A year of walking on the wild side for industrial metals

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

The London Metal Exchange’s (LME) tin contract rarely makes the headlines but in February it went into spectacular melt-up.

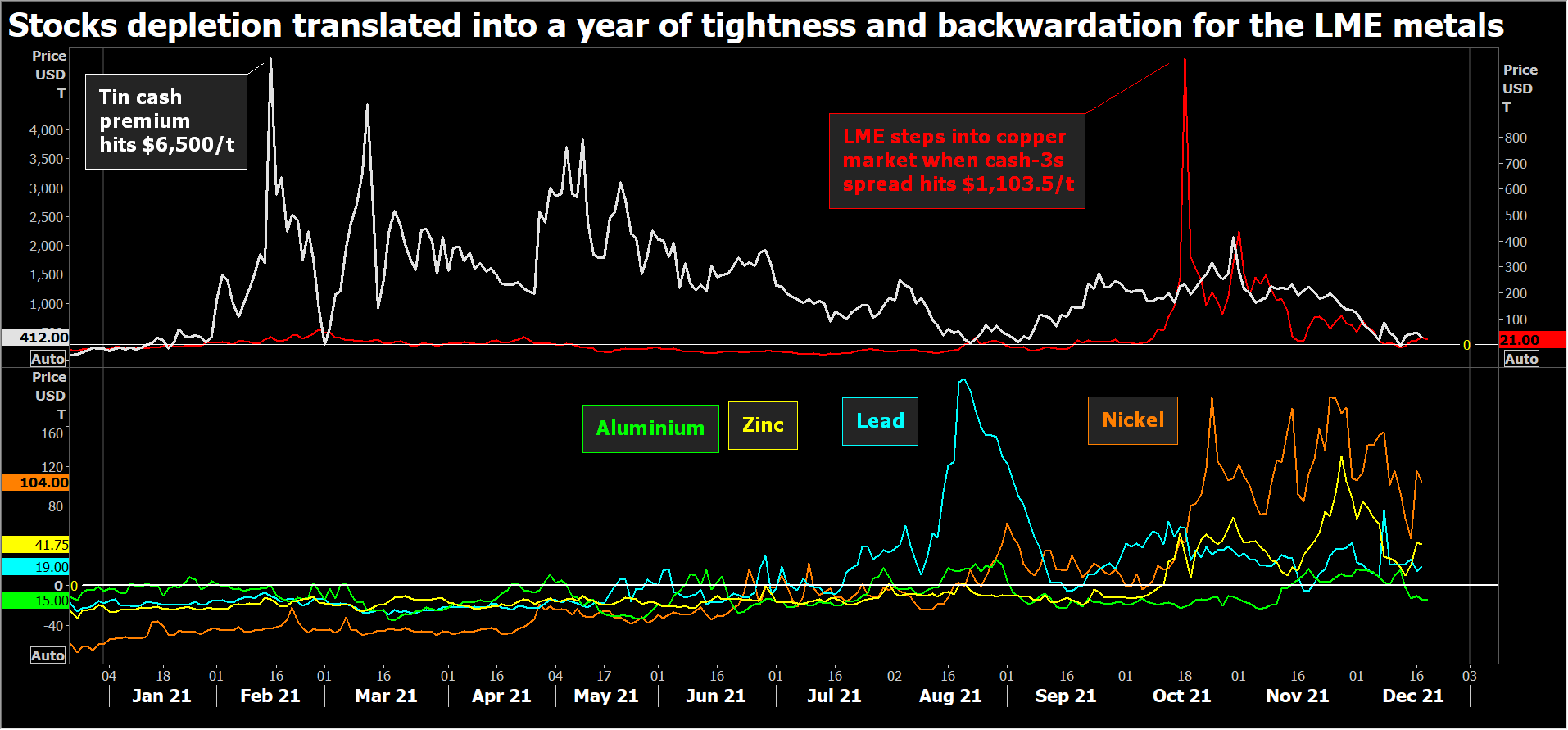

Time-spreads flexed out to surreal levels as exchange inventory fell to historical lows. The premium for cash over three-month metal touched $6,500 per tonne at one stage, eclipsing anything seen before, even during the infamous market squeeze of 2009-2010.

Lead was next.

Spreads blew out in August, the cash premium hitting $208 per tonne, the tightest the London market’s been since 1990.

By October even Doctor Copper turned disorderly. The LME had to step in with the restraints after the cash premium spiralled out of control to an unprecedented $1,103.50 per tonne and the exchange’s monthly prompt date descended into chaos.

Turbulence is in the very nature of commodities markets, not least industrial metals, but this has been a year like no other. Will next year be any different?

The market of last resort

As of the start of December all six of the LME’s primary base metals contracts were trading in backwardation.

The common theme has been one of dwindling stocks.

The total amount of metal held in the LME’s global warehouse system was 2.16 million tonnes at the end of January. By the end of November that had fallen to 1.31 million tonnes.

There has been a partial rebuild over the course of December to a current 1.44 million tonnes thanks to inflows of aluminum and zinc in particular.

Appearances may be deceptive, though, if this month’s “arrivals” are simply metal rotating between LME on-warrant and shadow stocks.

It’s in the LME shadows that the real stocks story has unfolded.

Off-warrant stocks slumped from 2.09 million tonnes in February to 555,000 tonnes at the end of October, according to the most recent figures.

Total LME stocks, both on- and off-warrant, fell by 1.81 million tonnes, or 46%, over the first 10 months of 2021, shadow stocks taking the biggest hit.

This has left accessible stocks highly sensitive to demand for physical metal, such as the raid on copper stocks which left them at a depleted 14,150 tonnes in the run-up to the October mayhem.

The LME has fulfilled its market-of-last-resort function this year with inventory being tapped to fill supply-chain gaps.

Tightness on the LME market has been directly linked to tightness in the real-world physical market-place, where consumers have paid record-high premiums over and above often record-high LME prices to get their metal.

Demand rebound

The industrial metal markets have been collectively caught out by the strength of demand this year.

Tiny tin provided the first clues that the economic rebound from the covid-19 lows of early 2020 was going to be goods-intensive.

Demand for electronic equipment exploded during lock-down, meaning a similar-sized booster for the metal that is used to solder circuit-boards. Global tin usage fell by 1.3% last year but is expected to expand by 7.2% this year, according to the International Tin Association.

Nickel, which is now also experiencing falling LME stocks and tighter time-spreads, has left even tin behind. Global usage was up by an eye-watering 18% in the first 10 months of this year, according to the International Nickel Study Group.

Manufacturing recovery has spread from China to the rest of the world over the course of the year with demand for industrial metals, not just LME metals, booming.

The only brake has been the automotive sector, where output has been slowed by semiconductor shortages, although that only defers pent-up metals demand into next year.

Snapped supply chains

Metals supply chains have been unable to meet this demand.

The first problem has been logistics. The coronavirus disrupted the global shipping sector, leaving in its wake log-jammed ports and sky-high prices, particularly for containers used to transport refined metals.

The LME lead contract was gripped by a rolling squeeze over the middle of the year as stocks were steadily stripped from exchange sheds.

A mountain of lead was sitting in Shanghai at the same time but any arbitrage was inhibited by a lack of shipping capacity. China started exporting significant amounts of lead only in September.

October’s lead exports included 16,475 tonnes to the United States, an extremely rare phenomenon.

But US metal buyers have been particularly hard hit by freight disruption with available supplies of metals such as tin and lead all but exhausted.

Production disruption

Secondly, it has been a year of production disruption, much of it coming from an unexpected source.

Production disruption is normally viewed through the prism of what happens at the mine stage of the value-chain.

But this year the real damage to metals supply chains has taken place at the smelting stage.

Metals smelters are power hungry, which is becoming a big problem in a world that is trying to pivot away from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

The tensions have been starkest in China, where the giant aluminum sector has been hit by mandatory production curbs as provinces try and hit their energy efficiency targets.

But those stresses have more recently spread to Europe, where zinc smelters are now closing due to soaring spot energy prices.

Smelting and refining has emerged as a new and volatile influence on metals pricing.

A wild 2022?

This year started off with Goldman Sachs proclaiming the dawn of a new commodities super-cycle, one driven by a combination of a redistributive recovery from covid-19 and the transition to green technology.

All of the metals have hit multi-year highs in 2021 and the LME Index has notched up year-to-date gains of almost 25%. But there has been a retreat into year-end, reflecting concerns pricing hasn’t escaped the gravitational pull of China, where property-sector concerns loom large.

Only tin ticks all the supercycle boxes. Three-month metal has held steady, currently trading at $38,400 per tonne, just off November’s latest all-time high of $40,680.

Tin stocks are still low, demand is still structurally strong and tin producers are still struggling to match it.

All of which suggests another wild year for the tin market.

But with stocks now low across the board, global logistics still struggling to normalise and smelter-power woes accumulating, the chances of the rest of the metals having a calmer 2022 look slim.

(Editing by David Evans)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments