Australian alumina ban will squeeze Rusal and aluminum

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Australia’s decision to ban exports of alumina to Russia tightens further the raw materials squeeze on Russian aluminum giant Rusal.

The company’s four million tonnes of smelter capacity each year process eight million tonnes of alumina, which sits between bauxite and refined metal in the aluminum production chain.

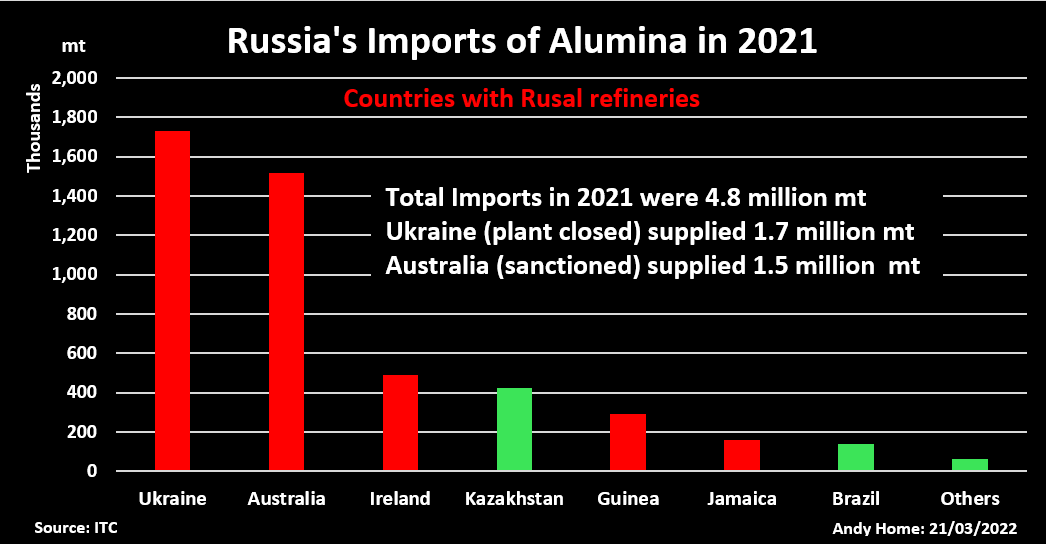

Rusal’s domestic alumina plants accounted for only 37% of its smelter needs last year. The balance was imported. The top two suppliers were Ukraine, where Russia’s invasion has closed Rusal’s Nikolaev refinery, and Australia.

The company said it is “currently evaluating” the loss of its number two raw material supplier but the market has already reacted to the potential resulting loss of Russian metal.

London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month aluminum jumped more than 5% at its opening to $3,554 per tonne on Monday morning and was last trading around $3,545.

Raw materials squeeze

Rusal has so far escaped direct Western sanctions thanks to the deal that was done to lift US sanctions in 2019. Rusal’s oligarch owner Oleg Deripaska remained blacklisted but Rusal was excluded after he reduced his controlling stake in the EN+ holding company.

That may just have changed, though.

The Australian government’s ban, expedited to stop a Russian-bound alumina shipment leaving this week, doesn’t explicitly name Rusal but it is a de-facto sanction on the company that dominates Russian aluminum production.

The status of Rusal’s 20% stake in the QAL refinery in Queensland is highly moot since it now can’t export its offtake share and its partner Rio Tinto is committed to disengaging from all Russian joint ventures.

Rio has already suspended a tolling arrangement with Rusal’s Aughinish alumina refinery in Ireland, forcing the Russian producer to redirect bauxite shipments from its Guinea mines.

Such self-sanctioning limits Rusal’s room for maneuver in terms of replacing lost Australian feed.

The sea-borne alumina market is dominated by Rio Tinto, US producer Alcoa and Norway’s Hydro. All three have said they will reduce exposure to Russia or, in the case of Hydro, not enter into new contracts with Russian entities.

The biggest question mark of all hangs over the Irish refinery, Rusal’s largest overseas alumina plant with production last year of 1.9 million tonnes.

Only a quarter of its output flowed to Russia in 2021, meaning there are plenty of potential to redirect shipments from Europe to Russia.

The Irish government is understandably keen to keep Aughinish operating but the European Union is already extending sanctions into the metals arena with a ban on Russian steel imports and will have no doubt noted Australia’s upping of the sanctions ante.

With or without its Irish lifeline, however, Rusal is facing a raw materials squeeze.

China may be its answer but China has been importing significant amounts of alumina in recent years to keep up with demand.

Even assuming the political will to supply Rusal with alumina, the market incentive may not be there, given expectations of rising domestic alumina demand as Chinese smelters lift output after an easing of power controls.

Aluminum squeeze

The aluminum price’s reaction to news of the Australian ban tells you how concerned it is about the potential loss of Russian metal production.

As the Australian Foreign Ministry helpfully pointed out in its statement, “aluminum is a global input across the auto, aerospace, packaging, machinery and construction sectors”.

This is a real problem if the West is losing access to Rusal’s four million tonnes of annual production.

The aluminum supply chain was already creaking. Power-efficiency constraints have turned China, the world’s largest producer, into a net importer of unwrought aluminum to feed its massive downstream products sector.

Production at Europe’s power-hungry smelters has been falling due to high energy prices, a phenomenon that has only gotten worse since Russia launched on Feb. 24 what it calls a “special military operation” to disarm and “denazify” Ukraine.

Visible aluminum stocks have been sliding steadily for over a year to plug the supply-chain gaps. Total LME inventory stands at 704,850 tonnes, the lowest level since 2007.

The global aluminum market is tight, the Western European market particularly so, both because of the recent smelter cuts and its dependence on Russian supply.

Europe accounted for 41% of Rusal’s sales last year and disruption to Russian shipments will only widen the region’s existing supply deficit.

Moreover, Rusal is a critical supplier of “green” – low-carbon – aluminum from its hydro-powered Siberian smelters.

While global aluminum trade flows may eventually adjust in the wake of the Ukraine crisis, automakers keen to use only the greenest metal in their next-generation electric vehicles may find a far more challenging supply landscape.

Tightening the sanctions screw

The complexity of Rusal’s raw material supply web was exposed back in 2018 when U.S. sanctions set off a chain reaction that spanned Ireland, Guinea and Australia and ended with European car companies lobbying the European Commission to intercede with the United States.

Those US sanctions were a bolt from the blue.

This time around the effect has so far been more incremental as supply, logistics and financing avenues dwindle due to self-sanctioning.

The Australian government’s move to add alumina to the sanctions list marks a significant escalation in this process.

Critical for Rusal and the aluminum market alike is whether other countries follow suit.

(Editing by Emelia Sithole-Matarise)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments