Australia is quitting coal in record time thanks to Tesla

Like so much in our modern era, Australia’s high-stakes gamble on renewable energy starts with an Elon Musk Twitter brag.

South Australia’s last coal-fired power plant had closed, leaving the province of 1.8 million heavily reliant on wind farms and power imports from a neighboring region. When an unprecedented blackout caused much of the country to question the state’s dependence on clean power, Tesla boasted — on Twitter, of course — that it had a solution: It could build the world’s biggest battery, and fast.

“@Elonmusk, how serious are you about this,” replied Australian software billionaire and climate activist Mike Cannon-Brookes. “Can you guarantee 100MW in 100 days?”

Musk responded: “Tesla will get the system installed and working 100 days from contract signature or it is free. That serious enough for you?”

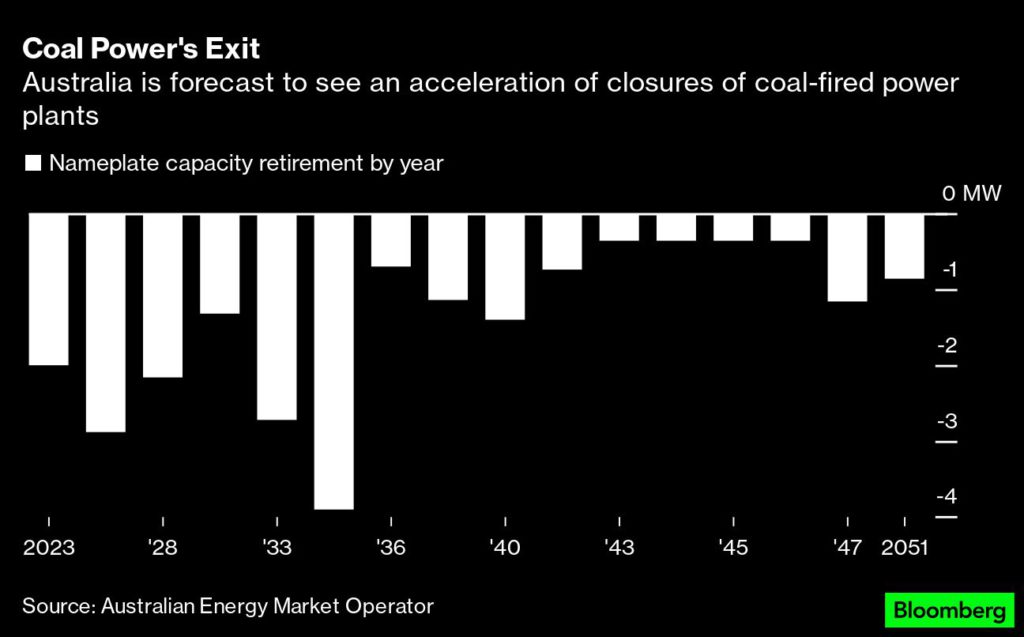

To the astonishment of many, Tesla succeeded, and today, almost seven years later, that battery and more like it have become central to a shockingly rapid energy transition. By the middle of the next decade, major coal-fired power stations that generate about half of Australia’s electricity will shut down. Gas-fired plants are being retired, too, and nuclear power is banned. That leaves solar, wind and hydro as the major options in the country’s post-coal future.

“It’s really a remarkable story,” said Audrey Zibelman, the former head of the Australian Energy Market Operator, or AEMO, the agency that runs the grid, and now an adviser to Alphabet Inc.’s X. “Because we’re not interconnected, we’ve had to learn to do it in a much more sophisticated way, where a lot of other countries will go once they’ve shut down their fossils.”

It may be Australia’s biggest power buildout since electrification in the 1920s and 30s. And, if successful, could be replicated across the 80% of the world’s population that lives in the so-called sun belt — which includes Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, India, southern China and Southeast Asia, says Professor Andrew Blakers, an expert in renewable energy and solar technology at Australian National University. That, in turn, would go a long way to halting climate change.

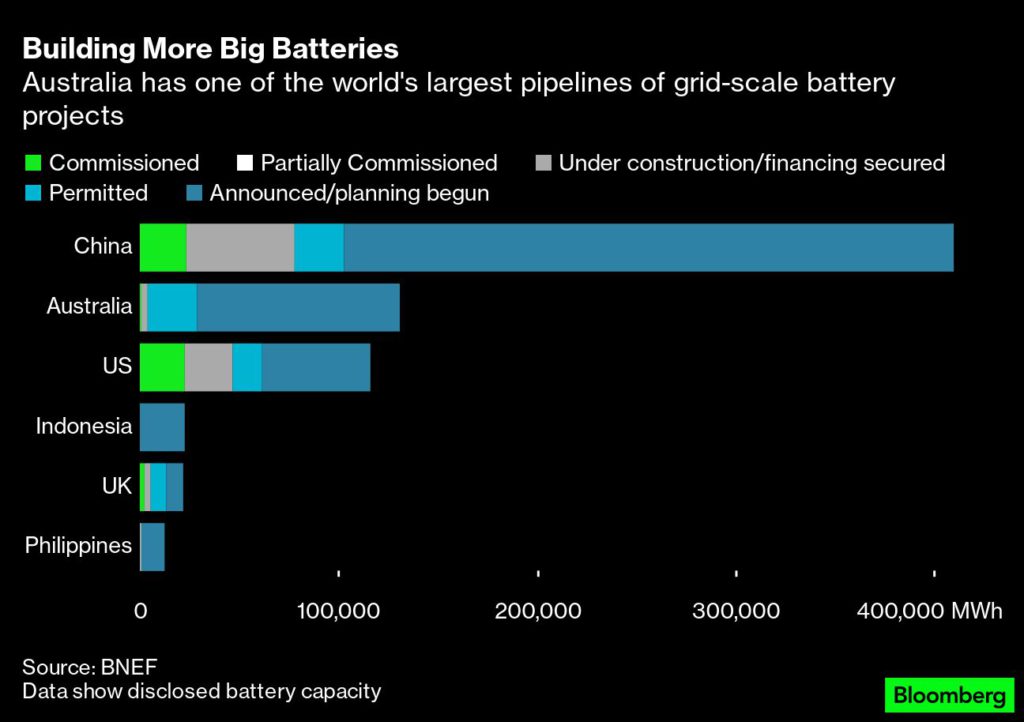

Building battery storage is just one critical piece of the national project, and AEMO and others are worried coal plants will shut before there’s enough additional electricity supply. Australia needs to increase its grid-scale wind and solar capacity ninefold by 2050. Connecting all that generation and storage into the grid will require more investment.

Overall, the cost could be a staggering A$320 billion ($215 billion), and the money is starting to flow: Brookfield Asset Management Ltd., Macquarie Group Ltd., and billionaires Andrew Forrest and Cannon-Brookes have all been involved in headline-grabbing energy deals in recent months. New government support for renewables has also improved investor sentiment, according to the Clean Energy Investor Group, which includes project developers and financiers.

Australia’s great coal switch-off is coming. New South Wales, the most populous state and home to Sydney, will lose one massive plant this month, followed by Eraring, the country’s largest, in 2025. Victoria, the second most populous state, saw a major site shuttered in 2017. Next up is Yallourn Power Station, which dates back more than a century and is scheduled to close in 2028.

“I’m never going to say keep a coal plant open,” said Greg McIntyre, head of the Yallourn plant, a two-hour drive east of Melbourne. “But you’ve got to be realistic about what you’re switching off. Because with these plants, once you’ve switched them off, you can’t switch them on again.”

Until recently Australia was a climate laggard. A brief carbon tax was scrapped in 2014, it had no electric vehicle policy, and a 2030 emissions reduction target of just 26% to 28% below 2005 levels. Through the early 2020s, politicians routinely downplayed the risk of climate change — former prime minister Tony Abbott famously dismissed climate science as “absolute crap.” His treasurer and an eventual successor, Scott Morrison, once brought a lump of coal into parliament to taunt his pro-climate adversaries.

But while Canberra politicians ignored the energy transition, Australians were installing solar panels at record speed. China-made solar panels were cheap, and legacy government rebates sweetened the deal. From 2010 to 2020, the installed capacity of rooftop solar increased by 2,000%. Wind also grew rapidly. The market was awash in cheap electricity, and coal-fired suppliers soon found it harder to compete.

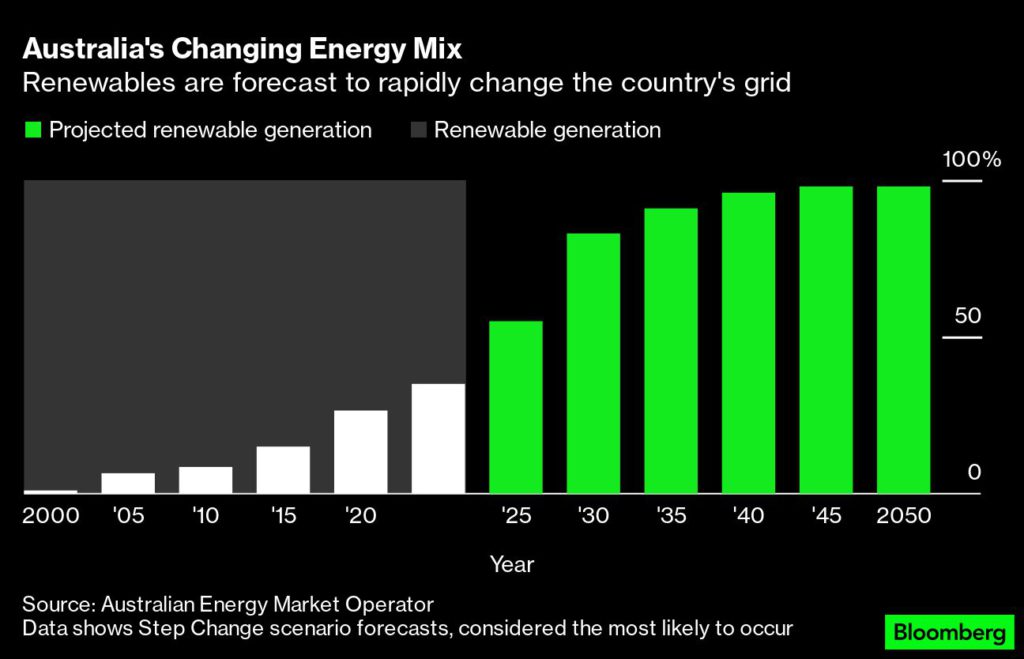

A coal plant in South Australia was the first early closure, in 2016. The next year, another retired in Victoria. The energy transition was underway, whether the government liked it or not. Of 15 key coal plants that power Australia’s main national grid, one-third are officially scheduled to shut by 2030. In less than 20 years, all of the country’s coal plants could be closed, the agency says.

With solar panels on the roofs of nearly one in three residential homes, Australia already has the highest penetration of rooftop solar per capita. By 2050, that proportion will grow to 65%, AEMO predicts, and account for more than a third of the country’s installed generation capacity.

Deployments of wind and large-scale solar farms will also surge. In total, renewables will supply 98% of electricity on Australia’s main grid from mid-century, up from around 35% today, according to AEMO.

The election last May of the center-left Labor Party has reassured the country’s financiers and investors about clean energy policy. Investment in renewables jumped 17% in 2022, mostly late in the year, after the new government announced emissions cuts and acted to enshrine them in law, according to the Clean Energy Council, an industry group.

“We are the global pathfinder for demonstrating that the rapid transition is possible,” Blakers said. “And it’s turning out to be much easier than most people think.”

Tesla’s grid-scale batteries are one part of the solution. They can absorb excess energy when it’s windy and sunny, then feed it back into the grid when it isn’t.

The original Tesla battery, owned and operated by France-based renewables group Neoen SA, is now a cornerstone of South Australia’s grid. It also served as a prototype for a much bigger installation: The Victorian Big Battery, comprised of 212 white boxes in a field west of Melbourne, capable of dispatching as much power as a giant coal turbine on a split-second’s notice.

Batteries can also solve a more technical problem. Coal generators do something wind and solar can’t: their giant spinning turbines provide inertia, which regulates the frequency of the entire grid. Without it, the network becomes highly unstable and the risk of blackouts soars.

“When there’s no more coal or gas running, you need to have someone who is setting the pace for the network, and batteries are able to do that,” said Neoen Australia Managing Director Louis de Sambucy.

But batteries can’t do everything. Specifically, they don’t generate power, and one of the biggest challenges is solving the winter problem known as the dunkelflaute, a period when weak sunlight and low wind combine with high power demand to drain power stores faster than they can be replenished.

“Batteries are very good at short term dispatch — fractions of a second, or minutes, or hours. The idea they can be good for days is not realistic,” says Tony Wood, energy program director at the Australia-based Grattan Institute think tank. What is needed, he says, is “deep storage” which can last weeks. He says currently the only feasible answer is natural gas, a fossil fuel.

Zibelman is more sanguine. She says zero-carbon technologies like pumped hydro, compressed air storage, and potentially green hydrogen plants can provide that deep, lasting storage without contributing to climate change. Blakers is even more bullish, arguing pumped hydro combined with batteries can provide all the storage Australia, and most of the world, needs.

The Australian government has backed pumped hydro, building the Snowy 2.0 project near Canberra that will use electricity to pump water from a lower reservoir along 27 kilometers (16.8 miles) of underground tunnels to an upper reservoir when demand is low.

When demand is high, it will release that water back down a parallel tunnel, passing through a turbine and generating electricity. This closed-loop system will be capable of storing enough energy to power 3 million homes for a week, according to the state-owned firm building the facility. There are also plans to tap the island of Tasmania for hydropower and feed the mainland via new undersea transmission lines.

That’s insufficient to respond to a severe dunkelflaute, says Wood. Australia will need many more. Meanwhile, Snowy 2.0 is over budget and has suffered construction mishaps. All that highlights the complexity of building the infrastructure needed to fill the gap left when coal plants retire.

Zibelman says demand management will also be key, for example, switching off unnecessary loads when supply is low. This will increasingly be done by artificial intelligence, she says.

But Abbott’s and Morrison’s Liberal National coalition, now in opposition, isn’t convinced renewables and storage are enough. After years of backing coal and gas, it has started campaigning to overturn the national ban on nuclear power, a proposal that the Labor government has rejected.

At the Yallourn plant outside of Melbourne, there’s no sign of the tectonic change ahead. Conveyor belts carrying mud-like brown coal arrive daily, with fuel dug out of a vast open-cut mine across the river. For nearly 100 years this is how Melburnians have got their power. It’s an anachronistic, carbon dioxide-spewing business, but it keeps the lights on in this city of 5 million people.

A few kilometers away, though, Yallourn’s owner, CLP Holdings Ltd.’s EnergyAustralia is building its own big battery, around the same size as Neoen’s Victorian Big Battery. It’s scheduled to come online in 2026.

After Yallourn, the state’s last two remaining coal plants a few kilometers away will also shut. In a few short years, Victoria will go from relying on coal for 70% of its electricity, to being entirely coal-free. Australia must get building, and fast.

(By James Fernyhough)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

4 Comments

Tom

Such a ridiculous headline, implying that battery storage is the main driver of Australia’s energy sector transit to renewables. Battety storage is a tiny percentage of overall generation, and a tiny part of current power firming efforts. It would be like saying “Australia is quitting coal in record time thanks to Bob’s 5kw solar panel install’. The change is so much larger than Tesla’s or even battery storage in generals miniscule contribution.

Steve B

Amazing how it only takes one early mover to start a major movement.

Jonty

Terrible idea to quit coal.

Tone

Why would anyone say it is bad to quit coal? Coal does so much damage to the environment and people’s health. Don’t forget it isn’t as cheap as Solar or Wind anymore.