Billionaire mining tycoon in India fights to clear Vedanta’s debt

For decades, Anil Agarwal cultivated a reputation as one of India’s great survivors. Starting as a scrap metal dealer, the billionaire magnate built a mining conglomerate to rival any other, weathering cash crunches, government friction and disputes with Indigenous people over expansion plans.

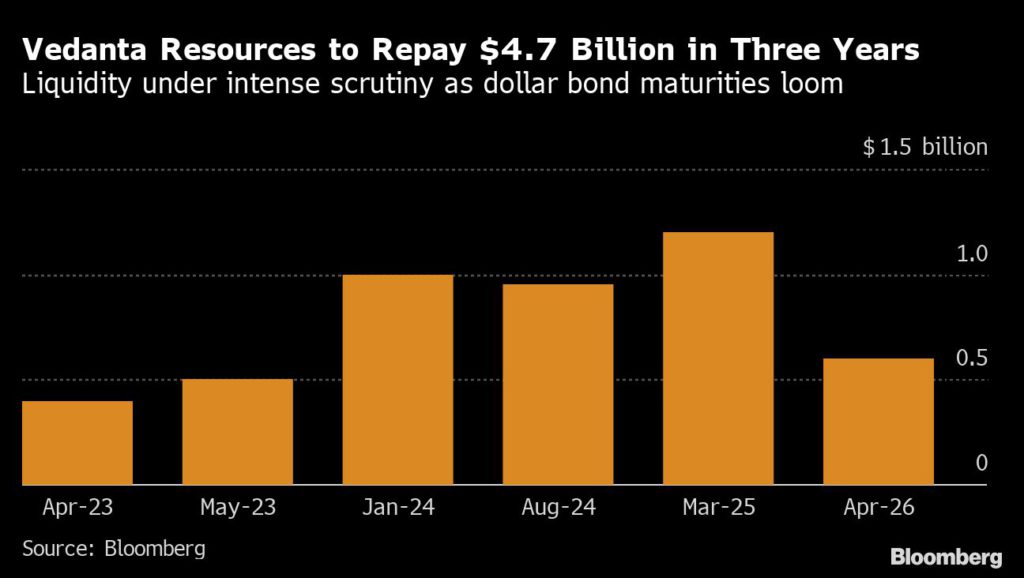

But in recent months, Agarwal has faced one of his toughest acts yet. The tycoon’s Vedanta Resources Ltd. has close to $2 billion of bonds to settle in 2024 — half of which is due in January. Short of that, his London-headquartered company risks getting cut deeper into junk and losing crucial access to funding. That’s bad news for one of India’s richest men, who has long dreamed of competing against Glencore Plc and BHP Billiton as the world’s dominant natural resources supplier.

Vedanta’s quest to raise cash comes during a rocky time for India’s business elite. Highly leveraged conglomerates are under increased scrutiny after a short seller accused Gautam Adani, once Asia’s richest person, of fraud across his infrastructure empire.

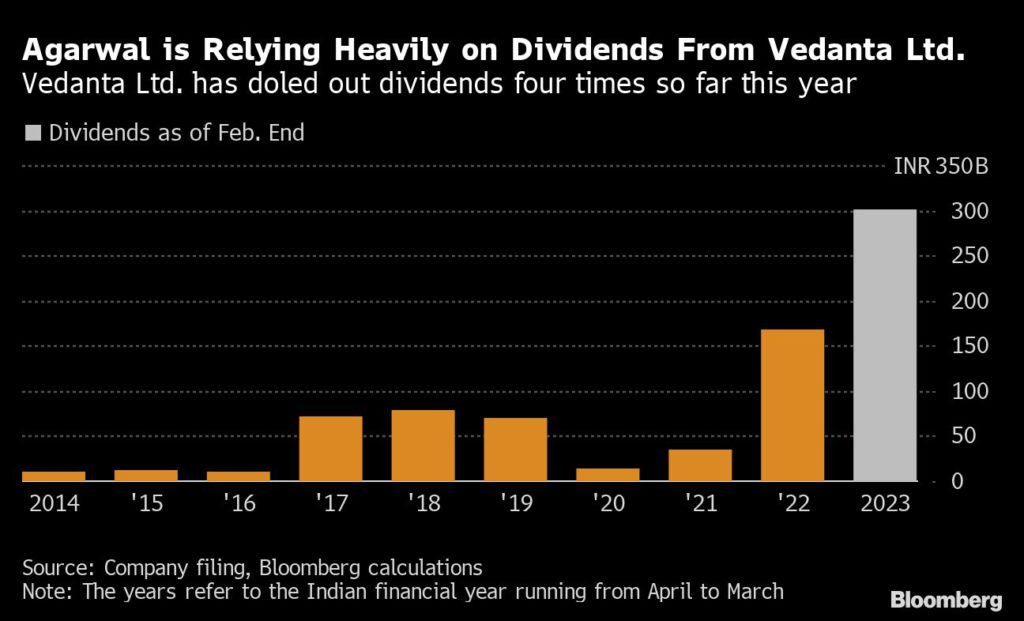

Though Vedanta’s debt pile is much smaller, the company’s bonds are rated near the lowest rung of gradings, raising the stakes for one of India’s largest miners to find a way out of the abyss. Investors are concerned about Vedanta’s ability to tap funds from its subsidiaries. Multiple dividends over the past year have depleted cash reserves, a troubling development amid high global interest rates and volatile commodity prices.

Added to the mix of unknowns is the man himself. Whether Agarwal’s brash style of deal-making is a risk or an advantage depends on whom you ask. He is often described as India’s version of a Russian-like oligarch: a scrappy entrepreneur who amassed his fortune by snatching up and reviving state-owned assets. A lavish life abroad followed, including buying a home in London’s posh Mayfair neighborhood.

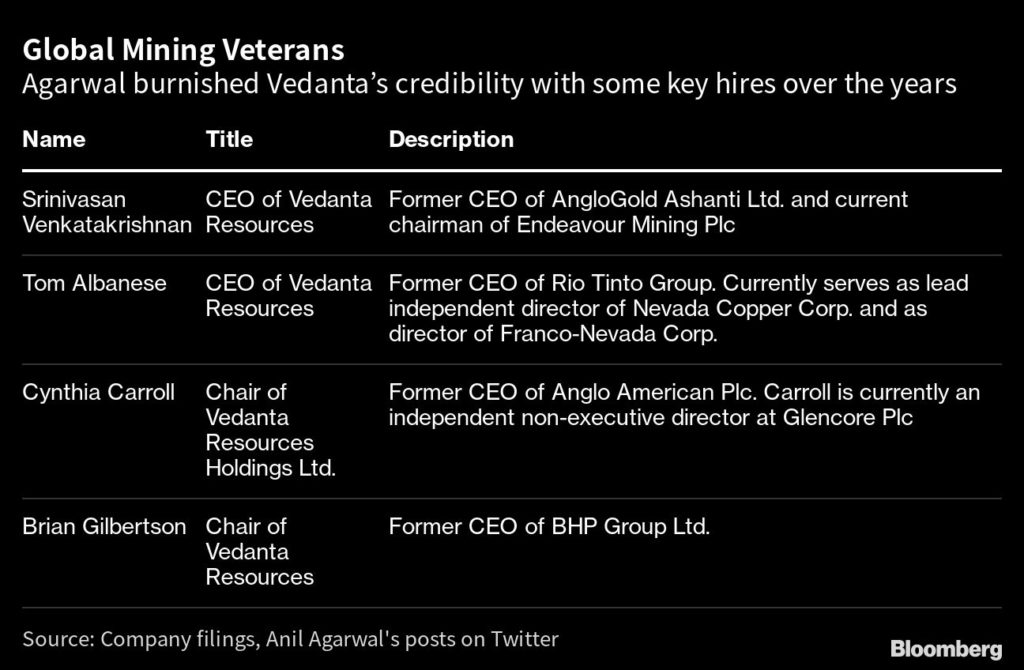

“Anil has always been a survivor,” said Tom Albanese, who served as chief executive of Vedanta Resources from 2014 to 2017. “He rose literally from the street; English isn’t his first language. He always felt he had something to prove.”

Vedanta Resources and Vedanta Ltd. didn’t reply to messages seeking comment.

The strength of Agarwal’s political connections could decide his fate. A core strategy to stay afloat involves offloading about $3 billion of assets to Hindustan Zinc Ltd., a subsidiary of Vedanta that’s partially owned by the Indian government. Officials have threatened legal action if the transaction goes through. New Delhi is worried that Agarwal’s zinc deal may impact valuations for the government’s own plan to sell its stake to bolster public finances.

“One easy way to raise cash has failed,” said Sunny Jiang, a fund manager at Haitong International Asset Management Ltd. “It looks like this time the company misjudged the government’s attitude.”

How Agarwal manages this moment could ripple through his portfolio. As Prime Minister Narendra Modi attempts to lure business from places like China, the industrialist has raised his hand to expand India’s manufacturing capacity. His holding company Volcan Investments Ltd. recently tied up with Taiwan’s Hon Hai Precision Industry Co. to build a $19 billion semiconductor factory.

At a media event this month in New Delhi, Agarwal insisted that Vedanta is well-placed to settle its debt. He said efforts to tear him down are rooted in jealousy at India’s rise as a global power.

“I have not defaulted anybody’s money,” he said onstage. “As long as there is no issue in governance, one can continue to grow.”

Building a giant

Agarwal hails from humble roots. Raised in the Indian state of Bihar, he took over his father’s business making aluminum conductors in the 1970s, and then ventured into trading scrap metal.

Vedanta was forged through a series of aggressive acquisitions. In 2001, Agarwal sought a majority stake in the government-owned Bharat Aluminum Co. His bid of 5.5 billion rupees was so large at the time that many questioned the company’s ability to fund the purchase.

But Agarwal’s public relations prowess helped him steer the narrative. He flaunted the acquisition of India’s biggest company during a media blitz and sought funds from banks by issuing a tender.

“All banks wanted to give us money,” he recalled in an interview with local media in 2016.

Within a few years, Agarwal expanded his empire substantially. He acquired Hindustan Zinc in 2002, and then placed successful bids for iron ore producers Sesa Goa Ltd. and Cairn India, despite having no oil and gas experience.

In 2003, Vedanta became the first Indian business to list in London before Agarwal took it private 15 years later. The company is now one of the largest natural resources suppliers in the world, with mining operations in India and Africa, and core strengths in zinc, lead and aluminum.

Agarwal’s supporters said the billionaire has excelled by developing rapport with banks and diversifying his businesses. He is sometimes described as a “compulsive entrepreneur” who runs his firms with a hands-on approach and has little tolerance for inefficiency or laziness.

“The longer I worked with him, the more I realized how smart he was,” said Albanese, the former chief executive of Vedanta Resources. “He doesn’t always give the impression of being the smartest guy in the room — but he is.”

A divisive character

Still, Agarwal has courted controversy, attracting the ire of environmental and human rights groups.

In 2018, Vedanta was forced to shut a lucrative copper smelter in southern India after skirmishes with the police left more than a dozen people dead. Villagers said the operations caused extreme pollution, a claim Vedanta has denied.

For several years, tribal communities clashed with Vedanta over bauxite mining in the state of Odisha. Protests at the time drew global attention and spread to New Delhi and London.

Key acquisitions have also soured. In Africa, the Zambian government has tried to liquidate Konkola Copper Mines Plc, a subsidiary of Vedanta. Officials accused the company of paying too little tax and lying about expansion plans. Vedanta has denied wrongdoing.

Hindustan Zinc is a key piece of Agarwal’s portfolio. In 2017, after rival miner Anglo American Plc rebuffed a proposed merger, Agarwal acquired the largest stake in the company, including through taking loans from a unit of Vedanta. Two years later, Agarwal sold the stake, keeping the global mining industry guessing about his motives — and whether the acquisition was more about him than anything else.

Whether Agarwal can steer Vedanta through the latest tumult remains in question. S&P Global Ratings raised an alarm in February over Vedanta’s ability to repay future maturities and Moody’s Investors Service cut the company’s debt deeper into junk this month.

Accessing capital markets is tricky because of high global interest rates and a decline in Vedanta’s bond value. Three out of six dollar notes of the firm are trading below 70 cents, a level that’s generally considered distressed.

Even with those challenges, Vedanta said in a Feb. 28 filing that it was “fully confident” of meeting upcoming maturities for the quarter ending in June. The company has tried to calm investors after a slump in the share price of its Indian entity — which coincided with the government’s warning over the Hindustan Zinc deal.

Among the options being considered to raise cash is divesting a less than 5% stake in Vedanta Ltd., according to people familiar with the developments, who asked not to be identified because the information is private. A stake sale will only be considered if other fundraising options fail, the people said.

Agarwal is increasingly relying on dividends from Vedanta Ltd. and Hindustan Zinc to pare his holding company’s debt, which totals around $7.7 billion. The Indian unit has paid four dividends in the current financial year ending in March, with total disbursements of about 301 billion rupees ($3.6 billion). An unprecedented fifth dividend is planned for Tuesday.

Lakshmanan R, a senior credit analyst at CreditSights, expressed confidence that Agarwal will live to see another day.

Agarwal has teetered on the brink of defaulting before, he said, “but he has always come out unscathed.”

(By Swansy Afonso, Divya Patil and Clara Ferreira Marques, with assistance from Ruchi Bhatia)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

BOB HALL

The deadly duo. Interest rates rise. at the same time bond value drops. Tell me if you have seen this before. BUT I agree that if it can be saved this is the guy to do it!