Arctic warming: another obstacle to resource extraction

The four-day heat wave that just enveloped British Columbia is nothing compared to what’s happening in the Arctic.

It is no secret that the Canadian Arctic and its polar neighbors have a serious problem with global warming. In 2019 the federal government released a scientific report claiming that Canada is warming at a rate twice as fast as the rest of the world — and will continue to warm at more than double the global rate.

Canada’s annual average temperature has warmed an estimated 1.7 degrees C (3F) since 1948; in northern Canada, the temperature increase is approximately +2.3C.

According to the report, rapid warming is due to several factors, including loss of glaciers, snow, and sea ice, thereby increasing absorption of solar radiation, and causing larger surface warming than in other regions.

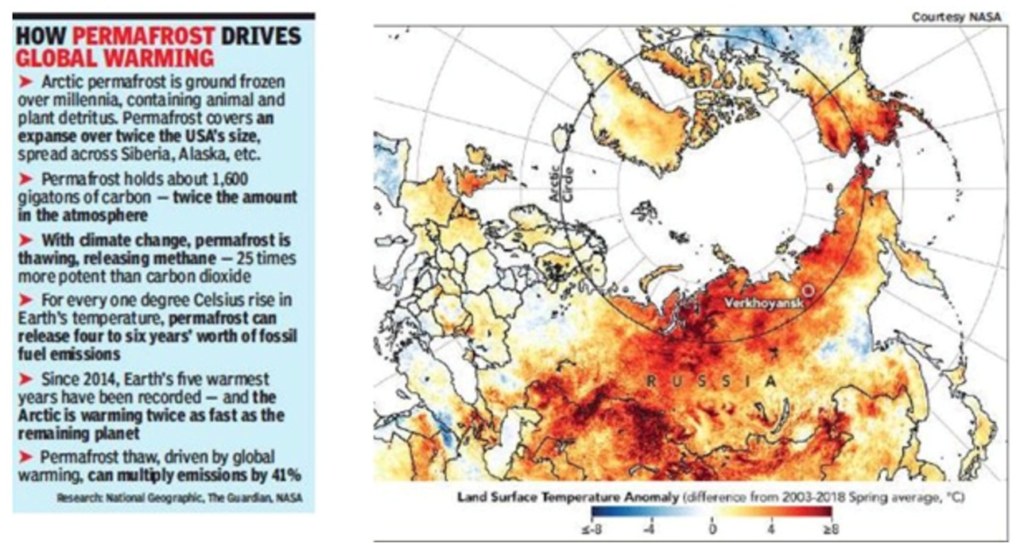

Along with calving glaciers, shrinking ice caps, and disappearing sea ice, evidence of Arctic warming can also be seen in the thawing of permafrost. Permafrost is land that is permanently frozen except for the top layer, which freezes in the winter and thaws in the summer; 70% of Russia sits on permafrost, which in some areas is over a kilometer deep. When it melts, permafrost exposes carbon dioxide and methane, a greenhouse gas that is about 30 times more powerful than CO2, in terms of its ability to trap heat.

It is estimated that this phenomenon could release between 300 million and 600 million tons of net carbon per year into the atmosphere.

Another negative impact of thawing permafrost, is subsidence. This is what happens when the surface layer gets deeper, and structures (like houses and industrial buildings) on or embedded in it start to fail as the ground beneath them expands and contracts.

Climatologists predict that an estimated 2.5 million square miles of permafrost, or 40% of the world’s total, could disappear by the end of this century, significantly accelerating global temperature rise.

Of course, the most obvious canary in the coal mine, regarding Arctic warming, is rising surface air temperatures; this is nothing new, in fact it’s becoming an annual event.

The Weather Network reports that Northern Canada is about to break heat records heading into the July 1 long weekend. Throughout June, temperatures across much of the region have been above-normal, with Inuvik, Northwest Territories on track to shatter its hottest temperature by Canada Day. The community’s all-time high of 32.8 degrees C, was reached twice, on June 7, 1999, and on July 20, 2001. As the mercury rises, Hudson’s Bay ice is melting at an astonishing rate.

Meanwhile in Yellowknife, NWT, the average high so far this month is 22.2C, well above the city’s typical average high of 18.7C. A ridge of high pressure that has been building over Northern Canada, saw the territorial capital experience two streaks of +20C weather, with the first streak lasting almost two weeks.

In June of 2021, “an intense and expansive heat wave,” Axios reported at the time, “has gripped parts of Siberia, northwestern Russia and Scandinavia, inducing a record plunge in sea ice cover in the Laptev Sea, which is part of the Arctic Ocean.”

In parts of Siberia, temperatures rose about 7C above average, Helsinki, Finland set the month’s highest minimum temperature of 22.5C during the night of June 21-22, and record heat baked Belarus and Latvia.

Concurrently, the US Pacific Northwest, and Canada’s Alberta and British Columbia, were trapped under a dangerous “heat dome” that killed over 600 people in BC. The Washington Post took the opportunity to investigate the phenomenon, and found that “Climate models project heat waves will regularly break records and induce more heat stress before the end of the century.”

Extreme heat events in the Northern Hemisphere have become more frequent over the past two decades. The World Health Organization reports over 160,000 heat-related deaths occurred globally between 1998 and 2017. Among the deadly events that stand out, according to WaPo, are the European heat wave of 2017, the Russian heat spell of 2010, Australia’s “angriest summer” of 2018-19, the Siberian heat anomaly in 2020, and last year’s Pacific Northwest heat dome.

Carbon Brief reported that prolonged heat in Siberia from January to June, 2020, which broke temperature records and caused massive wildfires, was made 600 times more likely by climate change.

In Verkhoyansk, the mercury rose to 38C — setting a record for the hottest temperature ever recorded above the Arctic Circle.

The Russian town was previously best known for sharing the Northern Hemisphere’s cold-temperature record — 90 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, set in 1892.

2019 saw one of Nunavut’s coldest locations, Alert on Ellesmere Island, warm up to a record-setting 21C, during July when the average summer temperature hovers just above 3C. In Iqaluit, the Canadian territory’s capital, heat records were broken four times from June to mid-July. The city also saw an abnormally warm and dry spring, with average temperatures in March, April and May bumping up two degrees higher, from -13C to -11C, and just 52mm of rain falling, compared to the 75mm the city usually gets over the spring months.

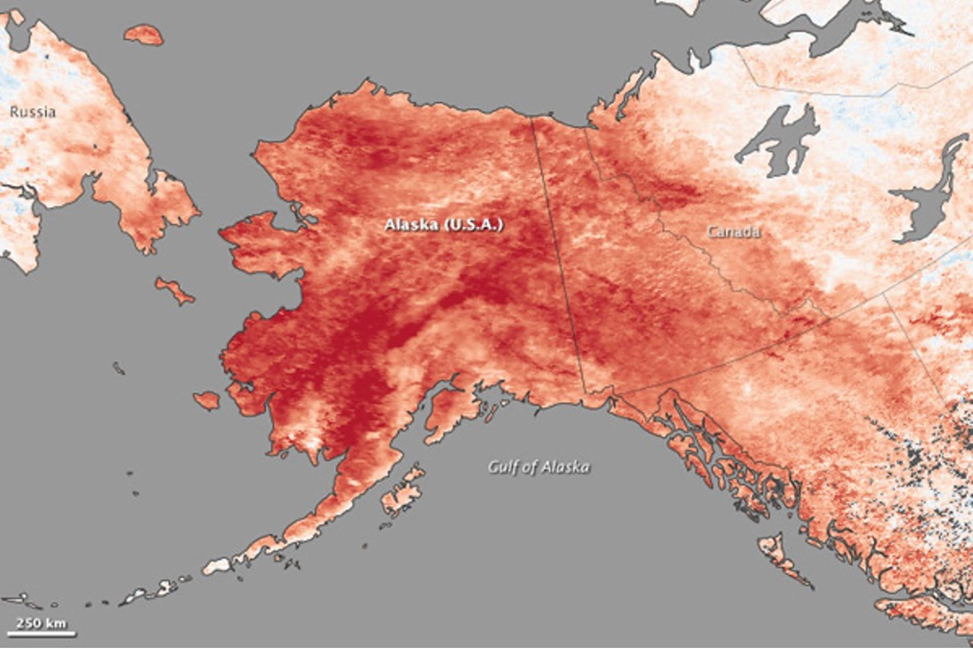

In 2014, it was Alaska’s turn to feel the heat. During the second half of January, the state experienced one of its hottest periods on record, with temperatures running 22C above average. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says climate change is the reason for Alaska being 1.9C warmer, on average, over the last 50 years, and for winter temps rising by 3.5C over the past half-century.

Researchers quoted in the Washington Post story found week-long record-breaking heat events were up to seven times more likely to occur from 2021 to 2050, and from 2051 to 2080, they are up to 21 more times likely and could happen every six to 37 years somewhere in the northern midlatitudes.

Arctic warming and mines

A warming planet not only affects human and animal populations, and their cities and habitats, but minerals extraction and processing.

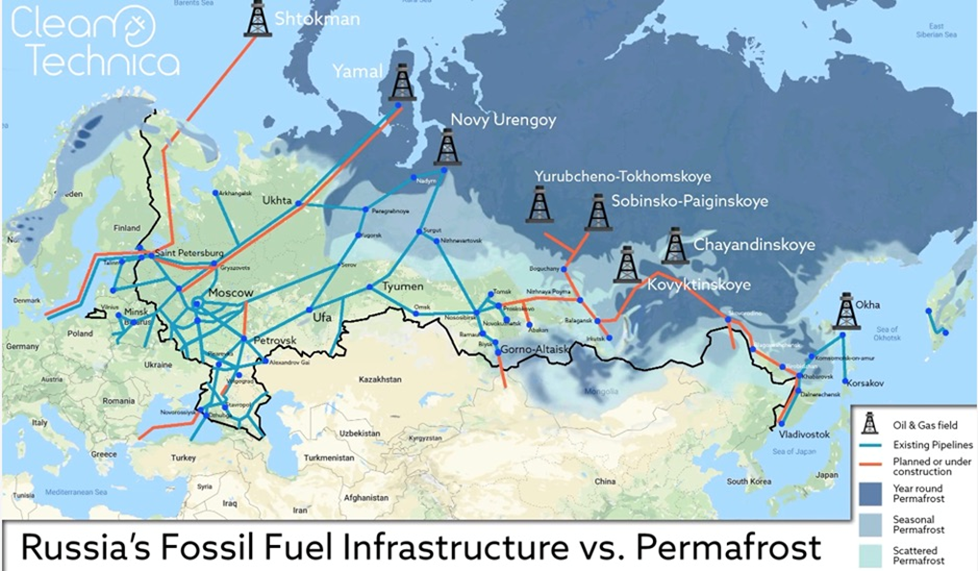

Two-thirds of Russia is encased in permafrost, but warmer temperatures are thawing it. A large share of Russia’s oil, gas and metals are produced in cities that sit on permafrost. Thousands of kilometers of roads, rails and pipelines could sink into the mud, and hundreds of buildings and processing plants will fall over if the ground thaws. Russia has 24 regions that are permanently frozen and while only nine of those contain extensive infrastructure and cities, they are key to Russia’s economy, producing raw materials that account for nearly half of Russia’s GDP. (‘Russia’s permafrost is melting’)

According to climate scientists, Russia especially its Siberian and Arctic regions is among the countries most exposed to climate change.

Hot spells have caused devastating forest fires and floods.

Last year, Norilsk Nickel had to partly suspend operations at its Oktyabrsky and Taimyrsky mines after noticing subterranean water flowing into one of them at a depth of 350 meters. Thawing permafrost was the likely culprit.

The Russian nickel and platinum group element miner reportedly had to install barriers and pour 30,000 tonnes of concrete into the underground mines in Siberia to stop the water flow.

According to Politico, the ground’s ability to support buildings across the country’s frozen north will degrade by up to a third by 2050, creating an infrastructure disaster that could cost $132 billion.

A paper published in ‘Nature Reviews Earth and Environment’ warns that, should the top three meters of permafrost thaw, it could result in the release of 624 million tonnes of carbon a year by 2100.

The study’s lead author, Jan Hjort from the University of Oulu in Finland, concludes that of 120,000 buildings, 40,000 km of roads and 9,500 km of pipelines currently built on permafrost, up to half are expected to be at high risk by 2060. The bill for maintenance could exceed $35 billion a year, he estimates.

So far, Russia has done little to protect its northern infrastructure, and with climate change only getting worse, the future looks bleak.

According to a 20-year study (1980-2000) quoted by The Economist, most of the damage to structures in parts of Russia covered by permafrost was due to poor maintenance: “If local authorities cannot even get the basics right, then large sections of the Russian Arctic may end up being abandoned altogether.”

