Analysts expect scorching base metals rally to cool

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

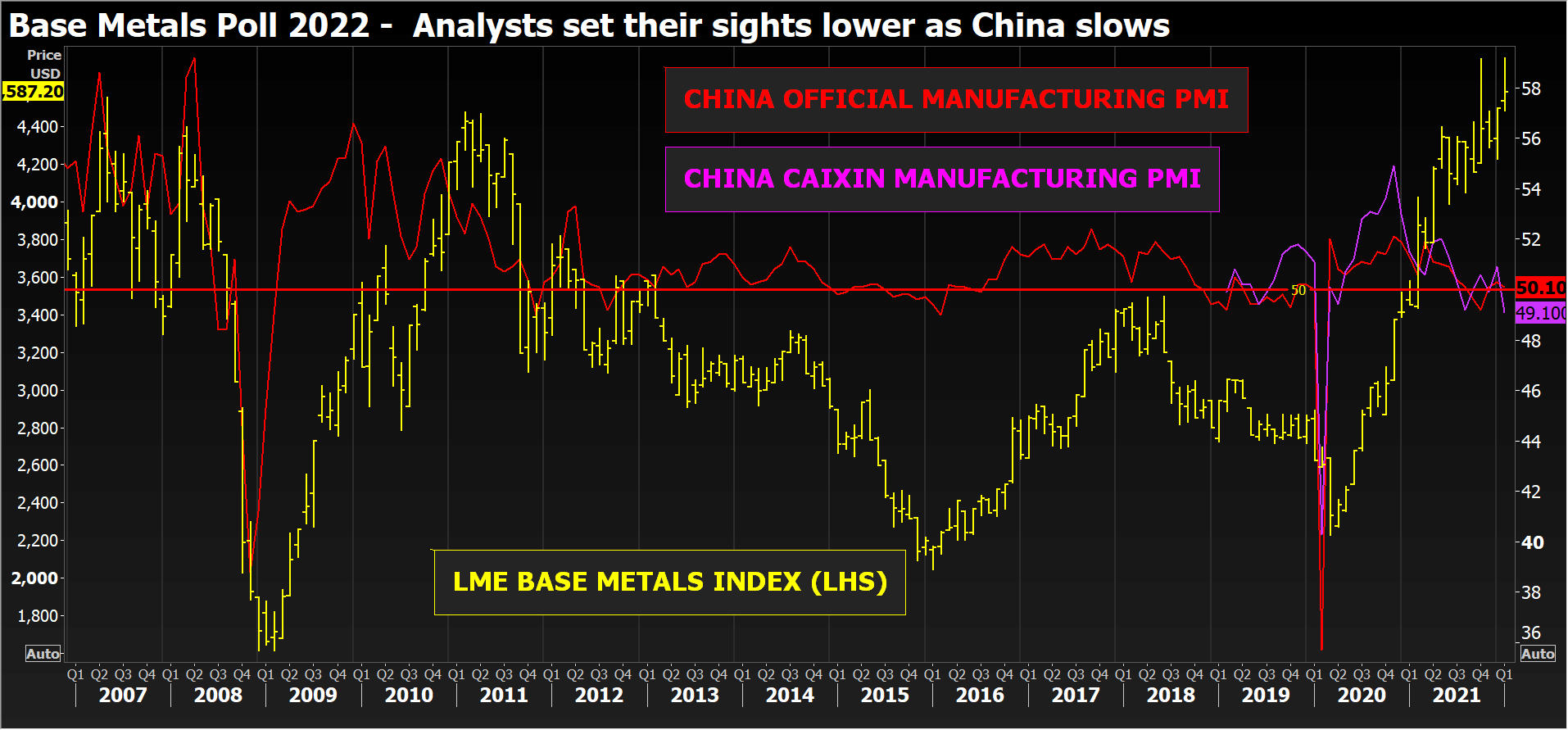

The London Metal Exchange (LME) index of base metals surged 38% higher last year as pandemic demand recovery met supply chain disruption.

Copper and tin soared to all-time record prices, while aluminum, nickel, zinc and lead each hit multi-year highs.

That, however, may be it for the super-charged rally, according to base metals analysts participating in Reuters’ January poll.

Median forecasts imply a retreat from current price levels over the course of 2022, the pull-back becoming more pronounced next year.

Market balances are expected to shift from supply deficit towards surplus in 2023 as production recovers and demand cools, particularly in China.

Given the LME Index has risen an eye-watering 93% since the first days of pandemic lockdown at the start of 2020, such caution is understandable.

It’s worth noting, though, that analysts were equally wary this time last year here, expecting prices to consolidate amid a growing supply surplus over the course of 2021.

Related Article: This chart says industrial metals prices have far to fall

A lot of stuff has happened in the intervening 12 months, particularly on the supply side, and even last year’s highest forecasts failed to match the bull reality.

That tells you just how wild the base metals markets have been – and not everyone thinks they are going to get any calmer.

Goldman Sachs is sticking to its super-cycle bull guns.

Rise and fall

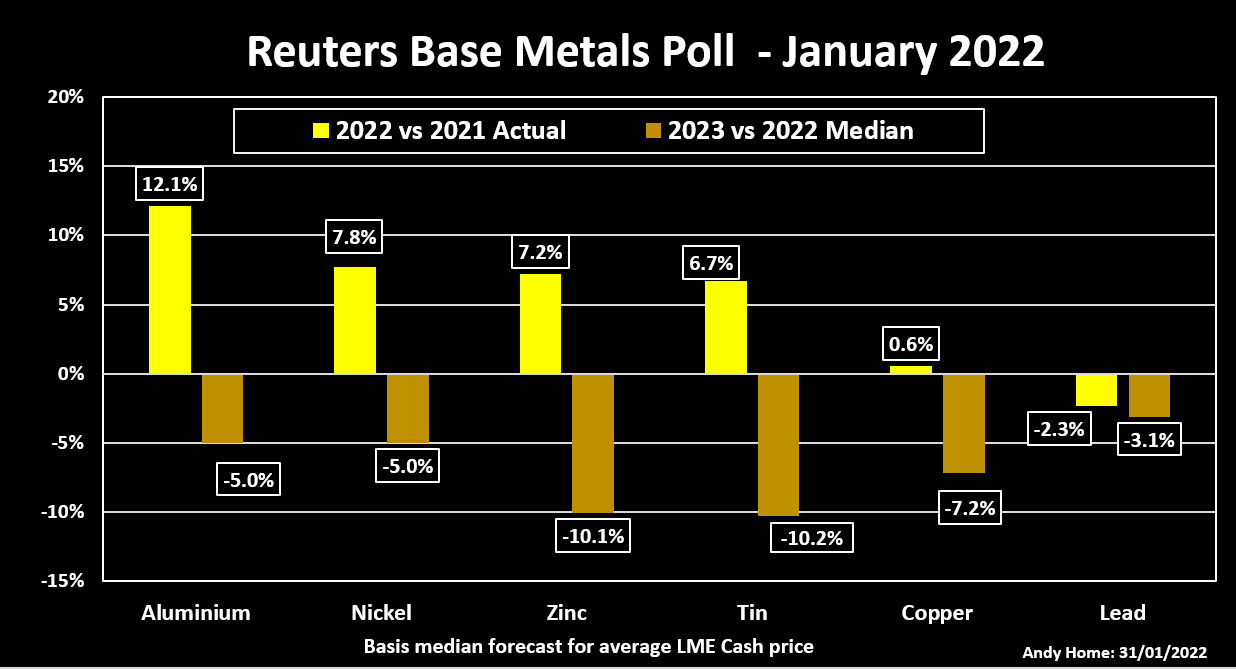

Average LME cash prices for all the base metals are expected to be higher this year relative to last, with the single exception of lead.

It’s no coincidence that lead is also expected to be the only market to register a supply-demand surplus in 2022.

Aluminum is forecast to be the relative out-performer with an average cash price of $2,780 per tonne, representing a 12% jump on last year.

However, remember that LME cash aluminum was trading below $2,000 per tonne this time last year, which serves to flatter the year-on-year comparison.

Perhaps more tellingly, the median forecast is significantly below today’s LME cash price, last trading at $3,070.

So too are the forecasts for all five other LME base metals. The inference is that analysts may be looking for prices to hold or even rise over the short term, but think they will soften over the year as a whole.

That retreat is expected to broaden out over the course of 2023, with median forecasts lower across the metallic board relative to this year.

Copper seems particularly out of favour.

This year’s median forecast of $9,370 per tonne is only 0.6% higher than last year’s cash average, and the price is expected to fall further to an average $8,700 next year.

Underlying that subdued outlook is an expectation that a supply deficit of 37,000 tonnes will turn into a surplus of 286,000 tonnes in 2023.

Indeed, only aluminum and tin are expected to remain in supply shortfall next year. Zinc is forecast to be balanced, and nickel and lead are both expected to record supply surpluses – for a second consecutive year, in the case of lead.

Fading demand growth

Looming large over any poll of base metal analysts is China, which has been the engine room of demand growth for most of this century.

Chinese factory activity shows signs of stalling, with both official and the Caixin purchasing managers indices slipping in January here, the latter dropping to a 23-month low.

The negative implications for metals consumption is the area of greatest concern for analysts, and explains why many have turned more conservative in their price outlook.

Capital Economics for example argues that, “with Chinese demand unlikely to bounce back meaningfully this year, we continue to expect sharp falls in industrial metals prices by year-end”. (“Weaker China sets stage for fall in commodity prices,” Jan. 31, 2022)

The research house is at the bear end of the poll spectrum, with the lowest forecasts for both aluminum and lead next year.

Chinese policymakers may open the stimulus taps to steady the economic boat, but the Evergrande saga is a warning that problems in the construction sector – a key driver of metals demand – may be as much structural as cyclical.

That’s one reason analysts are looking for a sharp 10% retracement in the average zinc price next year. Zinc is particularly exposed to construction in the form of galvanized sheeting.

Recovering supply?

Expectations of softer prices are also based on a calculation that this year’s supply disruptions will abate.

Energy crises, first in China and now in Europe, have hit power-hungry smelters, constraining production of metals such as aluminum and zinc.

Both power availability and pricing should improve for smelters as warmer weather comes.

But the winter crises in both China and Europe have laid bare structural problems facing high energy-use metals plants in a world that is trying to move away from fossil fuels.

China’s energy efficiency targets won’t go away, and neither will Europe’s high energy prices while the stand-off with Russia over Ukraine continues.

That injects considerable uncertainty into the supply picture, and prices remain hyper-sensitive to unexpected hits because visible inventory is still so low.

LME copper stocks came close to evaporating last October. The resulting market mayhem prompted the exchange to step in to restore order.

After a modest rebuild, headline inventory is falling again and more copper is being canceled every day. Available tonnage stands at 60,075 tonnes, the lowest since November.

Tin has been operating with depleted LME stocks for over a year, which is why the price is still punching out record highs on a regular basis.

The soldering metal is an example of scarcity price, and ongoing stocks depletion in markets such as copper and aluminum means they could go the same stratospheric way, according to Goldman Sachs.

The bank cements its super bull standing in this year’s poll with the highest forecasts for aluminum, copper and zinc both this year and next, and the highest for nickel in 2023.

Goldman’s super-cycle view of industrial metals makes it the contrarian stand-out in the current cautious consensus.

But as last year proved, the consensus doesn’t always turn out to be right.

(Editing by Jan Harvey)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments