Base metals analysts turn cautious after stellar rally

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Put the champagne back on the ice.

After a super-charged rally over the second half of 2020 base metals may struggle to notch up further price gains in the short term.

While the demand recovery is expected to spread from China to the rest of the world this year, analysts participating in last week’s Reuters base metals poll were cautious, expecting high inventories and rising supply to keep a lid on prices.

All the base metals with the exception of tiny tin are expected to register supply-demand surpluses this year and next

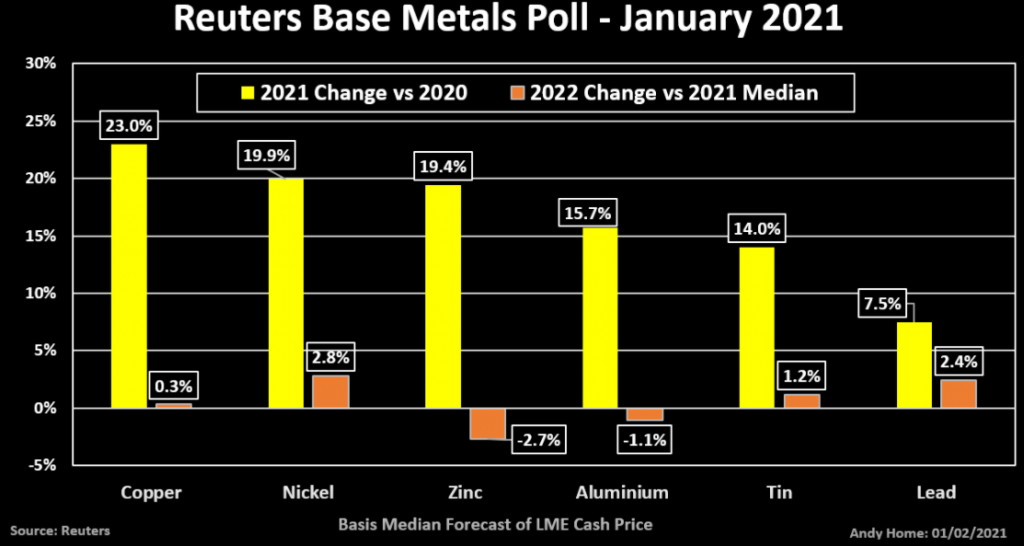

Median forecasts for all the base metals are significantly up on last year, which is unsurprising since prices collapsed in the first quarter as the pandemic locked down China’s – and then everyone else’s – manufacturing sector.

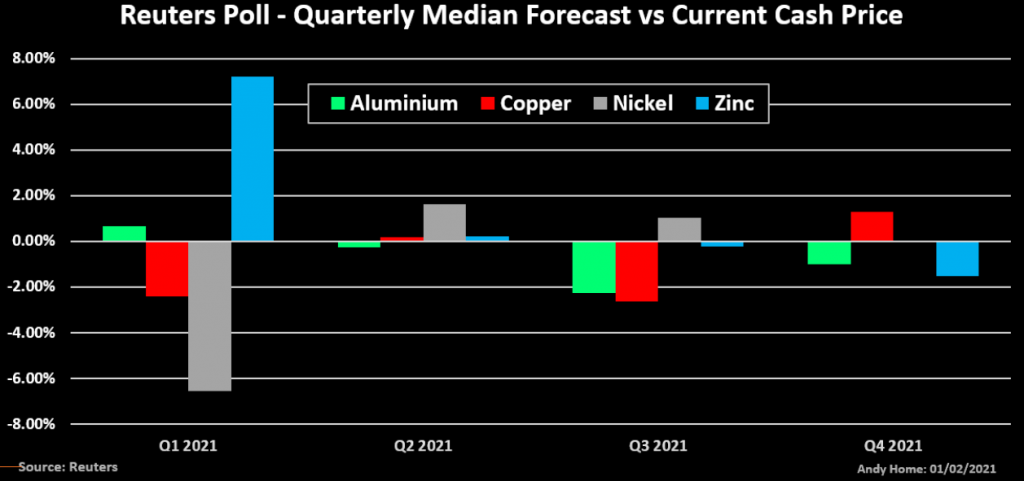

But the subsequent rebound has been so sharp that today’s prices are already higher than median expectations for the year, implying a retreat from the peaks.

Curbing bullish enthusiasm

The London Metal Exchange index has bounced by 48% from its March 2020 lows.

Copper has led the charge and this year’s forecast average price is $7,600 per tonne, up 23% on last year’s cash average.

However, with LME copper now trading around $7,800, it is clear that analysts feel much of the good news is priced in.

Copper is expected to consolidate over 2021. Quarterly forecasts fluctuate only a couple of percentage points around the current price.

Perhaps more surprisingly, analysts are equally wary of next year’s outlook with a median forecast of $7,625 per tonne, also below current market levels.

Expectations for the rest of the base metals pack are similarly modest with prices largely expected to remain close to current levels over the course of 2021 before diverging more significantly next year.

Nickel, for example, is projected to rise by 20% to $16,535 per tonne in 2021 relative to last year but by only a further 3% to $17,000 in 2022. Friday’s cash settlement price was $17,727.

Some further price appreciation is also expected for tin and lead over the next two years but here too prices are already trading above forecast levels. Friday’s cash tin price of $23,657 was above even the highest forecast of $22,125 for this year and $22,000 for next year.

The divergence will come in the zinc and aluminum markets. Prices of both are expected to weaken over the course of 2020. Median 2022 forecasts of $2,635 for zinc and $1,950 for aluminum represent declines of 3% and 1% respectively from this year’s median forecasts.

China slowdown fear

The collective view that base metals will consolidate around current levels over coming quarters is rooted in views about what happens in China this year.

Massive stimulus last year, pumped through the usual channels of construction and infrastructure, boosted demand and prices for metals.

However, there is a broad consensus that Chinese policy-makers will steadily turn off the spending taps this year, dulling growth in the world’s biggest user.

Capital Economics is one of many expecting China to remain the dominant force on pricing. The research house forecasts industrial metal prices falling over the second half of 2021, dragged down by China.

It expects a “notable slowdown” in China’s credit growth, including tighter restrictions on property lending, will weigh on economic activity. (“2021 to be a year of two halves”, Jan. 28 2021)

Also curbing bullish spirits is concern about the amount of surplus metal accumulated during manufacturing lockdowns last year. Much of it has been sitting in hidden off-exchange storage. But as the zinc market has just discovered, the sudden appearance of previously unreported stock can be a harsh reality check.

Moreover, supply should also stage its own coronavirus recovery after multiple mine closures last year stressed supply chains.

Surplus markets

All the base metals with the exception of tiny tin are expected to register supply-demand surpluses this year and next.

Even copper, with its bullish market optics of massive Chinese imports and low visible inventory, is expected to see excess supply of 31,000 tonnes in 2021 and 20,000 tonnes in 2022.

True, those projections are lower than the last quarterly poll and, also true, the market balance forecasts span a wide range of expected outcomes, but the general thinking is that recovering supply will broadly match recovering demand.

Forecast surpluses for other metals such as aluminum and zinc are bigger, which is why analysts are unconvinced either can hold recent gains over a two-year horizon.

Has even tin, arguably the base metal least susceptible to speculative excess, outrun its own fundamentals?

Meanwhile, a cumulative supply excess of 112,500 tonnes in the nickel market over the next two years will disappoint the battery metal’s many bull fans.

Tin is the stand-out exception.

Not many analysts hazard a market balance forecast for tin, but of the five that did for this year four expect a supply shortfall. Three out of four submitting an estimate for next year predict a second year of deficit.

The question remains, though: has even tin, arguably the base metal least susceptible to speculative excess, outrun its own fundamentals?

Hitting the pause button

This poll suggests a collective pause for breath by an analyst community that was initially caught out by the strength of last year’s price recovery.

Few would now dispute the bigger emerging bull narrative for industrial metals, one centred on the demand boost created by the global shift towards decarbonisation.

Not everyone, though, seems ready to embrace claims by super-bulls such as Goldman Sachs that the commodities sector is on the cusp of a new supercycle.

Or at least not yet.

It’s the old sort of cycle, the Chinese one, that is top of most metals analysts’ minds right now.

Last year’s recovery in China’s manufacturing activity was breath-taking. So too have been the country’s imports for metals such as copper and aluminium.

Metals markets have been here before. Past experience suggests China’s authorities will move fast to damp down any stimulus excess and metal prices will retreat when they do so.

The supercycle and the champagne, it seems, are on hold for now.

(Editing by Edmund Blair)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments