BHP bombshell puts South African mining in a hole

BHP has put South Africa and its mining sector on the spot. The $140 billion Australian group’s ambitious swoop on rival Anglo American would see one of the Rainbow Nation’s most familiar companies largely withdraw from the country more than a hundred years after it was founded. The question is whether the government in Pretoria can stop the $39 billion transaction – and whether it should.

South African officials have so far given BHP’s proposal a mixed reception. Gwede Mantashe, the country’s mining minister, told Bloomberg he “wouldn’t support” the deal. But President Cyril Ramaphosa’s spokesperson described the approach as “normal market activity”.

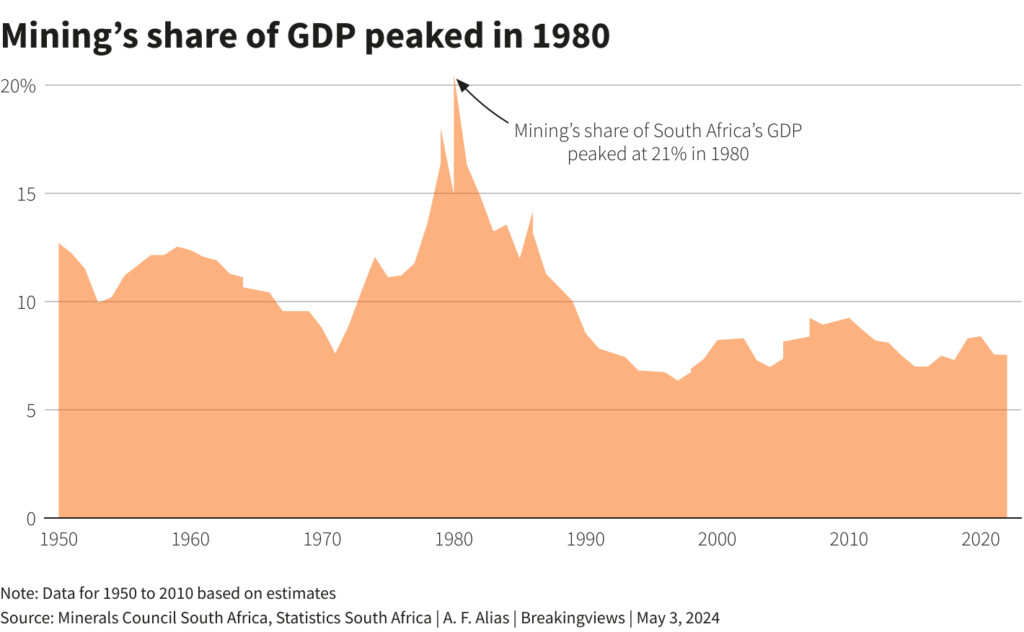

In reality, Pretoria has a host of reasons to be awkward. South African mining is in decline: as a contribution of GDP it has fallen from 21% in 1980 to 7.5% in 2022. The country’s platinum, diamonds, coal and iron ore are not integral materials to the all-important energy transition. Corruption scandals at state utility Eskom and issues at freight carrier Transnet have led to frequent electricity blackouts and problems for miners trying to get shipments out of the country.

Anglo, which was founded in Johannesburg in 1917, has tended to be more of a help to the government than a hindrance in dealing with these challenges. The London-listed group, currently run by CEO Duncan Wanblad, has invested $6 billion in its home country in the last five years, including in educational projects. It also acts as a reliable counterparty in the mining sector’s frequent labour disputes.

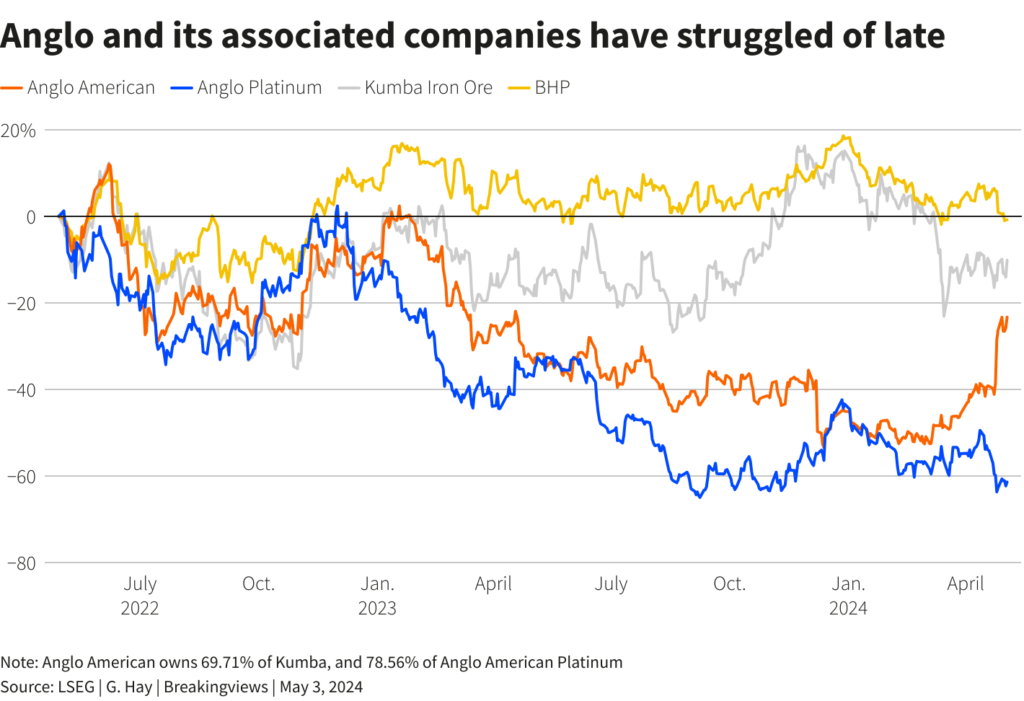

BHP chief executive Mike Henry’s planned deal would take a crowbar to this arrangement. The Australian group wants Anglo to spin off its controlling stakes in local mining companies Anglo American Platinum (Amplats) and Kumba Iron Ore, which have a combined equity value of about $13 billion. Except for nuggets like the domestic operations of its De Beers diamond unit, Anglo would effectively check out of South Africa.

Henry has travelled to South Africa to make his case. Yet his initial brusque approach is striking because prominent political figures like Mantashe already had reasons to dislike BHP. After merging with domestic mining giant Billiton in 2001 the “Big Australian” spun off most of its South African assets into a new company called South32 in 2015. It did so under a cloud caused by revelations that Billiton had a secret, decades-long contract to get cheap electricity from Eskom for its aluminum smelters. While stressing he was not expressing an official government position, Mantashe told the Financial Times last month that the BHP Billiton merger “never did much for South Africa” and that his country’s experience with BHP was “not positive”. Throw in the fact that South Africa is holding national elections on May 29, and there’s a fertile backdrop for opposing a foreign takeover.

The government also has the means to do so, even though the country’s Public Investment Corporation owns only 7% of Anglo. South Africa’s Competition Commission must approve all mergers and demergers and can use controversial “public interest” powers to nix a transaction even if it lacks antitrust grounds.

Yet South Africa also has good reasons to be more even-handed. While the share of non-resident holdings of domestic government bonds has fallen from 40% five years ago to 25% now, the country would be ill-advised to spook foreign investors grappling with elevated global interest rates. Blocking a valid deal on spurious grounds may do just that. Throwing up regulatory roadblocks could also prompt other investors in South African assets to fret they might not be able to get their money out.

There’s a smarter way for Ramaphosa to play the situation. Anglo has long suffered from a stock market discount due to its South African roots: breaking up the company could unlock at least $10 billion more than the $39 billion equity value implied by Henry’s approach, a Breakingviews sum of the parts suggests. Shareholders may therefore resist BHP’s current proposal.

Only about a third of Anglo shareholders are domestic South African investors. So if the company spins off Amplats and Kumba, as BHP wants, the value of those two units may well drop. Investors previously hoped that Anglo might at some point buy out minority shareholders at a premium. Meanwhile, overseas investors may be unwilling to hold shares listed in South Africa. In this scenario, assets which account for roughly a third of the value of BHP’s proposal might actually be worth a lot less.

South Africa could also use the threat of its own veto to extract concessions from BHP. Even though the Competition Commission ultimately waved through previous international swoops on local assets, like brewer Anheuser-Busch InBev’s $106 billion acquisition of SABMiller in 2016, it only did so after receiving promises on jobs, local production, long-term commitments to South Africa and payments to the farming sector. Spinning off Anglo’s South African assets could trigger a $2 billion capital gains tax payment to the government; with some other goodies the authorities might look more favourably on BHP’s proposal.

South African politicians may also open the door to a bid from another mining group like Glencore. The $70 billion Swiss miner-trader is studying an approach for Anglo, Reuters reported on Thursday citing two sources. Its smaller size means Anglo shareholders would hold a larger proportion of the combined group in an all-share deal. Glencore also has strong South African connections and may want to keep Kumba and market its iron ore. Boss Gary Nagle could therefore propose a merger which would be more acceptable to South Africa.

Anglo American’s South African heritage weighs on the company’s value. That’s one of the reasons BHP swooped. A takeover will not solve South African mining’s wider headaches, even if a buyer agrees to hold on to Amplats and Kumba. Any new owner would seek ways to unlock the value of Anglo’s assets in ways Pretoria might not like. Still, while BHP has put South African mining on the spot, the government has the power to do the same to any buyer.

Context news

Commodities group Glencore is studying an approach for Anglo American, Reuters reported on May 2 citing two sources.

Glencore has not yet approached Anglo, one of the sources said. The discussions are internal and preliminary at this stage and may not result in an approach, the source added. A Glencore spokesperson said the company did not comment on market rumour or speculation.

South Africa’s independent antitrust authority, the Competition Commission, requires “a mandatory merger notification … where any transaction involves the change of control over the business of Anglo in South Africa”, the Financial Times reported on May 3.

The commission usually assesses whether a deal would reduce domestic competition, and whether it is justifiable on “public interest” grounds. This includes the impact on a sector, on jobs, on historically disadvantaged South Africans, and the ability of industries to compete globally, spokesperson Siyabulela Makunga told the FT.

(By George Hay; Editing by Peter Thal Larsen and Oliver Taslic)

Read More: What’s Anglo worth? For now it’s less than the sum of its parts

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments