Ancient sites, sacred snake raise risks for Australian resources

Sacred sites, endangered sawfish and mythical rainbow serpents are the latest challenges confronting commodities powerhouse Australia as the nation’s top mining companies meet for their biggest annual conference.

Since the destruction last year by Rio Tinto Group of a 46,000-year-old Aboriginal rock shelter at Juukan Gorge, the industry has been scrambling to deal with a backlash over heritage protection and environmental issues. A national enquiry into the incident and new laws being drafted by the Western Australia government could have an impact on some A$18 billion ($13 billion) in projects planned by mining giants operating in the Pilbara, the nation’s iron-ore heartland, as well as other resources projects.

The industry, which gathers on Monday for the three-day Diggers and Dealers conference on the edge of a huge gold mine in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, is already facing the threat of increasing restrictions on emissions, as well as a political spat with China, its biggest buyer. Now, Aboriginal communities are fighting for a stronger role to protect their culture from resources extraction and agriculture.

“The new legislation will put Aboriginal people at the center of decision making,” the Western Australia government said in an emailed statement. “One of the primary objectives of the bill is to ensure that Aboriginal people have custodianship over their heritage.”

Australia ranks among the top producers of metals from gold to lithium and some investors are concerned that if the rules don’t provide traditional landowners with enough safeguards, it could increase the risk of another damaging incident

The proposed new law will seek to strike a balance between giving indigenous people a stronger voice, without impeding growth in a resources industry estimated to have delivered a record A$310 billion in export revenue in fiscal 2021. Australia ranks among the top producers of metals from gold to lithium and some investors are concerned that if the rules don’t provide traditional landowners with enough safeguards, it could increase the risk of another damaging incident.

“This is a once in a generation opportunity to get a piece of legislation and not just try and fix it at the edges,” said Mary Delahunty, head of impact at pension fund Hesta, which has about A$60 billion in assets. She said the WA government’s draft proposal does not appear to go far enough in giving indigenous groups a stronger voice.

Traditional landowners agree.

“The current draft won’t prevent another Juukan Gorge,” said Wayne Bergmann, interim chief executive officer of the Kimberley Land Council, which represents Aboriginal landowners in the far north of the state. Bergmann is concerned that, under the proposed legislation, the final decision on whether work can be carried out in an area of cultural significance will still be the responsibility of whichever minister is in power at the time, rather than an independent expert body.

“Fundamentally, the investment community needs to be worried because this places risk on projects,” Bergmann said. The government says it was still drafting the bill, and had already made several revisions based on feedback from stakeholders.

Rio, the world’s biggest iron-ore miner, said it is giving cultural heritage and environmental issues a higher priority in the wake of Juukan Gorge and has set up an indigenous advisory committee to improve its engagement with local communities. The London-based company said in April it had reviewed over 1,300 sites in the Pilbara for their potential impact on cultural heritage, with subsequent additional safeguards resulting in 54 million tons of dry ore being removed from its reserves.

The fallout from Juukan Gorge is affecting more than the mining industry. The new legislation will also affect agriculture.

One example is the plight of sawfish, which are under threat from the demands of cattle stations that extract water from the Fitzroy River, one of the last remaining nursery habitats of the critically endangered freshwater sawfish, which can grow up to 7 meters long.

The distinctive rays, with their chainsaw-like snouts, are seen in Aboriginal culture as protectors of the river. The global range of the species has declined by more than 60% since the turn of the century, according to a 2019 study by Murdoch University’s Harry Butler Institute.

The WA government has extended a consultation process on water management plans for the Fitzroy River to the end of August.

The task of lawmakers is complicated by the fact that the new rules need to protect not only historical sites and the environment, but also cultural beliefs.

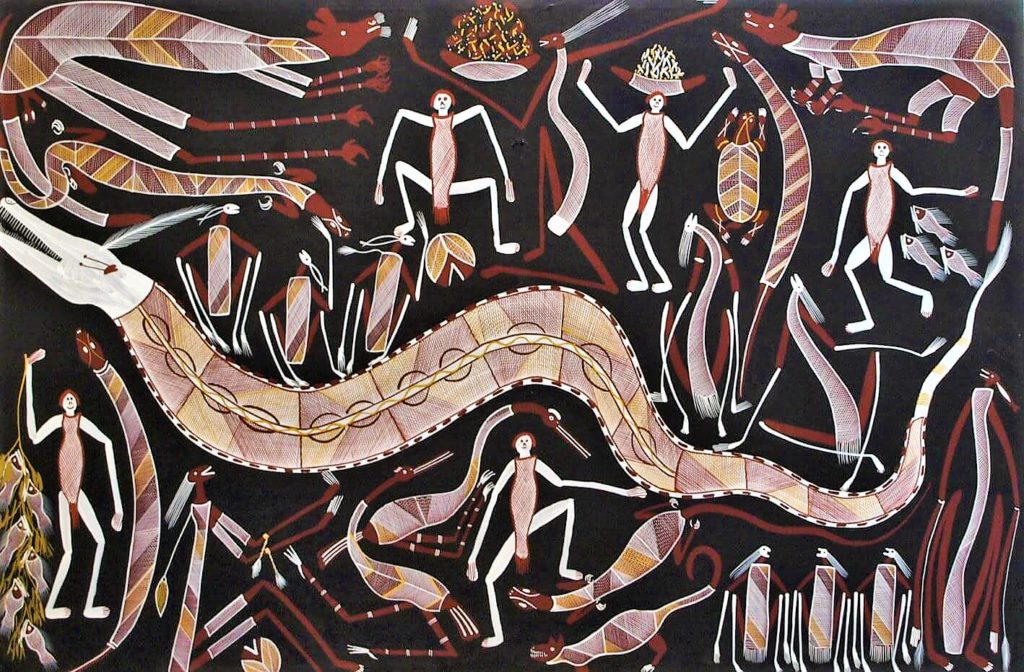

When iron-ore billionaire Andrew Forrest proposed building weirs on one of his cattle stations to hold water from the Ashburton River, the plan was rejected by the state government because of its potential impact on the rainbow serpent, which Aboriginal culture says resides in the river. Forrest’s legal team is appealing the decision, arguing that the weirs will have minimal impact on the river flow, and the serpent will still be able to move freely.

Night parrot

Forrest, who has a doctorate in marine ecology, has been a vocal supporter of the Aboriginal community — indigenous people make up around 12% of the Australian-based workforce at his Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. The company vowed to protect the endangered night parrot, which had been feared extinct prior to a 2005 sighting near the group’s Cloudbreak mine in the Pilbara.

Hesta’s Delahunty says landowner groups should have the right to veto projects, which would reassure investors that local community concerns were being taken seriously. “It’s important not just from a reconciliation point of view, but also to the financial outcomes of the company.”

The WA government said it won’t include a right of veto, which would be “a disincentive to agreement making.”

Meanwhile, resources companies are aware that their social license to operate is under closer scrutiny than ever. Rio’s former Chief Executive Officer Jean-Sebastien Jacques and other senior executives stepped down in the wake of the Juukan Gorge incident. Since Jacques’ departure, Rio’s shares have gained around 28% in London as iron-ore prices soared, but the FTSE All-Share Industrial Metals and Mining Index has more than doubled in the same time.

“Australia is watching,” Delahunty said. “The investment community is watching this process, because on our watch we will not have another of these incidents.”

(By James Thornhill, with assistance from Sanjit Das)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments