As China reopens, Africa’s woes threaten to starve its factories

On a typical workday, hundreds of thousands of men clad in overalls and carrying safety equipment and headlamps assemble at South Africa’s mine shafts. They crowd into cramped elevators to be lowered miles underground, where they hack at seams of gold or platinum and haul ore in intense heat and humidity. After hours of backbreaking labor, they return to the surface to shower in communal areas, and many share meals and bed down in crowded hostels.

These aren’t typical days.

South Africa on March 26 imposed a three-week lockdown to fight the coronavirus, confining millions in their homes and shuttering most businesses—including the mines that are the first link in a global supply chain that passes through smartphone factories in China and auto plants in Detroit, Turin, or Tokyo, and ends in stores and showrooms around the world.

Even as Asia slowly reopens after its lockdown, factories there risk running short on supplies as the virus spreads to countries that produce vital raw materials. And nowhere is the problem a bigger issue than in Africa, which provides the metals and minerals needed for just about every industrial product, and where countries heavily reliant on trade with China have been suffering from a collapse in commodity prices.

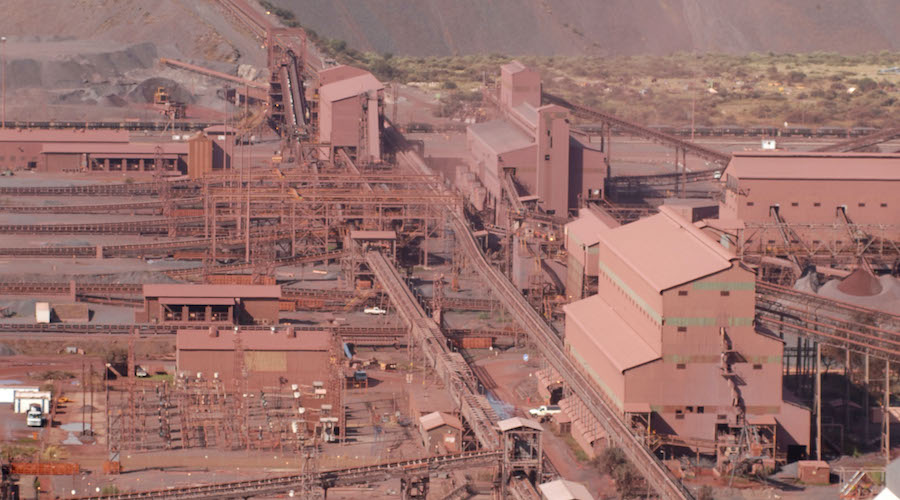

The African mines that produce raw materials for factories across the globe are bracing for the arrival of the virus

While the number of confirmed coronavirus cases across Africa remains low compared to other parts of the world—some 7,000 cases on a continent of 1.3 billion people—social distancing is a luxury the region can scarcely afford. Most governments lack the resources to enforce effective containment measures, and health systems risk buckling if the disease reaches Africa’s crowded shantytowns and slums.

“For Africa, it will be much harder than you imagine,” said Auret van Heerden, chief executive officer of Equiception, a supply-chain consultancy in Geneva. “They’ve survived Ebola, they cope with malaria and tuberculosis, but I don’t think they’ve had anything quite this infectious.”

The African mines that produce raw materials for factories across the globe are bracing for the arrival of the virus. In South Africa, Kumba Iron Ore Ltd., the continent’s largest iron-ore producer, and Anglo American Platinum Ltd. and Sibanye Stillwater Ltd., the world’s top platinum vendors, have curtailed most of their output. Chrome and manganese mines, which supply ingredients for steel, have been largely shuttered.

In Luabala, a province of Democratic Republic of Congo that is a major provider of copper and cobalt used in rechargeable batteries, mines remain open but the workforce has been limited to essential personnel to minimize the risk of contagion. Tenke Fungurume, a mine owned by China Molybdenum Co., has been put into isolation, with about 2,000 people ordered to stay on-site and avoid “contact with the outside world,” according to a memo circulated to staff.

Even facilities that keep producing risk interruptions in getting their goods to market. In the best of times, Africa’s transport networks are fragmented and inefficient, and its ports and customs services are notoriously slow. Today, most African countries have closed their borders, and several have limited internal travel or imposed lockdowns. While cargo is usually exempted from the restrictions, increased security controls, sanitation measures, and reduced staff at ports and railways threaten severe delays.

Most copper and cobalt from Congo’s mines, for instance, moves via truck through Zambia and then to ports in South Africa and Tanzania. While cargo carriers can still cross into Zambia, new sanitation measures have led to 25-mile backups at the border.

Even facilities that keep producing risk interruptions in getting their goods to market

In Kenya, a dusk-to-dawn curfew has resulted in a pileup of goods at ports, driving up freight costs by almost a third, according to Dennis Ombok, chief executive of the Kenya Transporters Association, which represents truck-fleet owners. Even though essential goods are officially exempted, drivers are being harassed by police, Ombok said.

“It’s taking up to three days to clear at the border between Kenya and Uganda,” he said. “The police need to tone down how they’re handling transporters. We’re carrying food and raw materials. These are essential.”

In South Africa, the port of Durban, the busiest in sub-Saharan Africa and serving landlocked Zambia and Zimbabwe, limited operations to essential cargo, and police stopped all trucks carrying other goods for several days. On Thursday, the order was reversed to help ease massive congestion at the port. Amid the confusion, First Quantum Minerals Ltd., which accounts for more than half of Zambia’s copper production, says it has started making alternative shipping plans.

At the main crossing between Zambia and Congo, more than 1,000 trucks carrying food, equipment, and supplies for mines had to queue last week after a partial lockdown came into effect. For now, Zambia has managed to convince the Mozambican government to allow trucks carrying fuel from the port of Beira to exit Mozambique, after they were held at the border.

“With a crisis of this magnitude,” Zambian President Edgar Lungu warned last week, “we shall find ourselves under forced lockdown if all our neighbors shut their borders.”

And global trade moves in many directions these days, so mines are facing potential shortages of crucial imports needed to keep operating as suppliers worldwide curtail production; sulfuric acid, for instance, is critical in copper processing. Both Zambia and Namibia, which ships copper and uranium to China, have raised the alarm over looming shortages of key chemicals for their mines.

“Most if not all our mining companies get inputs from China,” said Veston Malango, head of Namibia’s Chamber of Mines. “And we have not been able to do that.”

(By Pauline Bax, Matthew Hill and William Clowes, with assistance from Kaula Nhongo, Felix Njini, David Herbling, Taonga Clifford Mitimingi and Stanley James)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments