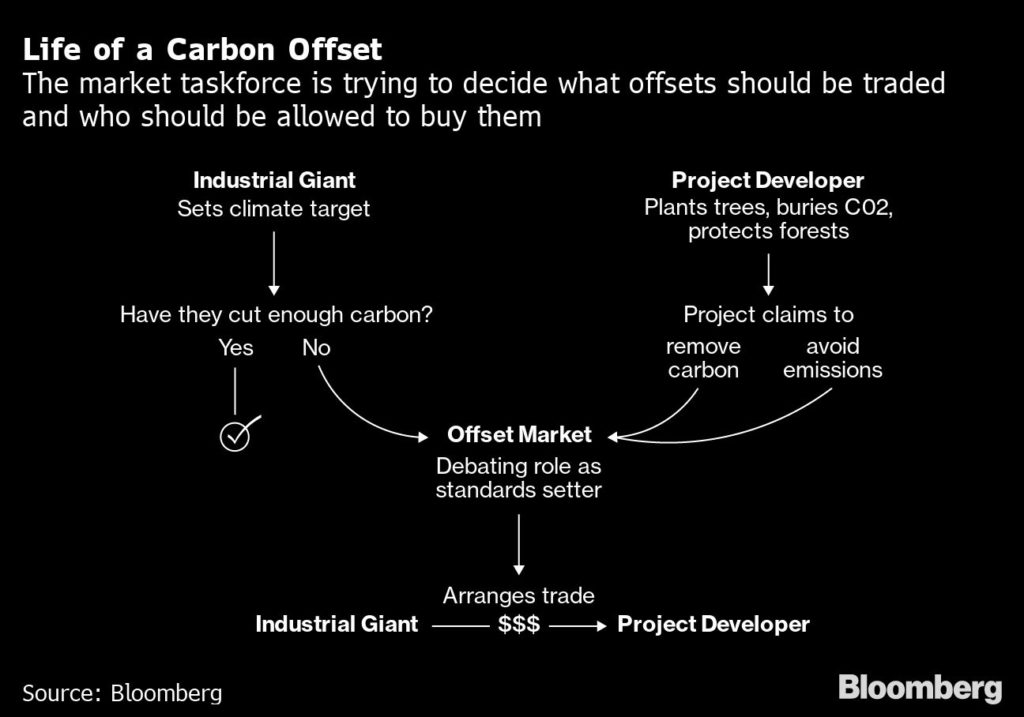

The Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, launched by former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney and Standard Chartered Chief Executive Officer Bill Winters, is populated by hundreds of bankers, airline executives, sustainability experts, commodities traders, scientists and other business leaders. On Thursday, after almost a year of internal wrangling, the group set out its final recommendations for how to define an offset, a sort of token that companies may use to cancel out their pollution.

The next step is to establish a governance body that will determine a set of rules — based on the taskforce’s recommendations — to drive up demand for credits that deliver on their climate promises. But commodity exchanges in Chicago and Singapore are rushing to start trading contracts this year, before the standards are decided, raising concerns the taskforce will fail to provide any kind of structure to a market that already has no government oversight.

Getting the contours of the market right could create a powerful weapon in the fight against climate change by funnelling much-needed money to important environmental projects around the world. But encouraging the trading of contracts without clear rules about what a high-quality offset is and how the credits should be used to account for a company’s total emissions could have devastating consequences. Companies could use questionable offsets as a license to keep polluting, resulting in more CO₂ accumulating in the atmosphere.

A key objective of the taskforce is to come up with a “Core Carbon Principle” label that will be used to mark offsets that meet its standards, akin to how groceries might be labeled organic. Members have spent months arguing over the criteria for inclusion, with sharp divides over how high to set the bar, even as companies have been itching to start trading.

“We need to build this thing and launch it,” said Tim Adams, head of the Institute of International Finance, which is helping to organize the taskforce. Sonja Gibbs, another IIF official, said the taskforce has already done a large part of the legwork to define the principles, giving direction to anyone wanting to adopt them now.

The non-binding recommendations issued on Thursday suggest that:

- No offsets should be excluded from the market, though “high-quality” credits should get a special label

- Each credit should be tagged with “additional attributes” such as its location, or whether it removes CO₂

- There should be a robust legal framework behind all credits sold

The hope is that the to-be-formed governance body will nail down the criteria for a high quality “CCP” label so trading can start in 2022. But some exchanges aren’t waiting. CME Group Inc., one of the world’s largest derivative exchanges, has already started transactions. Singapore is planning to start trading CCP-aligned contracts before world leaders gather in Scotland for climate talks in November, said Adams.

The trading will be facilitated by Climate Impact X, a new platform backed by Singapore’s state investment firm, stock exchange and largest bank. The Singapore trades will likely be based on rough guidelines that have been set out by the taskforce so far. It’s not clear whether those contracts could be later amended to fit with the CCPs once they are final. Climate Impact X declined to comment.

“They’re basically saying they promise to procure and deliver CCP-certified credits to their counterparties in the future,’’ said Derik Broekhoff, a taskforce member and senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute. Buyers will probably pay more than they would purchasing credits directly from brokers or project developers, in exchange for the guarantee that they’re buying high-quality offsets endorsed by the taskforce. “The sellers will then be on the hook to obtain and deliver the credits,” he said.

High-quality offsets that actually remove additional carbon from the atmosphere are extremely rare. Credits based on avoiding emissions made up 96% of all contracts issued last year, according to data compiled by the taskforce, mostly by seeking to prevent trees from being cut down or supporting renewable energy projects. Climate scientists are cautious of using such credits to erase a company’s ongoing pollution because it’s very difficult to determine how much carbon, if any, has really been saved.

CME launched trading for carbon offset futures earlier this year, accepting Corsia-eligible offsets issued by Verified Carbon Standard, American Carbon Registry, and Climate Action Reserve. The first trade took place in March and included independent oil traders Vitol and Mercuria. The bourse also plans to start nature-based offset contracts on Aug. 1.

While CME is a member of the taskforce, it stopped short of saying it would adopt the CCP principles when they are issued. “We are not climate change experts,” it said in a statement. “We are driven by customer demand and we will continue to be guided by our customers’ preferences and feedback.”

The decision by exchanges to move ahead with trading before the CCP label is finalized has reignited concerns from some taskforce members that the organizers of the group are willing to sacrifice quality for quantity. Carney has said the market could be valued at $100 billion by 2030, up from about $300 million in 2018, with demand growing rapidly as scores of companies and countries set net-zero targets.

“The taskforce isn’t really moving the needle on quality,’’ said Owen Hewlett, a member of the taskforce and chief technology officer at offsets registry Gold Standard. The focus is on building a large, efficient market to meet demand, he said, rather than working out the thorny issues of how companies should use offsets. “This is why there’s so much suspicion.”

The taskforce is also constrained by its lack of authority. Offsets trading is voluntary, and project developers are reliant on companies being willing to fund their programs. For some, it’s a question of getting trading to take off as quickly as possible, so more funds can flow to boost environmental protection, while slowly moving toward better standards — and eventually even government regulation.

“Let’s recognize and applaud those who are doing something, of course, and encourage them to do more,’’ said Isabel Hagbrink, director of communications at project developer South Pole, which sits on the taskforce. “But understanding that ultimately, governments have to step in and step up and say, ‘Look, this is not enough. This can’t be all voluntary climate action.’”

(By Jess Shankleman, with assistance from Akshat Rathi, Ishika Mookerjee and Will Mathis)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

BOB HALL

If there is a way to make money while adding no value this is it. What is next? ‘an exchange for hangman’s rope’