America’s Suez

Amid bombastic statements that scared US consular officials and alienated allies, like calling North Korea’s Kim Jong-un “rocket man”, rejecting the Iran nuclear deal and declaring that the US embassy would be moved from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, former President Trump occasionally had flashes of brilliance.

One such instance was said to have occurred regarding Taiwan.

According to John Bolton’s memoir, Trump liked to point to the tip of a Sharpy and say, “This is Taiwan,” then motion to the desk in his Oval Office and say “This is China. Taiwan is like two feet from China, we are 8,000 miles away. If they invade there isn’t a f&%*ing thing we can do about it.”

The visual metaphor obviously glosses over the details of America’s complex relationship with the island nation perennially at odds with Beijing, but Trump’s point was well made.

Despite US assurances that it will come to Taiwan’s defense should it ever become necessary against Chinese aggression, the reality of the situation is that in a war against China involving Taiwan, the United States is unlikely to take up arms.

Steve Bannon famously stated that he sees such a war as inevitable within five to 10 years. Trump followed the advice of China hawks like Peter Navarro and began a trade war that scaled up to hundreds of billions in tariffs slapped on Chinese goods, actions which were duly countered by Beijing.

It’s not that big of a leap to go from a clash of economics to a serious conflagration that results in a shooting war. The US pulled out of the 1987 INF Treaty restricting intermediate-range nuclear missiles, so we already have an arms race between the US, Russia, and China. We correctly predicted rare earths could be used as pawns in the trade war.

We also have heightened tensions in the South China Sea, which China claims as its own and the US insists is an international waterway; over Taiwan, a chunk of the former Chinese empire that went independent, but that China considers part of its territory it will fight to defend; and over North Korea’s nuclear capabilities.

Defending South Korea is one of the US military’s most important mandates in the Pacific theater. For China, continued propping up of Kim Jong-un’s regime through strong trade linkages and aid (in 2018 Beijing said it will invest $88 million in the North’s infrastructure such as a new border bridge), serves to consolidate Chinese power in North Asia, and to prevent a major refugee crisis should the North and South unite as East and West Germany did in 1989.

At Ahead of the Herd, we’ve been talking about a potential war between China and the US for years. It’s not news to us.

In this article we take a deep dive into the US ability to project power thousands of miles from home, against not only its greatest economic and military adversary, but an existential threat to US hegemony in the Pacific region.

Thucydides Trap

The Thucydides Trap is a term invented by Graham Allison, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Allison has been saying since 2015 that war between a rising power, China, and an established power, the United States, is inevitable, based on historical examples. The argument is fleshed out in his book, ‘Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’sTrap?’

We all know the story of what happened to China in the 2000s. Its GDP raced along at double-digits for nearly a decade. The country became the largest commodities consumer in the world, the most important market driver of raw materials like copper, iron ore, coal, oil, and soybeans.

Today, anybody who knows anything about commodities keeps a close eye on China.

China’s open-ness to world trade meant that in 2001, it was let into the World Trade Organization. Member nations, particularly the United States, presumed that China would thus become more “Westernized” and respect the status quo. In fact, what has happened, is that China has taken over a lot of what the US used to control.

For example, at the beginning of the 21st century, the US was the dominant trading partner of every Asian nation; now that position belongs to China. According to Allison, this is like a red cape to a charging bull. Ruling powers do not like to be challenged.

It might be hard for Westerners to understand the Chinese perspective. We know the Chinese government wants to have better lives for its citizens, to become richer, to have better jobs, higher-educated kids, more brand-name stores, etc. Essentially, to become more like us. Isn’t that the goal of every developing nation? Well yes, and no.

In China’s case, it goes much further than that. Chinese leaders see their country as a lost empire that needs to be regained, respected, both loved and feared. They want China to assume its rightful place in the world; for them, this means the most powerful, envied, and emulated nation on Earth.

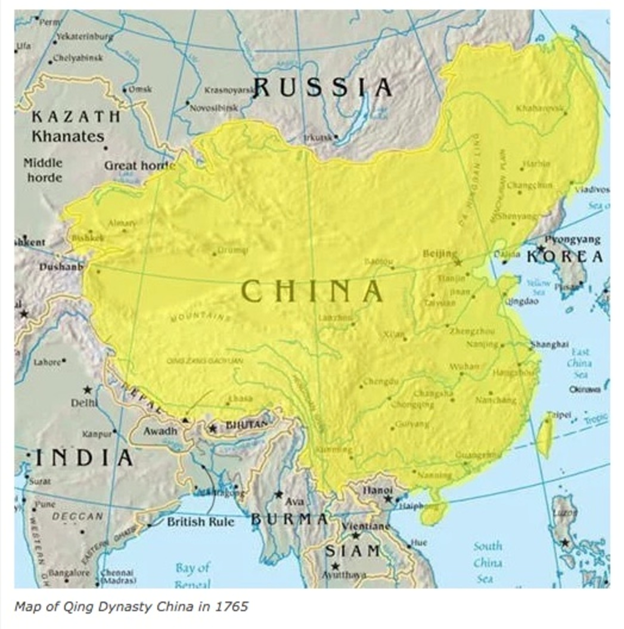

A knowledge of history is important here. Hundreds of year ago China was the undisputed ruler of North Asia. Chinese history is a series of dynasties. The last dynasty was the Qing, or Manchu; the Qing held power for 268 years, from 1644 to 1912. At the peak of its empire the Qing controlled 13 million square kilometers of territory including parts of modern-day Vietnam, Myanmar, Tibet, India, and North Korea. Among its major achievements were an expansion of foreign trade, the creation of vast encyclopedias (the Imperial Encyclopaedia written between 1700 and 1725 reportedly contained 10,000 volumes), a large body of literature, development of the Peking Opera, and advances in painting, porcelain and printing.

Allison believes nations act purely out of self-interest (in this respect he is in the camp of philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who wrote “life is nasty, brutish and short”) and that conflict is pretty much inevitable when a powerful up-and-comer nation is trying to usurp the incumbent country’s dominance.

This is what Allison refers to as the Thucydides Trap. Its namesake was a Greek historian who gave an account of the Peloponnesian Wars in the 5th century BC, between Sparta, the champion, and Athens, the challenger.

Thucydides concluded “it was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable”. Why couldn’t they just work out their differences? According to the theory it’s this unique situation – where a zero-sum mentality forms in the minds of the pursuer and the pursued, characterized by overconfidence of the rising power, and loss of confidence/ paranoia of the declining hegemon – that causes the powers to fall into the “trap” of war.

Could it happen to the US over Taiwan? At AOTH we believe, like Bannon and Navarro, that a clash, maybe even a war, between the two superpowers is inevitable. Whether America has the stomach to fight, is an entirely different question.

US vs China

China has bulked up its military and it now spends more on its armed forces than any other country in the world except the United States. And changes are occurring with China’s military institutions. In a feature article titled ‘The China Challenge: Marshall Xi’ Reuters writes that President Xi has refashioned the People’s Liberation Army, the PLA, into a force that is rapidly closing the gap on US firepower. In fact, the US could lose, if the two sides were to meet in combat:

In just over two decades, China has built a force of conventional missiles that rival or outperform those in the U.S. armory. China’s shipyards have spawned the world’s biggest navy, which now rules the waves in East Asia. Beijing can now launch nuclear-armed missiles from an operational fleet of ballistic missile submarines, giving it a powerful second-strike capability. And the PLA is fortifying posts across vast expanses of the South China Sea, while stepping up preparations to recover Taiwan, by force if necessary.

For the first time since Portuguese traders reached the Chinese coast five centuries ago, China has the military power to dominate the seas off its coast. Conflict between China and the United States in these waters would be destructive and bloody, particularly a clash over Taiwan, according to serving and retired senior American officers. And despite decades of unrivaled power since the end of the Cold War, there would be no guarantee America would prevail.

While there are still plenty in US military circles who doubt the strength of their competitor, China’s path to superpower status is more assured than many would like to believe. Consider the following excerpts from this recent article in Defense One, provocatively titled ‘Let’s Get Real about US Military ‘Dominance’:

- It is true that demographic and other challenges that China faces are likely to undermine its great power status—but only long after it has achieved such status and surpassed the United States.

- It’s time for more realistic futures analyses in the U.S. armed forces.

- According to several forecasts, China’s economy will soon be the largest in the world when measured at market exchange rates, or MER. (It already is in terms of purchasing power parity, a correction meant to account for levels of development.)

- China already leads the United States in the worldwide trade in goods. Last year, it became the top trading partner of the European Union, an area where U.S. trade dominated only a decade ago.

- Militarily, the U.S. continues to retain a distinct advantage. But for how long? If “economic development improves a state’s ability to produce high-quality military equipment and skillful military personnel,” as political scientist Michael Beckley observed, China’s abilities to produce a world-class military should be expected to continue to grow at an impressive rate.

- Indeed, a future world with China as the leading power should be the base-case assumption, one that will only likely be avoided by severe destabilization within the Chinese Communist Party.

Yet the US appears to be girding for a military challenge. Bloomberg reports that the Pentagon has been working to overhaul the “two-war” defense strategy that has been the playbook for the last couple of decades — in other words, preparing to fight one major war as opposed to two smaller conflicts simultaneously. The one-war strategy is rooted in the idea that defeating a great-power adversary like China or Russia would be more difficult than anything the US has done in decades and is a 180-degree shift from the DoD’s focus on counter terrorism that has dominated the thinking since 9/11.

The US is now building a force not around the demands of two regional conflicts with rogue states, but around the requirements of winning a high-intensity conflict with a single, top-tier competitor — a war with China over Taiwan, for instance, or a clash with Russia in the Baltic region.

There is plenty of serious thinking behind this shift. The new strategy is meant to signal unambiguously – to allies, competitors, and the Pentagon bureaucracy – that the US is now focusing squarely on great-power competition and the immense challenges it presents for a force that has been preoccupied with counterterrorism and counterinsurgency for nearly two decades. It recognizes that America’s military advantages vis-à-vis China and Russia have eroded gravely, and that the Defense Department will need new high-tech capabilities and creative operational concepts to defeat either country should war break out.

A 2019 op-ed in the highly respected ‘Foreign Policy’ magazine states that For now, U.S. forces appear poorly postured to meet these challenges. That’s because both Russia and China have developed formidable networks of missiles, radars, electronic warfare systems, and the like to degrade and potentially even block U.S. forces’ ability to operate in the Western Pacific and Eastern Europe to defend allies and partners in those regions. China, in particular, is developing increasingly impressive capabilities to project military farther afield, including through systems such as aircraft carriers, long-range aviation, and nuclear-powered submarines. Together, these forces have tilted the military balance over places such as Taiwan and the Baltic states from unquestioned U.S. dominance to something much more competitive.

The question is what to do about it. Left unchecked, China or Russia may seek to exploit these advantages to coerce or even conquer U.S. allies or Taiwan.

Meanwhile the two US adversaries are cozying up in various ways, such as holding joint military exercises. In 2020 Xi Jinping described Vladimir Putin as his best friend, and on a call between Beijing and Moscow reported by The Diplomat, Xi and the Russian president agreed to work “unswervingly” to develop an ever-closer partnership and that “strategic cooperation between China and Russia can effectively resist any attempt to suppress and divide the two countries.”

This opens up the possibility of the US having to take on Russia and China at the same time. Could the US win against a united Sino-Russian front?

A recent DefenseNews article posits that the US would be better off concentrating on China (and surprisingly, emulating the PLA), especially given the muted power of Russia compared to when it was the Soviet Union:

First, the United States will increasingly focus on China as the pace setter for its own military modernization. China’s defense budget measured in purchasing power parity may soon approach that of the United States. China’s time and distance advantages, its focus on a naval and missile buildup, and its growing tactical nuclear capabilities have already created a major challenge for America’s forces in the Indo-Pacific theater. With future U.S. defense budgets likely to be flat, at best, America’s defense priorities may need to concentrate on China. The European theater may get less attention than when Russia presented the primary major power threat.

Spoiling for a fight

Back to the Taiwan conflict, there is an almost daily news flow about the deteriorating conditions in the Strait of Taiwan and the South China Sea.

In recent months, Taiwan has complained of an increase in Chinese military activity in the waters off the democratically run island. A carrier group led by China’s first aircraft carrier, the ‘Lianoning’, was reportedly carrying out drills in the waters near Taiwan this week.

“Similar exercises will be conducted on a regular basis in the future,” the Chinese navy said in a statement.

In December 2019, a Chinese warship sailed through the Taiwan strait shortly before Taiwanese elections, provoking an alarmed response by Taipei who called it “intimidation”.

The country’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, is currently overseeing a revamp of Taiwan’s military, including the dispatch of new equipment such as “carrier killer” stealth corvettes, according to a recent Reuters story.

The naval exercises are in addition to a new incursion by China’s air force into the island’s air defense identification zone. Taiwan’s Defence Ministry says 12 Chinese fighters entered the zone and were warned off by Taiwanese aircraft.

Another Reuters article, republished in the National Post, quotes Taiwan’s Foreign Minister, Joseph Wu, saying, “We are willing to defend ourselves without any questions and we will fight the war if we need to fight the war. And if we need to defend ourselves to the very last day, we will defend ourselves to the very last day.”

Details of Taiwan’s Quadrennial Defense Review, reported by Defense One, include calls to improve its “deep strike” missile arsenal. The nation already has a subsonic “Tomahawk-like” cruise missile with a maximum range of 600 km, and a supersonic anti-ship cruise missile with a 160-km range.

According to Defense One, China cannot ignore a missile threat, because these weapons will make coordinating its landing forces, directing long-range strikes, launching aircraft, and staging reinforcements far more difficult.

While China has said its military movements are aimed at protecting China’s sovereignty, the US is reportedly standing by Taiwan. Its long-time ally and arms supplier is apparently pushing Taipei to modernise its military so it can become a “porcupine”, hard for China to attack.

Near the Philippines, Chinese fishing boats have been sitting along a disputed reef in the South China Sea, in a tactic previously used by Beijing to test the resolve of the United States.

At one point in March, 220 vessels were anchored around Whitsun Reef, prompting protests from Vietnam and the Philippines which both have claims. Two weeks later about 40 fishing boats are still there. China’s Foreign Ministry says the boats are simply “taking shelter from the wind” but China has previously used large fleets of ostensibly civilian boats — in fact they are armed and officially called the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) — to press other countries’ vessels out of disputed waters.

Not long ago, China asserted its claims on the South China Sea by building and fortifying artificial islands in waters also claimed by Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia. Its strategy now is to reinforce those outposts by swarming the disputed waters with vessels, effectively defying the other countries to expel them.

Observers say the tactic is also seen to embarrass the United States. In 2012, the US lost face when it failed to strike a deal for mutual withdrawal at the Scarborough Shoal, an island in the South China Sea.

An American Suez

American loss of face over Taiwan in fact may happen a lot sooner than anyone is expecting. A recent article by historian/ author Niall Ferguson fleshes out the various reasons why China would be better off attacking Taiwan sooner than later. (by sooner he means within the next five or six years)

These include the fact that Taiwan’s capabilities are currently run-down; China has momentum in successfully changing Hong Kong’s status and tightening its grip on Xinjiang, amid minor and manageable international opposition; China must worry about the rise of India, the re-arming of Japan and a recalcitrant Southeast Asia; and finally, the fact that the Chinese Communist Party could face increasing fractures and lose some of its grip on power.

Ferguson also argues that China probably regards Biden as a weak US president and that “the Chinese may believe it is time for America’s comeuppance.”

He goes further in comparing a potential Chinese attack on Taiwan to what happened to Britain during the Suez Crisis. In 1956 Egyptian President Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, prompting an invasion of Egypt by Israel, the UK and France. For six months the canal was closed to shipping. After fighting started, political pressure from the US, the Soviet Union and the United Nations led to a withdrawal of the three invaders. The episode is remembered as a humiliation for the UK and France, and a victory for Egyptian President Nasser.

Ferguson writes:

Perhaps Taiwan will turn out to be to the American empire what Suez was to the British Empire in 1956: the moment when the imperial lion is exposed as a paper tiger…

I, for one, struggle to see the Biden administration responding to a Chinese attack on Taiwan with the combination of military force and financial sanctions…

Yet losing — or not even fighting for — Taiwan would be seen all over Asia as the end of American predominance in the region we now call the “Indo-Pacific.” It would confirm the long-standing hypothesis of China’s return to primacy in Asia after two centuries of eclipse and “humiliation.” It would mean a breach of the “first island chain” that Chinese strategists believe encircles them, as well as handing Beijing control of the microchip Mecca that is TSMC (remember, semiconductors, not data, are the new oil). It would surely cause a run on the dollar and U.S. Treasuries. It would be the American Suez.

Conclusion

Could Taiwan be America’s comeuppance in Asia? In the current era of ascendant China and descendant US, it is the most likely candidate for a conflict the US military appears destined to lose. (Russia is too weak to be much of a threat; an incursion into Ukraine would likely be repelled by NATO)

It may not happen as expected. Rather than an amphibious assault, a Chinese move on Taiwan could instead take the form of an occupation of the other two islands Taiwan seized from China — Quemoy and Matsu. Beijing could take the islands then force Taipei and Washington into a discussion over what happens next.

The big question is, would the US retaliate? I agree with Ferguson that it’s unlikely. China has gone to great lengths to fortify the Chinese mainland against a foreign attack. Their military has been sowing deep-sea mines that sit on the bottom of the ocean and wait for an activation signal. There are likely thousands of these mines covering the South China Sea, and in all likelihood they have set mines along the routes that American carriers would sail, en route to Taiwan’s defence.

China has planted missiles to defend its territory, which extend out to a range of about 1,200 km. They also have submarines outside the South China Sea with the capability of firing long-range missiles. If it came to a war with China, the US carrier fleet likely would not get anywhere near the Chinese mainland to launch any aircraft.

“Since 2017, the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, the service responsible for China’s conventional and nuclear missiles, has added 10 brigades — more than a one-third increase — and deployed an array of formidable new weapons. These new systems include the intermediate-range DF-26 ballistic missile, DF-31AG and DF-41 intercontinental ballistic missiles, CJ-100 cruise missile, and DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle.” What Do We Know About China’s Newest Missiles?

Failing a military response, the most likely action is sanctions, but the US would probably find itself all alone. I wouldn’t expect the European Union to take part, given how important China now is as a trading partner.

Fifty years ago, Henry Kissinger, the US secretary of state under President Nixon, few to Beijing to meet with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai.

In Niall Ferguson’s article he references the parable of the fox and the hedgehog. In an essay by philosopher Isaiah Berlin, an ancient Greek poet wrote, “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

America, writes Ferguson, is a diplomatic fox while Beijing is a hedgehog fixated on the big idea of reuniting China with Taiwan. Kissinger had multiple objectives, including extricating the United States from Vietnam and securing an invitation for Nixon to visit China the following year. Zhou Enlai had one:

“If this crucial question is not solved,” he told Kissinger, “then the whole question [of U.S.-China relations] will be difficult to resolve.”

Fifty years later, nothing has changed. Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party continue to stress that Taiwan is their priority. The fact that the US does not recognize Taiwan yet at the same time underwrites its security and de-facto autonomy, states Ferguson, remains intolerable to China.

Remember, Chinese leaders see their country as a lost empire that needs to be regained, respected, both loved and feared. They want China to assume its rightful place in the world, reunited with territories like Hong Kong and Taiwan that were, in their minds, unfairly stripped from them by imperialist dogs.

China will never give up on Taiwan. Does the United States have the capability to project military power from 8,000 miles away, to an area that is controlled and heavily fortified by its enemy? Does it have the budget and the political will to defend, and suffer massive casualties, an island the size of Maryland? The US may talk a good game with respect to Taiwan, but when the chips are down, my money is on a cut and run, an American Suez.

(By Richard Mills)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments