Biden won’t ban fracking, but his clean grid would choke gas

During a town hall meeting Thursday, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden again assured shale producers that he wouldn’t ban fracking if elected. Then, in virtually the same breath, he touted his $2 trillion clean-energy plan, which aims to edge natural gas out of the power mix within 15 years.

The former vice president’s efforts to walk a tightrope on gas reflect the fossil fuel’s precarious place in the economy. For now, it’s an essential part of American life. Biden has been careful not to make an enemy of the industry, especially in the key battleground state of Pennsylvania, home to the largest U.S. shale-gas field. His policies may even, in the short-term, support the gas market.

But in the long run, the fuel may prove economically and environmentally untenable within the power sector, a key market for producers. Biden’s climate plan would only accelerate that outcome, with massive investments in wind, solar and battery storage giving those energy sources a leg up. And his goal of a carbon-neutral grid would severely curb, if not destroy, gas’s share of the pie in favor of cheaper, cleaner renewables.

“Decarbonization isn’t a debate — it’s a fossil-fuel death sentence,” said Kevin Book, managing director of ClearView Energy Partners. “It means a resource is going off the grid. That is the inevitable implication.”

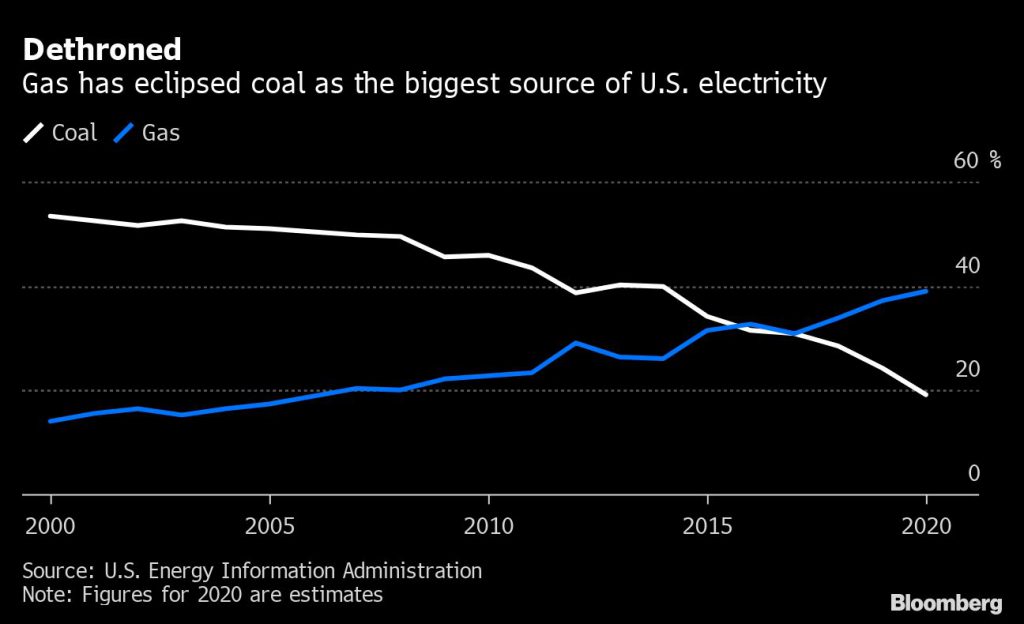

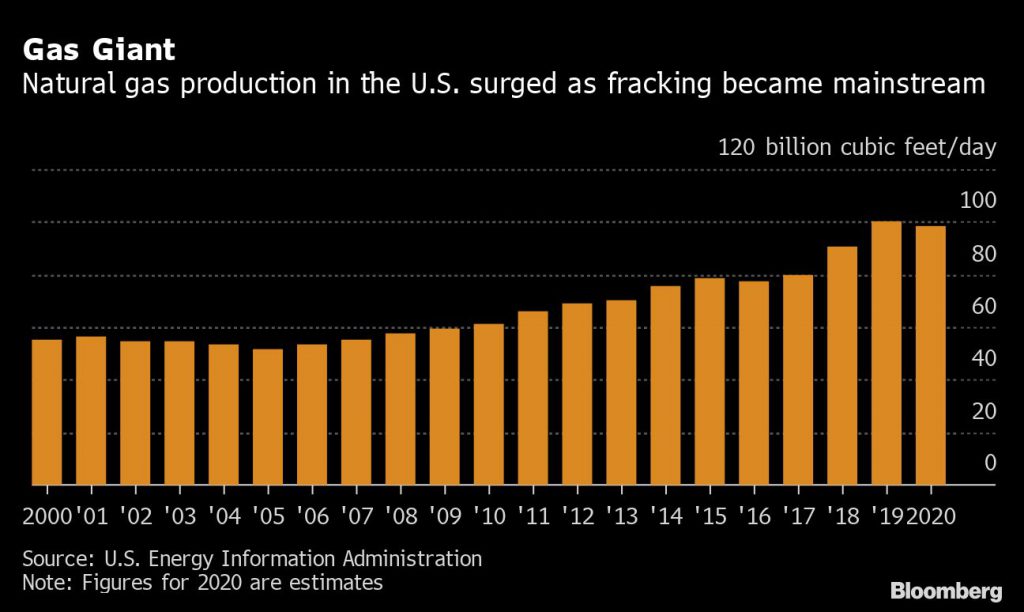

Gas, like coal a decade ago, is facing economic headwinds. While it’s still the nation’s dominant fuel source, it’s less competitive against renewables than it used to be. Solar and wind are now cheaper than gas-fired power in two-thirds of the world, according to BloombergNEF. In the U.S., top wind projects already produce electricity for less than natural gas and, by 2030, renewables are expected be cheaper on average than the fossil fuel, BNEF said in an April report.

The right combination of federal policies could easily push gas out of the power mix by 2035 or earlier.

“This transition is going to happen more quickly than people thought, just as the coal transition has happened faster than people thought it would,” said John Coequyt, the climate policy director at the Sierra Club.

To be sure, gas may reap some benefits from a Biden presidency in the near-term. Though his proposal to limit drilling on federal lands could trim production, tighter supplies could lift prices, potentially making gas exports more profitable. Similarly, a thaw in U.S.-China relations could give exporters greater access to a major world market.

But higher prices would have the opposite effect in the power sector, where cost is key. Gas-fired electricity generation is already expected to fall 5.7% this winter compared to last year simply because gas prices are higher this season, according to Energy Information Administration projections. And that’s despite forecasts for a colder winter, which would increase electricity demand.

The economics put gas in a roughly similar position as coal in the years before President Barack Obama took office.

In coal’s case, Obama hastened its decline by imposing new environmental regulations that made coal plants more costly to operate – notably the 2012 Mercury and Air Toxics Standards that limited toxic emissions from plants, and the 2015 Clean Power Plan that curbed carbon emissions.

A Biden administration could take a similar tack, imposing new — and more stringent — limits on greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. He could also reinstate and possibly strengthen Obama-era rules curbing methane leaks from gas infrastructure, which were repealed by President Donald Trump. Both have the potential to drive up the cost of gas-fired electricity, without banning the fuel.

Most analysts agree that Biden wouldn’t explicitly go after the gas industry in the same way that Obama attacked the coal sector. Instead, Biden’s clean-energy policies would make it harder for gas to compete with wind, solar and other renewables.

“You might be able to adopt policies that at least give them a theoretical chance to survive, even if they’re going to make it much harder for them to survive,” said David Spence, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law.

| Biden’s Climate Toolbox |

|---|

| A combination of agency guidance, formal regulations and environmental reviews could dim gas’s prospects, though Biden hasn’t committed to every option: – Reinstating Environmental Protection Agency and Interior Department rules limiting methane emissions from wells – Imposing limits on greenhouse-gas emissions from power plants in the vein of the Clean Power Plan – Regulating fracking wastewater under the Safe Drinking Water Act – Halting sales of new oil and gas leases on federal lands and waters – Slowing the processing of drilling permits for federal leases – Stopping issuance of new gas export authorizations – Encouraging agencies, including the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, to give more weight to emissions when vetting gas infrastructure |

For now, there isn’t much pressure to close the gas plants already in service. “Existing gas plants will have a role to play for a while,” said Mark Dyson, a principal at the Rocky Mountain Institute. “They’re keeping the lights on while we build as much wind and solar as we can.”

And Biden’s proposal leaves the door open for utilities to continue using gas plants that are fitted with carbon-capture systems that trap emissions, said Jonathan Elkind, senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

In Thursday’s town hall, Biden stressed the importance of embracing “new technologies,” including carbon capture, as a way to achieve a carbon-free electricity sector while still using some natural gas.

Still, utilities might not want to make that kind of investment when the price of renewables continues to fall.

“A lot of the path to net-zero by 2035 for power will come from energy efficiency gains, a lot from renewables, and that will squeeze out fossil fuels eventually,” said Katie Bays, an analyst with Sandhill Strategy in Washington.

Already, local jurisdictions are moving away from gas in pursuit of their own climate goals. Cities across California have moved to ban natural gas use in homes, while New York blocked a proposed $1 billion pipeline that Governor Andrew Cuomo. Opposition by environmental groups even drove Dominion Energy Inc. to cancel a major pipeline project before selling most of its gas operations in July.

Utilities are also preparing for a gas-less future. Besides building renewables, power giants NextEra Energy Inc. and Entergy Corp. are among companies investing in gas turbines that can transition to running on 100% renewable hydrogen.

Still, many doubt whether it’s even possible to achieve a carbon-free power grid in 15 years, which is a more ambitious goal than California and New York have set for themselves. Transforming the electric grid would be both costly and complicated and analysts caution against taking the plan too literally.

To pay for it, Biden has proposed an increase in the corporate income tax rate to 28% from 21% as well as using stimulus money. But that would require congressional approval, a tall order if Republicans retain control of the Senate.

Nevertheless, the push for decarbonization reflected in the Biden plan presents a real, long-term threat to natural gas as a source of electricity.

“There would be a huge downside risk for gas demand,” said Carlos Torres Diaz, head of gas and power market research at Rystad Energy AS, in Oslo. “Even if we don’t get to zero.”

(By Will Wade, Gerson Freitas Jr. and Jennifer A. Dlouhy)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments