As banks shun coal, Vietnam emerges an unlikely solar champion

Nguyen Tuan was watching the sun shine down on his four-hectare cantaloupe farm in southern Vietnam when he realized it could do more than help his crops grow.

The 46-year-old installed 40 solar panels on greenhouses at his farm 55 miles outside of Ho Chi Minh City. Thanks to generous subsidies from the national utility, he not only cut his power bill but now earns about two million dong ($87) a month selling excess electricity to the nation’s grid.

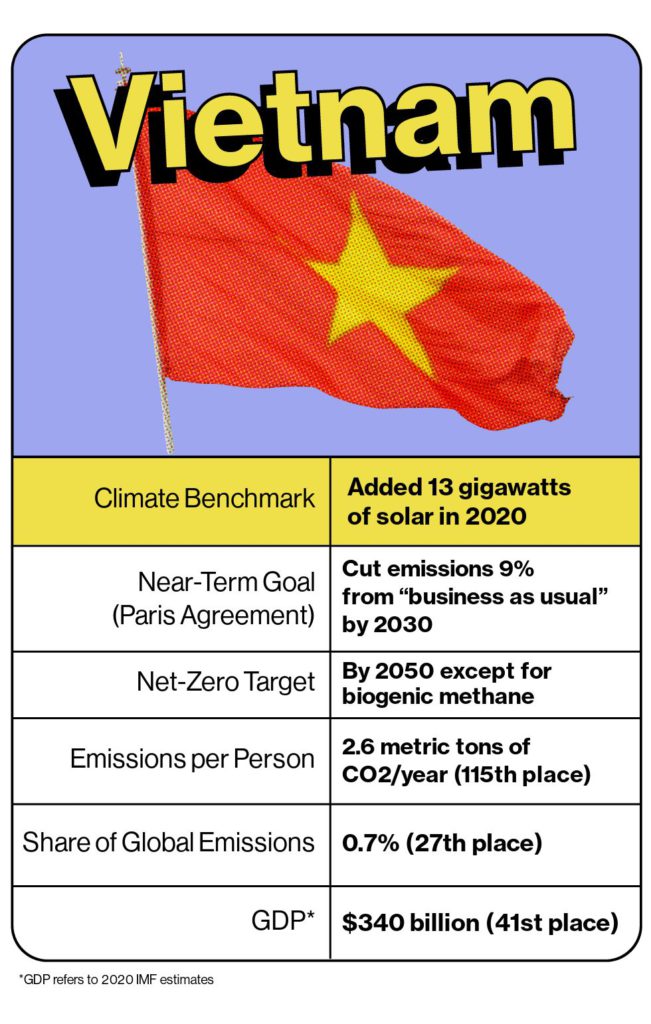

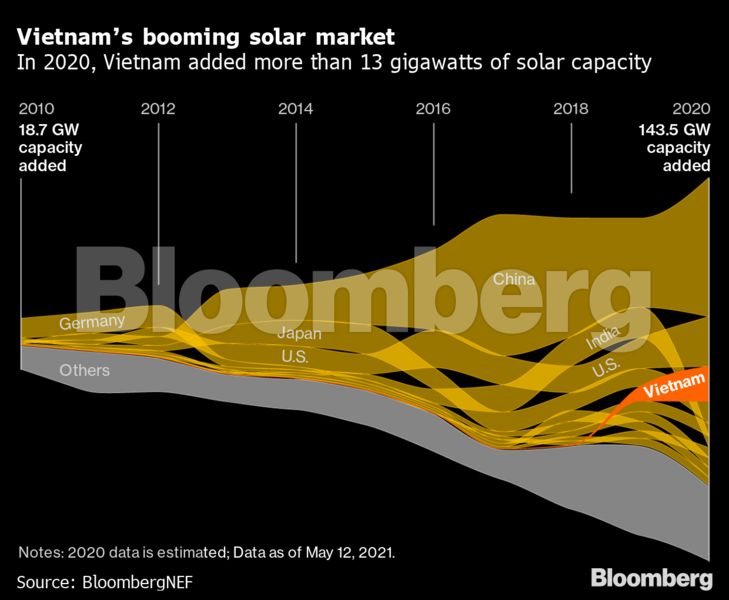

Tuan’s farm is just one tiny part of the extraordinary 100-fold increase in solar power that’s taken place in Vietnam over the last two years. The Southeast Asian nation now ranks seventh in the world in terms of capacity, according to clean energy research group BloombergNEF, and in 2020 the only countries that installed more solar panels were the U.S. and China.

The solar surge didn’t come from a government push to cut carbon pollution. In fact, Vietnam isn’t among the more than 100 countries with a net-zero target in the decades ahead. Instead, the embrace of solar is being driven by global forces. Foreign banks are limiting funding to fossil fuels projects, meaning Vietnamese utilities have struggled to get loans for new coal plants. At the same time, the plunging price of solar panels, many of which are assembled domestically, has created a cheap and convenient alternative.

“I have never seen a country explode like this in solar,” said Logan Knox, chief executive of Vietnam operations of UPC Renewables, which builds and operates wind and solar farms across Asia. “It’s almost unbelievable.”

That same shift to clean energy needs to happen in more developing countries if emissions worldwide are to be zeroed out by mid-century—a timeline needed to avoid catastrophic global warming. Vietnam is an encouraging sign that global efforts to discourage the use of fossil fuels and boost the accessibility of clean alternatives are bearing fruit. “What Vietnam’s solar boom shows is how much capacity you can build in a short period of time,” said Caroline Chua, a BNEF analyst.

In fact, Vietnam may have been too successful. Incentives to spur adoption are being paused or pared back to rein in the runaway buildout of new projects. While that action will cut the volume of installations in 2021, the rate will still be vastly higher than most recent years, BNEF data shows.

The government turned to the solar industry a few years ago as a growing number of power shortages threatened to sap its economic momentum. Years of rapid growth meant surging electricity demand from factories built by multinational giants including Samsung Electronics Co. and suppliers for Apple Inc.

A plan to meet that with an ambitious fleet of coal power plants has fallen behind schedule, due in large part to push-back from local leaders concerned about air quality and financing difficulties as global banks stopped lending for the dirtiest energy source.

The government was in favor of coal for a long time, but they’ve realized it’s not reliable anymore,” said Thu Vu, a Hanoi-based analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis. “At the same time, Vietnam’s economy continued to grow very fast, so they had to explore other options, so they pivoted to renewables.”

Even without an explicit end-date for emissions, more developing countries could be pressed into green progress by market forces. Bangladesh is abandoning all of its planned coal power plants but five that are currently operating or under construction. The Philippines last year declared a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants. Vietnam is already being seen as a template for other countries looking to add power generating capacity with coal sidelined.

Though there’s been strong solar adoption, without a government goal Vietnam is still rated badly on climate action by researchers. The country’s measures are labeled “critically insufficient” by nonprofit Climate Action Tracker. The country aims to lower emissions a paltry 9% from “business as usual” by 2030 and has a multi-billion dollar pipeline of liquefied natural gas projects that’ll keep fossil fuels in its energy mix.

Still, Vietnam produces just 0.7% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions and accounts for even less on a per capita basis. And while countries such as the U.S. and France had decades to enjoy the fruits of polluting before cutting emissions, Vietnam has only recently started industrializing—in large part because of conflicts driven by countries such as the U.S. and France.

Plunging so quickly into renewables has also brought new problems. The combination of intermittent solar power and Vietnam’s creaky grid means some areas have too much power while other regions face possible blackouts this summer and years into the future, said Le Viet Phu, an expert in environmental economics at Fulbright University Vietnam in Ho Chi Minh City.

At times, the state-owned utility pays more for solar power that feeds into the grid than the price it sells it for. The utility has to offer the high rates because its contracts don’t meet international standards and require projects to agree to unpaid output cuts if deemed necessary to stabilize the grid, raising concerns about financial returns, said UPC’s Knox.

A long and steady price decline of solar panels has also abruptly reversed this year, as strong demand has tripled the price of key raw material polysilicon, creating another hurdle for more solar adoption.

Vietnam’s new Power Development Plan VIII, a draft of which was published in March, attempts to address the network issues. It budgets $32.9 billion for grid expansion through 2030, along with $94.5 billion for additional power generation. The plan is still awaiting final approval after the ruling Communist Party reshuffled the country’s leadership earlier this year.

For Tuan and his farm, called BB Garden, adding solar panels was not only profitable, but good marketing. He sells about 6 tons of melons a month, each affixed with a sticker depicting a sun shining down on hills and a greenhouse.

“I am able to show my clients that our farm is a clean farm that uses clean-planting technology and clean energy as well,” he said.

(By Nguyen Dieu Tu Uyen, Dan Murtaugh and John Boudreau, with assistance from Jin Wu)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments