BHP’s return to Argentina marks new hope for untapped copper mines

A new incentive regime for mining in Argentina is attracting major players such as BHP, who are starting to eye the South American country as the world’s next frontier for copper, more than half a dozen mining industry officials told Reuters.

BHP’s investment last month marked the company’s first foray into mining in Argentina in two decades. It teamed up with Canada’s Lundin Mining in the $3.25 billion buyout of Filo Corp, with the aim of developing two copper mines along the Andes mountains bordering Chile.

The re-entry of one of the world’s biggest miners has spurred hopes of other copper producers to secure better valuations for their projects so they can access finance and jumpstart projects. Copper mining has floundered for decades in Argentina’s volatile economy.

President Javier Milei is aiming to light a fuse with a law passed in late June promising lengthy tax breaks for investments pledged in the next two years – a bid to allay investor fears and offset capital controls that some politicians dubbed instruments of torture.

The Incentive Regime for Large Investments, or RIGI, also guaranteed investors’ access to international dispute courts, rather than needing to go through slow-moving local courts.

The need to mitigate risk in volatile mining locations was thrown into the spotlight after Panama’s government last year forced First Quantum Minerals to shutter its massive mine after protests. The closure removed 1% of the world’s copper supply and sent shockwaves through the industry.

“Mining in Argentina is set for exciting growth following the country’s new RIGI investment protection regime. It is great news for our Taca Taca project in Salta,” Tristan Pascall, First Quantum’s CEO, told Reuters.

He added that its planned mine in Salta province could potentially deliver 250,000 metric tons of copper a year.

He noted Argentina could be opening up for the right investors to potentially come on board depending on the type of financing that is needed.

Still, Milei faces an uphill battle to right the economy, and analysts say investors will need to contend with the world’s highest inflation, contracting GDP and worsening poverty.

“Argentina’s economy still faces many challenges, and foreign companies will remain subject to financial volatility,” said Christian Perlingiere, the Southern Cone specialist at business consultancy Control Risks.

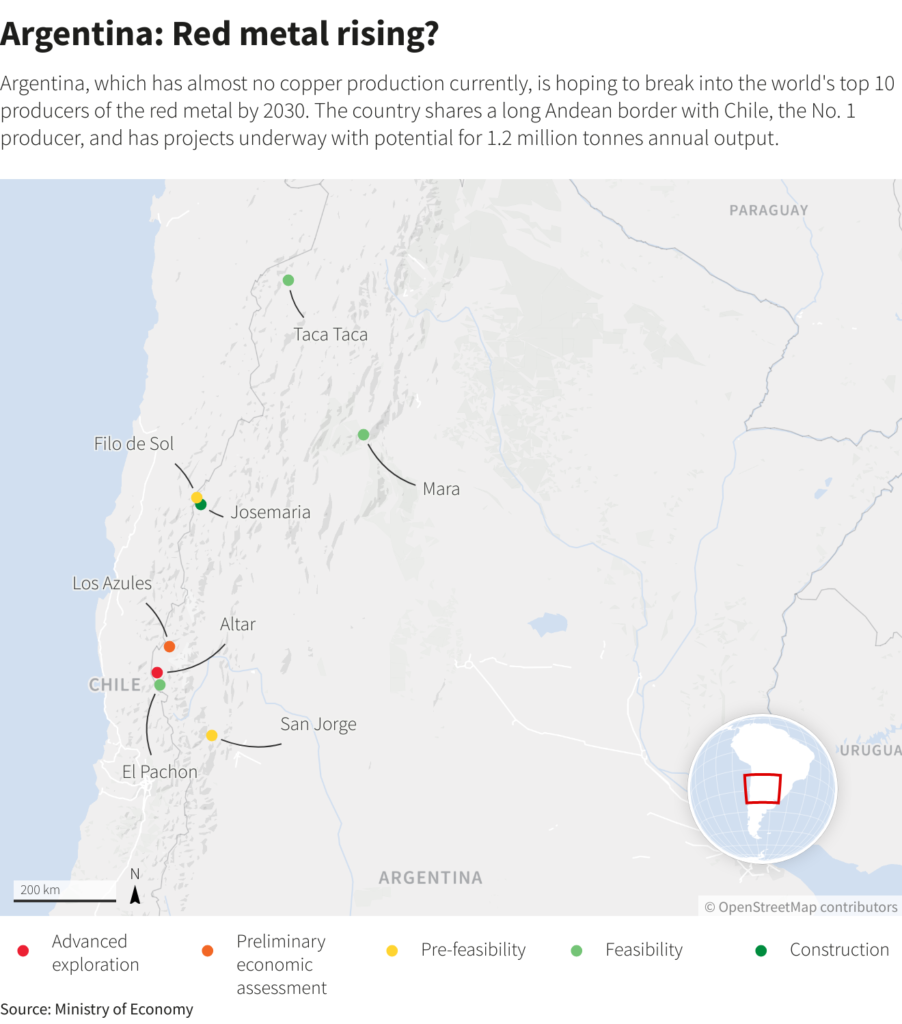

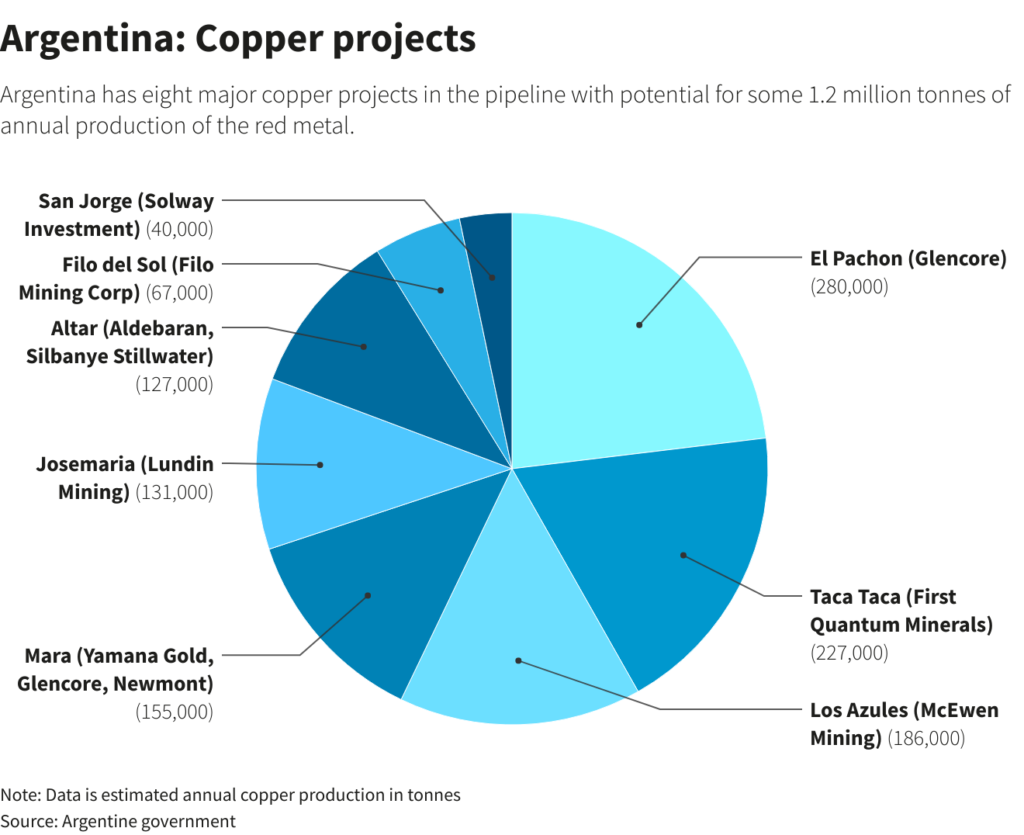

Although Argentina has no current copper production, eight major projects are in various stages of development in the mountainous north.

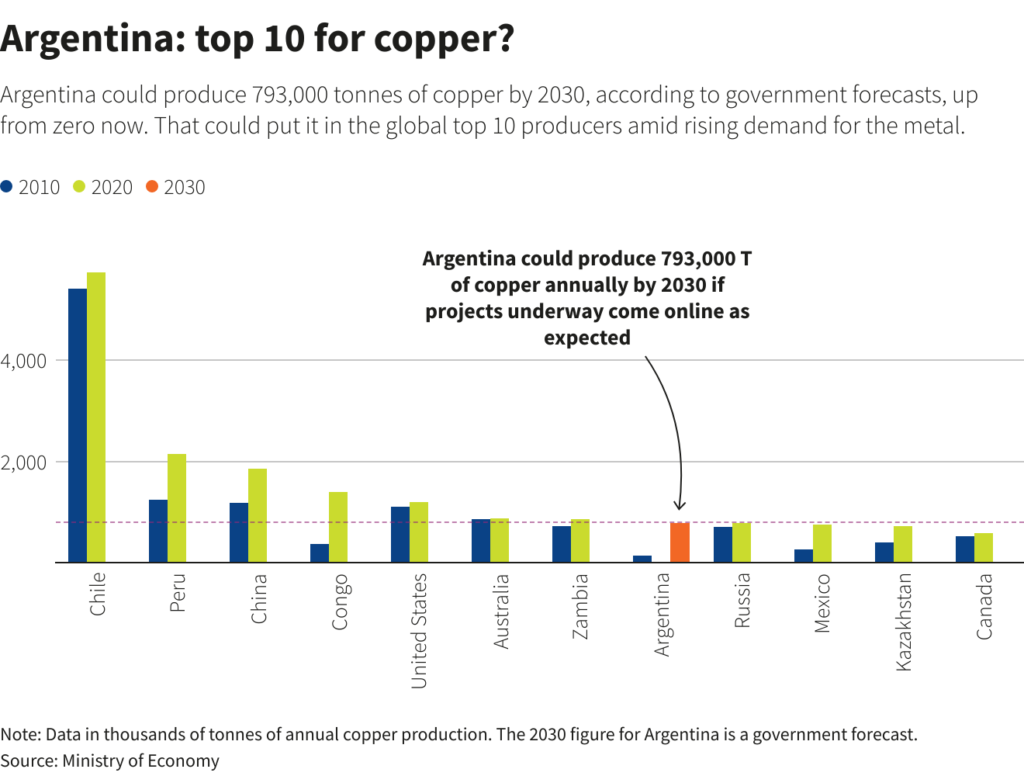

That means the country has a potential pipeline of projects that the government says could come close to the output levels of Australia and Zambia by the end of the decade, although still far behind top producer Chile.

Javier Roberto, who oversees the early-stage Altar project in San Juan province for Aldebaran Resources, expects BHP’s vote of confidence to help it secure financing – even though Altar is unlikely to qualify for Milei’s investment perks because it is still in its exploration phase.

“Many things we were waiting for, the big investments from abroad, are starting to crystallize,” Roberto said.

He said the company has begun to seek financing to push the project ahead up to the pre-feasibility stage in 2026, beginning with conversations with three major current investors, while looking at options such as issuing shares or bringing on an investment bank.

“We’re feeling out, so to speak, some of the players in the market,” he said.

The local unit of Canada’s McEwen Mining, backed by carmaker Stellantis and Australian miner Rio Tinto, are also poised to benefit.

“We do think our valuation will go up considering we are building our Los Azules copper mine geographically in a much easier location compared to Josemaria-Filo,” said Michael Meding, vice president of McEwen Copper, referring to the two mines to be developed by BHP and Lundin.

The company is discussing its next funding round with partners ahead of a 2029 production target.

Milei’s reforms, part of his tough-medicine drive to fix Argentina’s stunted economy, come as mining M&A heats up globally. Larger copper miners are targeting smaller rivals, keen to stockpile the red metal that is expected to be in huge demand for the global clean energy transition and artificial intelligence technologies, which will need to be powered by high capacity data centers.

Glencore CEO Gary Nagle, speaking in the company’s latest results call in August, highlighted Milei’s reform as a driver for more deals.

“Argentina is the next frontier for copper growth, no question,” he said. The company plans to spend up to $400 million in the next two years at its Argentina projects, Mara and El Pachon, but has not said when production might start.

Chasing incentives

Under Milei’s RIGI incentive scheme, miners are promised 30 years of tax credits, lighter customs duties and a progressive easing of capital controls.

Lundin chief operating officer Juan Andres Morel told Reuters the scheme’s passage into law was a catalyst to finalize the BHP deal, slated to close early next year.

From there, the joint venture will look at investment needs and financing options for Josemaria, the most advanced copper project in Argentina, he said. BHP did not respond to a request for comment, but noted “improving investment conditions” in Argentina when it announced the Lundin deal.

If Josemaria and several other major projects come online, Argentina could produce 793,000 metric tons of copper a year by 2030, according to mining ministry projections in a government report last year.

The Mining Ministry has not yet updated its forecast.

Copper exports by that time could reach between $5 billion and $10 billion, depending on how many projects are successful, according to a separate government report this year.

Developers will have to move fast to make a play for RIGI perks. Once a mining project is approved, it must spend 40% of its declared investment in two years, with the possibility for a one-year extension.

Morel acknowledged the timeline was demanding.

“It’s good and bad, of course. It gives us some sense of urgency to move forward with Josemaria,” Morel said. The initiative includes building roads and power lines, and securing water.

Some analysts cautioned against putting too much hope into incentives for the long-term, given potential for political change, as well as the rocky macroeconomic environment.

“RIGI definitely helps C-Suites feel warm and fuzzy towards Argentina again, but I wouldn’t base my investments solely on them,” said Christopher Ecclestone, a mining strategist at advisory firm Hallgarten & Company.

Milei’s four-year term ends in 2027 and he can seek re-election. The far-right libertarian has so far remained relatively popular, though risks losing support with an austerity plan that includes slashing the size of government, trimming back fuel and transport subsidies, shutting state institutions, and auditing welfare schemes.

Mining projects in general are often subject to environmental concerns and community protests, issues that have dogged miners around the world from Serbia to Panama.

Glencore’s Mara project in Catamarca province encompasses one of Argentina’s only copper mines ever to be operational, Bajo de la Alumbrera. It was forced to shutter over an environmental dispute in 2018, and never reopened.

(By Daina Beth Solomon, Divya Rajagopal, Lucila Sigal and Pratima Desai; Editing by Veronica Brown and Claudia Parsons)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

kunj gaur

like your site