Think about what that could mean for mining and oil & gas extraction. Most of Russia’s oil and gas network is built on permafrost, and almost all of its oil & gas fields are under permafrost, as the map below by Clean Technica shows.

The publication notes that the permafrost is rapidly thawing and could lead to a total collapse of Russia’s oil network.

Of course, Russia isn’t the only country with mines, oil and gas fields at risk from permafrost melting. Large Arctic operations include the Red Dog zinc mine in Alaska, the Diavik diamond mine in the Northwest Territories, and the Kiruna underground iron ore mine in Sweden.

Flooding isn’t the only concern; there could also be problems with lack of water. Hydrological changes this century could dry up one-third of the 45,000 lakes in Canada’s Mackenzie River Delta, one of the largest deltas in the world.

These changes to the local geography are exposing wildlife and human populations to wastes from current and former oil and gas and mining operations.

Scientists are finding that hundreds of sumps, excavated by the oil and gas industry in the 1970s and ‘80s, are thawing. Toxic petroleum waste that was supposed to be contained forever in 200 frozen pits is migrating into freshwater systems.

In the Siberian city of Norilsk, a fuel tank collapse in 2020 spilled 21,000 tons of diesel fuel into the Ambarnaya River, polluting an 180,000-square-meter area. The leak was blamed on abnormally warm weather and thawing permafrost, which weakened the tank’s structural integrity.

Acid mine drainage, or AMD, is what occurs when air and water react with mine tailings. The process generates sulfuric acid, which can leach heavy metals into nearby soils and waterways.

For decades, northern Canadian mine operators have stored waste rock and tailings — a pulverized rock slurry filled with chemicals like arsenic, lead, and mercury — in frozen dams reinforced by permafrost.

This method was cost-effective compared to building artificial tailings structures, and up to now there appeared to be little risk of the dam walls thawing. That, however, is changing.

With Canadian mining producing a million tons of waste rock and 950,000 tons of tailings per day, the prospect of widespread AMD in the far north due to permafrost enclosures failing is frightening to say the least.

It is not so much the big mines that concern experts on AMD, but the hundreds of small mines that have been abandoned and are not on anybody’s radar.

The Canadian government estimates it would cost over CAD$555 million to clean up abandoned mines in the north, but there are currently no requirements in mine closure planning to consider climate change.

Soil, groundwater, and creeks fouled by toxic waste from mining and oil and gas is not the only risk from thawing permafrost. There is also the delicate issue of water management.

In 2019 Teck Resources, which operates the Red Dog zinc mine in northwestern Alaska, said thawing permafrost linked to higher temperatures forced the company to spend nearly $20 million to manage its water storage and discharge.

Tens of millions more gallons were taken from the reservoir and frozen in an icefield, and Teck accelerated a plan to heighten the tailings impoundment.

As the Earth warms, mining infrastructure is increasingly vulnerable to changes in climate and weather, with the potential to affect buildings, pit-wall integrity, slope stability, tailings ponds and other water retention areas, and site hydrology.

Imagine having to work in a mine that no longer has solid permafrost on surface, but rather, has been transformed into a mud bog several hundred metes deep. Or in underground mining, trying to keep water from flooding into shafts, adits, ore passes and ramps.

Land-based transportation routes could face risks from melting permafrost including road embankment instability and accelerated erosion. Ice road networks will also be compromised, as a warming climate will make it more difficult to maintain sufficient ice thicknesses to support heavy traffic flow.

Other vulnerable areas include air strips, bridges, pipelines, operations that are highly dependent on water such as mineral processing, and mine closure plans. Decreases in annual precipitation may lead to drought conditions, making it difficult to maintain closure scenarios, such as sufficient water cover over tailings. Abandoned tailings ponds or waste rock dumps may not have been designed for climate change and will need to be monitored and retrofitted accordingly.

In sum, the potential for global warming to affect Arctic mining operations constitutes yet another threat to global mine supply, especially for minerals that are typically mined in the north. This includes nickel, palladium, diamonds, zinc, iron ore and gold.

Now consider that Russia supplies one sixth of the world’s commodities. According to JP Morgan, the country exports 45.1% of the world’s palladium production, 15.1% of its platinum, 9.2% of its gold, 5.3% of its nickel, 4.2% of its aluminum, 3.3% of its copper and 2.6% of its silver.

Should Arctic mines have to curtail production, or close indefinitely, due to the numerous and relentless effects of climate change, the missing production will be reflected in higher metal prices. In fact it’s reasonable to assumethat a lot of mines in Russia’s far north and in other Arctic regions such as Canada and Scandinavia, areas where the infrastructure is built on permafrost, and dependent on the ground staying frozen, will no longer be around. The mines and the means to supply them, i.e., roads, railways and airstrips, will either collapse into the mud or become too expensive to fix and maintain.

Conclusion

A warming climate brings a whole bunch of problems for Northern Hemisphere oil, gas and mineral producers like Russia.

The Kremlin under the direction of President Putin has carefully consolidated control of the country’s natural resources to become the world’s leading exporter of wheat, and a major oil and gas producer. In fact Russia is the planet’s sixth largest supplier of commodities.

Putin must have known that this status gave Mother Russia tremendous clout over the EU, which gets 40% of its natural gas from Russia. He would have also known that invading Ukraine would send oil, gas and wheat prices sky-high, enriching the country’s foreign cash reserves. Every barrel of oil and cubic foot of natural gas Russia sells to Europe, is adding to Putin’s war chest and prolonging the war.

The threat to Russia from NATO’s eastward expansion is cited as the reason for the war in Ukraine. But what if there was another reason for Putin’s aggression, that being a desperate attempt to cling to an oil & gas economy that Russia both depends on and is losing rapidly to due to resource depletion and the global shift from fossil fuels to electrification/ decarbonization? In other words, the war is less about politics, strategy, culture, or prestige, than the preservation of its oil-based economy, through military might.

Invading Ukraine was also a way for Russia to gain territory to the south, with access to ice-free ports on the Black Sea, and Ukraine’s vast grain fields, during a time when Russia is increasingly on the front lines of climate change.

Russia is among the countries most likely to be impacted by rising temperatures. Much of its oil and gas pipeline infrastructure is sitting on permafrost and nearly all of its oil & gas fields are under permafrost.

Most of the country’s nickel mines are in the Arctic. The ground is thawing, threatening to topple buildings, cave in open pits, flood underground tunnels, break pipelines, and damage roads, bridges and railways.

Repairing it is going to be very expensive. If oil and gas continue to be usurped by renewable energies and electric vehicles, the transition will diminish Russia’s ability to pay. So far the country’s leadership hasn’t shown itself up to the task of rebuilding/ relocating its infrastructure to safer ground.

Arctic warming is yet another obstacle to supplying the world with the metals it needs for the future economy, and further bolsters the investment case for commodities.

Most natural resource modeling has greatly overstated the amount of fossil fuels and minerals the petroleum and mining industries will be able to extract. Forecasters assume that as long as we have the technological capability, and resources are still in the ground, extraction will follow.

In fact this model greatly overstates the quantity of future resources that can actually be mined. For several minerals, including copper, grades are declining, meaning more ore has to be mined for the deposit to be economic. More complicated mineralogy often means more complicated, and more expensive, metallurgy.

The demand for metals is exceeding supply and the gap will get wider every year, without new deposits being discovered and developed.

Between China, the United States, Europe and Japan, we are talking about $5 trillion in infrastructure commitments over the next few years. Among the materials likely to be highly demanded for these major projects, are steel, rebar, aluminum, cement, sand and gravel. There will also be large amounts of copper required for wiring and plumbing, nickel-containing stainless steel reinforcement on bridges, zinc coatings used as corrosion protection for steel bridges, etcetera etcetera, the list of metals goes on.

For China’s Belt and Road Initiative alone, the International Copper Association estimates the demand for copper in over 60 Eurasian countries, could hit 6.5 million tonnes by 2027, a 22% increase from 2017 levels.

Then there’s the electrification and decarbonization imperative. Battery/ energy metals demand is moving at such a break-neck speed, supply will be extremely challenged to keep up. Without a major push by producers and junior miners to find and develop new mineral deposits, glaring supply deficits are going to beset the industry for some time.

Population explosion and urbanization, particularly in Asia and Africa, are macro demand factors pressuring supply. Climate change and resource nationalism are also throwing up impediments to bringing promising mineral deposits into production or expanding existing ones.

For shrewd investors looking to diversify their portfolios with low-risk, high-return assets, commodities remain the place to be.

(By Richard Mills)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments