Biden’s climate bill is a put option on automakers’ big EV bets

Investors often use a term to describe the role the Federal Reserve plays as a backstop when markets crash: The “Fed put” refers to the central bank being willing to intervene and offer a form of insurance that downside risk is covered.

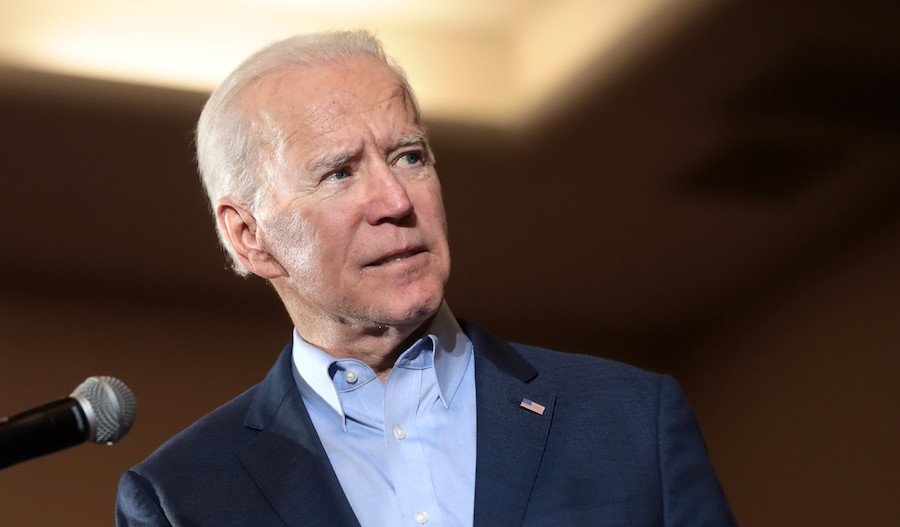

Considering what General Motors is saying about its electric vehicles, the company seems to view the Inflation Reduction Act that President Joe Biden signed into law in August as a sort of put that protects the big investments it’s making in battery and EV production. Well before the IRA passed, GM vowed to have the capacity in place to build 1 million EVs in North America by mid-decade.

“This was all in place before the incentive package came as a part of IRA,” GM CEO Mary Barra told Bloomberg Television on Thursday. To loosely borrow a famous cinematic phrase, GM was going to build the EVs; Uncle Sam will make sure consumers come to buy them.

“To really get all companies and consumers to move forward to EVs, this is very important,” Barra said. “We think that it will be helpful and allow us to continue to invest in the US.”

Barra’s comments follow an investor day GM held last month in which management said US tax credits of $3,750 or $7,500 per EV — depending on factors including where battery materials are sourced — will help bring profit margins on EVs in line with those of its gasoline-powered vehicles. Ford CEO Jim Farley has similarly praised the IRA, saying during his last earnings call that the company expects $7 billion worth of tax credits toward battery production by 2026.

Barra and Farley are among auto executives saying their customers are increasingly ready to go electric. If that’s the case, the IRA starts to look a bit like pork for the EV business. But that only would be true if massive growth in sales were a certainty.

EVs are still expensive and taking more market share almost entirely in premium and luxury segments of the US market. There are also risks to worry about including economic recession and rising interest rates. Some forecasters are convinced automakers’ plans for hundreds of new EV nameplates and ambitious production targets will lead to far more output than demand.

AutoForecast Solutions reckons that in 2025, automakers globally will produce 18 million to 19 million EVs, but sees just 15 million sales. Its prediction gets bleaker for 2029, when the firm sees global production of 38 million EVs that could go begging for sales of just 26 million units.

If the industry ends up running plants at just 68% capacity, as AutoForecast Solutions predicts, there’s going to be a whole lot of money lost. Automakers generally like their plants running at well more than 80% of capacity to ensure profitability.

Of course, forecasts can be wrong. Battery improvements and the proliferation of charging infrastructure may entice more consumers to buy plug-in vehicles. But Toyota is taking a more conservative approach, with its $28 billion EV investment trailing both Ford and GM.

Jack Hollis, the automaker’s executive vice president of sales for North America, said in an interview that he sees EV demand coming along slowly among non-luxury buyers, so the company will be offering a slew of gasoline-electric hybrids for years to come.

If GM and Ford are right with their big EV bets, government money will get them to profitability quicker. If Hollis is right and EVs don’t take off as quickly as Barra and Farley expect, Biden’s climate bill will act as a sort of insurance policy for profits.

(By David Welch, with assistance from Carol Massar and Tim Stenovec)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

BOB HALL

Building $120k electric SUVs is not in the interests of the nation – just the rich. How about building some ‘commuter cars’? How about the government taking the give away dollars and buying some basic transport for their staff? Car companies get the benefits of scale and the government gets clean transport. Rich people do not need $10k for each fancy car they buy! IRA will fuel inflation – not fight it.