Bolivia pitches Wall Street on bonds linked to lithium

Bolivia is weighing the sale of as much as $1 billion in so-called green bonds in New York this year, according to the country’s finance chief.

The Andean nation is in discussions with Wall Street to sell debt earmarked for mining lithium — a key component in electric—vehicle batteries, Economy Minister Marcelo Montenegro said.

By tapping the market’s demand for clean-energy investments, the nation expects to drive borrowing costs to 10% or lower, Montenegro said, even as its existing debt trades at levels suggesting traders are bracing for a default.

“This is tied to something very important for Europe and elsewhere, which is the rapid move toward clean energy use,” Montenegro said in an interview in La Paz Friday. “If I just blundered into the market thoughtlessly, and did a normal sale with the banks that help us I’d have to pay 18% or 19%, if I even managed to sell any bonds at all.”

Bolivian officials have met with institutions in New York over the possible emission of between $500 million and $1 billion, he said. He declined to name them.

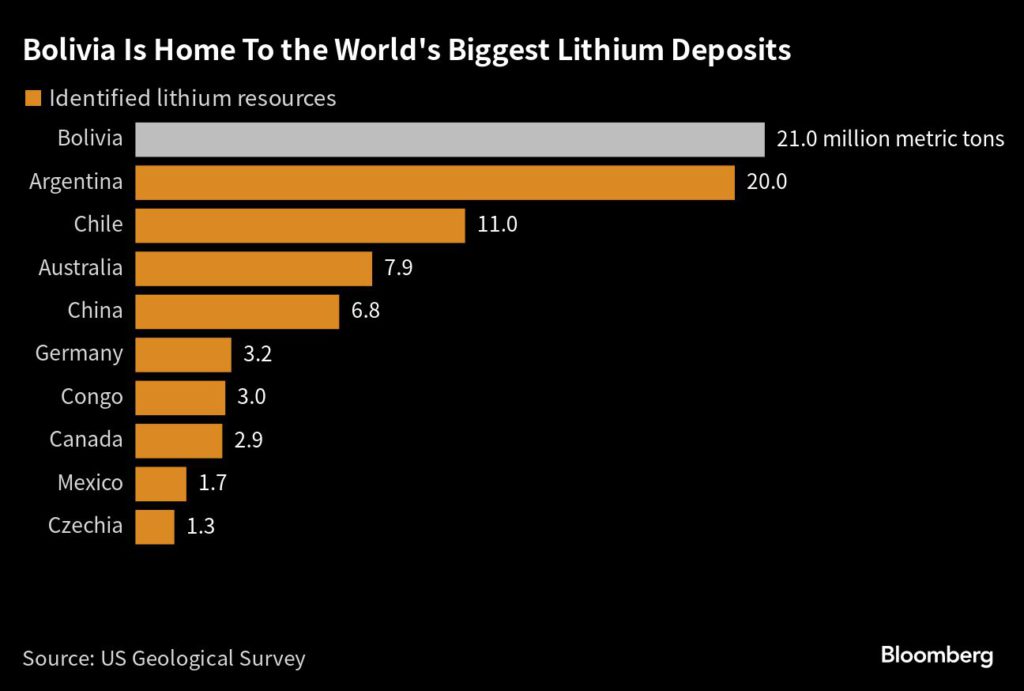

A giant salt flat in the Bolivian Andes contains the world’s largest lithium deposits. But while Bolivians have long anticipated a bonanza from the metal, they have yet to extract it in commercial quantities. Bolivian brine has high levels of magnesium, which make its lithium less pure and costlier to produce, while the nearest port is at least 500 kilometers away in Chile.

A history of political and social unrest and a state-led approach to natural resources have also deterred private investors, as has the recent plunge in prices.

Bolivia’s sovereign bonds have returned 19% this year, among the best performances in a Bloomberg index of emerging market dollar debt. Montenegro attributed the rally to a 10-point plan the government announced last month to address a dollar shortage and ease restrictions on exporters.

Even so, the notes trade at distressed levels and the extra yield investors demand to hold the bonds hovers around 1,786 basis points over US Treasuries, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. data.

‘Manageable’ payments

Montenegro said that the nation’s outstanding bond schedule is “manageable,” adding that the government has demonstrated its willingness to honor obligations. Principal payments start in 2026 on a $1 billion note that matures in 2028, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

A sovereign bond sale was already approved by congress last year. But in future, the government is likely to find it harder to borrow abroad after lawmakers in the ruling socialist party split between those loyal to President Luis Arce and allies of former President Evo Morales, effectively depriving the government of its majority.

“For multilateral lenders, Bolivia has a lot of space for important projects, but it’s in congress that they have put a lot of restrictions on the topic,” Montenegro said.

Bolivia narrowly prevented a financial crisis last year by passing a law to allow the central bank to sell about half of its gold reserves. The most recent foreign reserve figures published in December showed the bank has sold almost all the gold it was allowed to, and has also used up nearly all of its cash.

Although the 16-year-old currency peg of about 6.9 bolivianos per dollar still exists on paper, in practice neither importers nor ordinary citizens can easily access currency at that price. A few blocks from the finance ministry, black market currency traders last week were offering dollars for more than 8 bolivianos each.

Bolivia’s annual inflation was 2.5% in February, among the lowest levels in the Americas. But some economists are predicting a spike in consumer prices this year as the dollar shortage makes imported goods more costly.

Montenegro said that the government’s subsidies of fuel, electricity and food will help keep a lid on inflation. He forecasts consumer price rises of 3.6% this year, and 3.5% to 3.6% in 2025.

(By Matthew Bristow and Sergio Mendoza)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments