An obscure Chinese mining law is hobbling global energy security

China’s current energy crisis can be traced back in part to a legal amendment targeting miners that garnered little notice when it went into effect in March.

Article 134 in China’s criminal law elevated penalties for a series of violations from fines to possible jail time in response to an increase in mining-related accidents. However, that law led to a newfound hesitancy among miners to boost production and intensified a supply deficit that could not come at a worse time for President Xi Jinping as the country faces a severe power crunch amid a surge in energy demand. The crisis also threatens to slow economic growth and snarl global supply chains.

The heightened punishments are a key reason that miners were hesitant to increase their output despite government calls to ameliorate the power crisis, according to five traders and analysts who spoke to Bloomberg this week on the condition of anonymity. The industry’s ability to flexibly respond to demand surges has been further stymied by increased safety inspections and an anti-corruption campaign in a major coal-producing region.

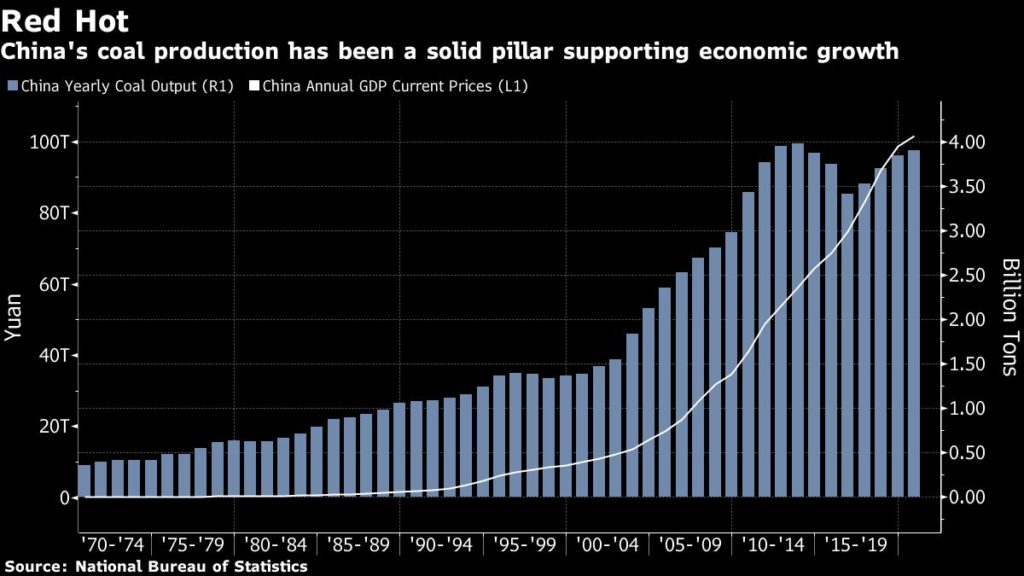

China’s current power crunch is affecting about 20 provinces and regions, representing over 66% of its GDP. Coal has long been central to China’s power generation, and broader economy — the country produced around 3.8 billion tons of coal every year in past decade, the same level as the rest of the world combined.

Prior to the enactment of the legal amendment, the miners were able to respond more nimbly. For example, when the industrial recovery from the pandemic caught miners by surprise last winter and led to coal shortages and power cuts during a December freeze, miners drove production to an all-time record that month amid orders to boost output. The surge in prices cooled by the end of February.

But that ramped up production came at a cost. Mining deaths reversed a years-long trend and rose. Officials later placed the blame on companies for allowing unsafe practices in their rush to benefit from higher prices. Article 134, aimed at reducing casualties, came following those tragedies.

Along with the stricter penalties came increased safety inspections ahead of the Communist Party 100th anniversary celebrations in July. The party has long been associated with coal miners, as a young Mao Zedong helped organize a historic strike among coal miners in the city of Anyuan in Jiangxi province, an effort that was immortalized in one of the most famous paintings of the iconic leader.

Further exacerbating the problems for coal miners is a corruption probe that begin in early 2020 in the autonomous region of Inner Mongolia, which was once the top producer of coal in China. Output there has fallen for two straight years since 2019, while a nationwide effort to reduce overcapacity in the past decade forced closures of many outdated and dirty coal mines.

The result: Coal production overall has stalled. Output was up 16% year-over-year at the end of the first quarter, but that has dropped to just 4.4% at the end of August. Meanwhile, thermal power demand is up 14%, leaving coal inventories shriveled and prices soaring to record levels.

Coal is now so expensive in China that most power plants are operating at a loss. Some are running at reduced levels or shutting for maintenance to avoid hemorrhaging more cash, contributing to the electricity shortages. A possible La Nina weather event this winter, which would bring colder-than-usual temperature, would further worsen the crisis.

(By Alfred Cang, with assistance from Dan Murtaugh)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments