Australia begins long road to retraining thousands of coal workers for clean energy roles

The sudden speed of the shift to clean power is forcing Australia, a global champion of coal and gas, to confront one of the energy industry’s biggest challenges — how to transition millions of fossil fuel workers to new roles in wind and solar.

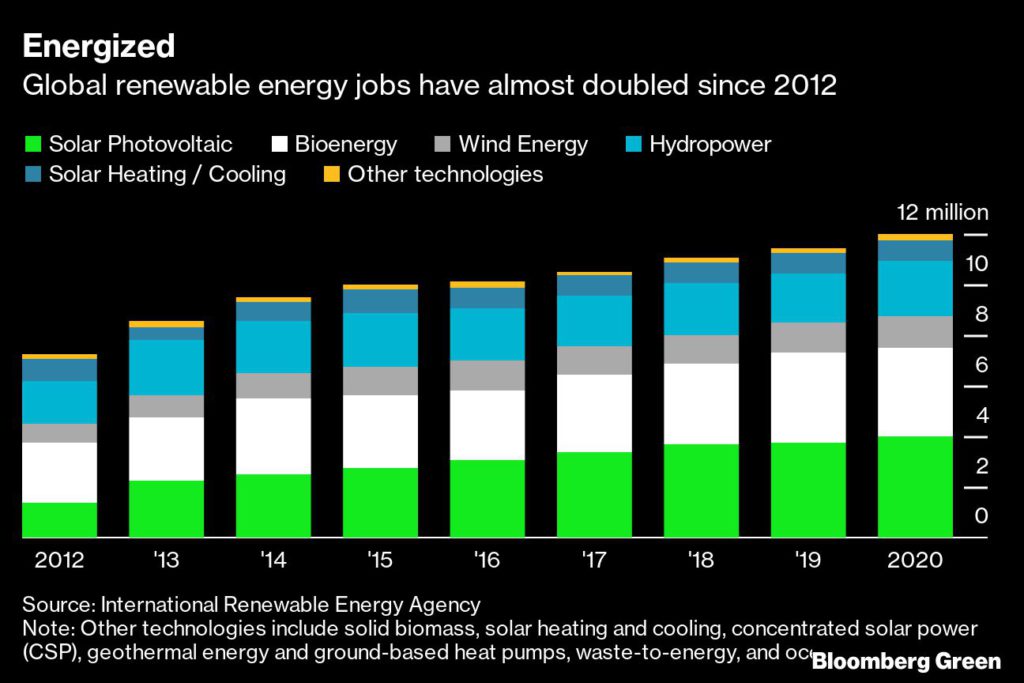

Clean energy could create more than 38 million jobs worldwide by the end of the decade and meeting that demand without a labor shortage requires accelerating efforts to not only lure new entrants, but also to create a clearer plan to retrain the industry’s veteran workforce as traditional fuel sources decline.

That’s a task getting underway in Australia, where coal’s supremacy is finally under threat from cheap clean power, and with lawmakers who once defended fossil fuels now trading promises over green jobs in campaigning ahead of a May national election.

“The light is just going on across governments and industry” that more investment in training is needed, with a lack of skilled workers already emerging for some existing projects and challenging plans to add more clean energy to help nations meet climate commitments, said Chris Briggs, research director at the University of Technology Sydney’s Institute for Sustainable Futures.

In the southeastern city of Ballarat, a key 19th Century gold mining hub, companies including Vestas Wind Systems A/S — the world’s biggest turbine manufacturer — have funded the country’s first wind power training tower, where students and ex-coal workers can use a 23-meter-high platform to acquire the expertise needed for roles in renewables.

“At the moment, with these skills, you have to fly them in from outside, or send Australians overseas,” said Duncan Bentley, a vice chancellor at Federation University, which hosts the site. The facility is the first local training institution that can provide a key safety qualification needed to work in the wind industry.

Renewables accounted for almost a third of the country’s electricity generation in 2021, double the share four years earlier, and utilities are bringing forward plans to retire coal-fired power stations years ahead of schedule.

About 10,000 coal jobs in Australian mines and power plants related to domestic electricity generation will be lost by 2036, according to Chris Briggs, research director at the University of Technology Sydney’s Institute for Sustainable Futures. More will surely also exit as coal exporters eventually shutter.

In the same period, around 20,000 to 25,000 new jobs will appear in the construction, maintenance and operation of renewable power, Briggs said.

Legislators, too, are starting to adapt. Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison won a 2019 election in part because his defense of fossil fuel jobs helped secure decisive support in coal communities. Ahead of May’s election — with his government trailing the opposition Labor Party in opinion surveys — he’s still supporting coal, but also touting prospects for workers to win new roles in clean hydrogen.

There is a catch in the rush to new sectors. Most roles in solar and wind power promise only a fraction of the salaries in the minerals industry. Mining is in the blood in Australia, fostering almost every economic boom since the gold rushes of the 19th century.

“As a young fellow it made sense to go straight to the mines, trying to chase money,” said Dan Carey, who spent 12 years working in the remote iron ore hub of Port Hedland as well as the oil and gas town of Karratha in Western Australia.

In January, in search of a better lifestyle, he became a service technician at a wind farm in Warradarge, a three-hour drive north of Perth. Now “it’s about enjoying the work,” Carey said. “In the mining world, everyone does sort of live for the money.”

For example, the starting salary for an operator at AGL Energy Ltd.’s Loy Yang A coal power station in Victoria is about A$164,500 ($122,000) while a technician for wind turbine builder Suzlon would earn between A$100,000 and A$120,000, according to recent Fair Work Commission enterprise agreements.

In mining there are also a raft of perks, that could include 6 weeks paid leave, subsidized housing and utilities, free vacation air tickets and big bonuses. “It’s definitely going to be hard to retain people that have come from that world,” Carey said.

Also, while mining and coal power have provided work for generations of Australians, many new jobs in renewables are temporary.

“The challenge is that there are hundreds of jobs in construction and only a handful of jobs in operations and maintenance,” said Anita Talberg, director of workplace development at the Clean Energy Council, an industry group. And some of the highest-skilled jobs in fossil fuels have no direct equivalent in renewables, she said.

Yet the sheer size of the energy transition will mean construction of large new solar and wind farms will continue for decades, steadily increasing the number of ongoing positions as the new plants come online.

Fossil fuel veterans are well positioned to prosper, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency. Staff on gas platforms typically have expertise suitable for offshore wind, while coal workers have been recruited into solar and oil reservoir engineers can use their knowhow for geothermal power.

Australia’s first offshore wind farm, the Star of the South, is scheduled to open in 2028 in the Bass Strait, off the country’s southern coast. At about the same time, Hong Kong-based CLP Holdings Ltd. will close the aging Yallourn coal-fired plant nearby after more than 100 years of operation.

The wind project is aiming to capitalize on the pool of potential workers, and has sought talks about retraining opportunities. “You’ve got the workers with the skill sets,” said Erin Coldham, Star of the South’s chief development officer.

(By Georgina McKay, with assistance from Matthew Burgess)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments