A vicious cycle of rising resource nationalism

Global warming has raised the economic status and political importance of critical minerals, but with that also comes an increased risk of resource nationalism across the globe.

Resource nationalism risks

The term “resource nationalism” is loosely defined as the tendency of people and governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territory. It is often described as a backward form of state protectionism.

While it presents opportunities for those in less developed countries to seek profit from their natural resources, state ownership can almost certainly exacerbate the instability of the world’s critical minerals supply.

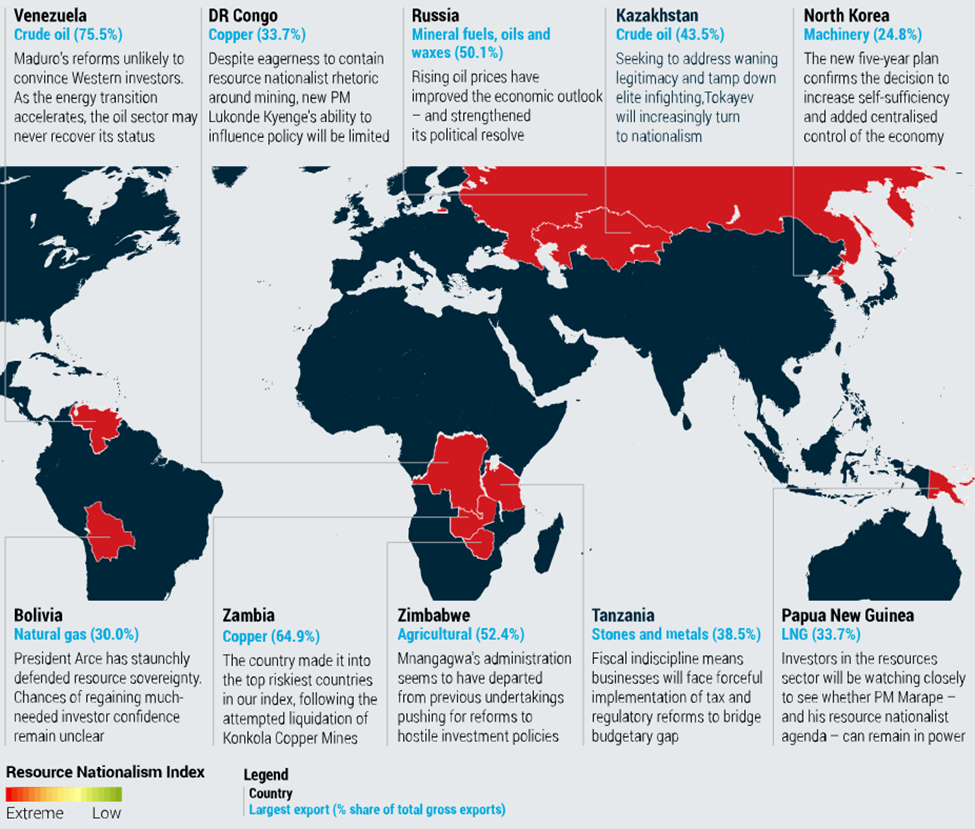

A 2021 report by global risk intelligence company Maplecroft identified an increasing risk of resource nationalism in as many as 34 countries around the world. Dominating the list are Latin American and African countries with large reserves of critical minerals including copper (Zambia), cobalt (DRC) and lithium (Bolivia).

Countries most at risk are those dependent on the minerals they export but have suffered significant economic contractions. These places are more likely to try and recoup their financial losses by targeting the mining industry in their countries, it said.

According to the UK-based firm, resource nationalism can manifest itself in a number of different actions taken by governments, in order of increasing severity:

- Observing existing contracts but not renewing contracts that have expired;

- Indirect expropriation, where an investor retains legal title to their property but is deprived of its economic use (eg, ex post amendment of agreed fiscal terms (tax and royalty rates) to increased governmental share of revenues);

- Lawful nationalization, normally undertaken for public purpose and on a non-discriminatory basis, with due process and fair compensation; and

- Unlawful expropriation of foreign-owned assets without fair compensation.

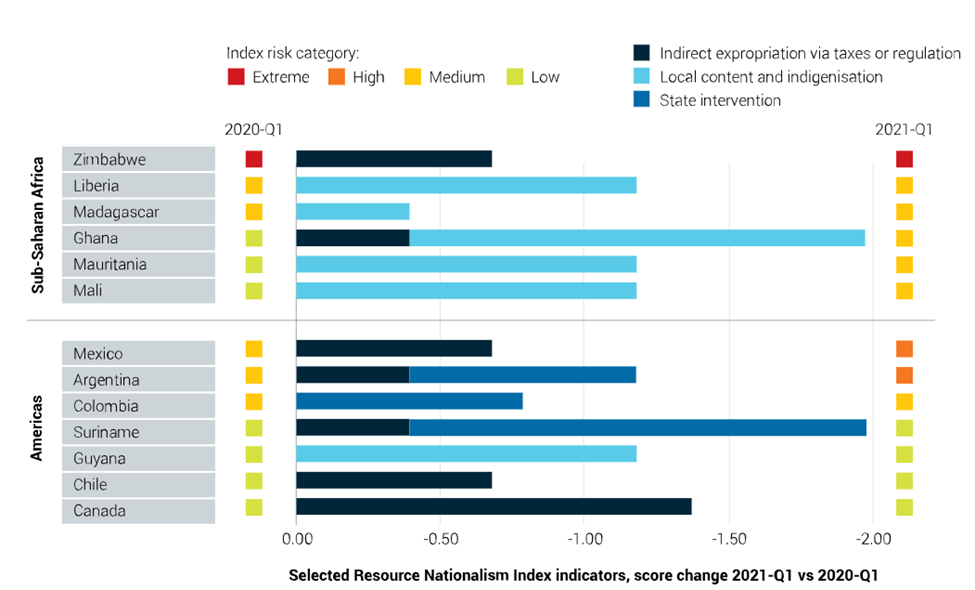

In its report, Maplecroft observed an increasing willingness of governments to intervene in the economy through more subtle means, such as indirect expropriation or demand increases in local content requirements, rather than outright nationalization or large tax increases imposed on foreign mining. In Africa, for example, Mozambique, Zambia and Ghana have all enacted mining laws in the past few years amending their fiscal legislation.

In Latin America, the firm points to two influences behind resource nationalism. The first is ideologically driven, such as Argentina’s nationalization of Repsol’s interest in YPF; and the second is increased pressure from communities to exert greater control over their mineral resources. The latter is best personified by Chile. Triggered by the worst social unrest in a generation, anchored in rampant inequality, the country reportedly has just elected an assembly that will place responsibility for writing a new constitution in the hands of the left wing.

The reforms could give more power to indigenous communities and expand water rights, including a potential ban on mining in areas where there are glaciers, along with increased state ownership of water desalinated by mining companies.

Zambia made it into Maplecroft’s top 10 high-risk list due to an attempted liquidation of Konkola Copper Mines, whereas in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Congolese government in 2018 raised taxes on mining firms and increased royalties. The country is Africa’s biggest producer of copper and cobalt.

One explanation of why resource nationalism has picked up in recent years has to do with globalization. During the 1970s and ‘80s it was common to see developing world governments nationalizing industries. However when globalization emerged in the 1990s, there was a need for foreign investment as governments privatized industries, resulting in fewer attempts to seize foreign-owned assets like mines and factories.

This changed when governments in Latin America, primarily, saw mining profits moving out of the country and they sought to seize greater control over their mineral wealth.

Recent example: Chile’s lithium

Chile is perhaps the most significant example of a “resource nationalism” bombshell that was dropped in recent times.

In April 2023, newly elected President Gabriel Boric announced his plan to nationalize the country’s lithium industry, with the state taking a majority stake in all new contracts. According to the media, state-owned copper mining company Codelco will initially sign up partners for new contracts, after which a national lithium company will have that responsibility.

As well, Codelco and another state-owned miner, Enami, will be given exploration and extraction contracts in areas where there are now private projects. The two lithium miners already in Chile, SQM and US-based Albemarle, will continue to operate until their contracts expire.

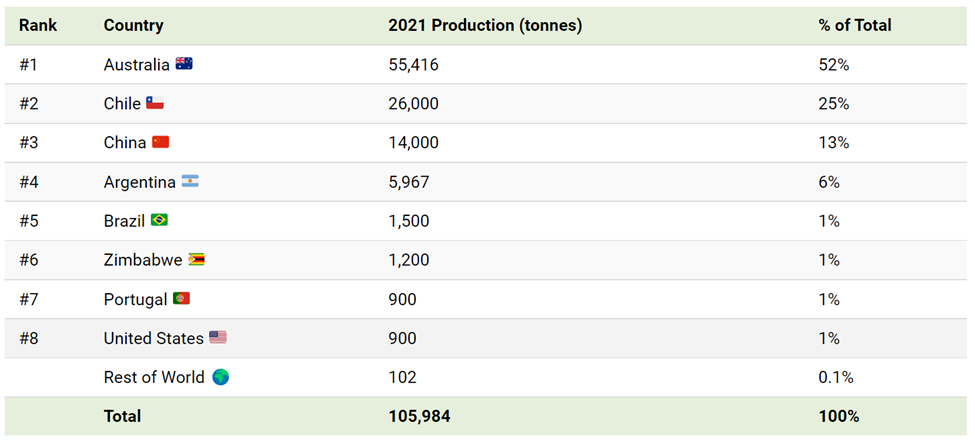

Additionally, the Chilean government wants to create a regional lithium association with neighboring Argentina and Bolivia, which together make up the “lithium triangle” region where 65% of the world’s known lithium reserves are located.

“In Chile, it’s probably going to be the most significant case,” said Carlos Pascual, top energy executive with IHS Markit, via Reuters, referring to the regional efforts to exert more government control over the mineral seen as key to a greener future and Chile’s outsized role in the metals market.

The Latin American nation is currently the world’s 2nd largest lithium producer, representing about a quarter of the global output.

“This is seen as an opportunity to ensure direct revenues to the state just as many countries decided to nationalize oil in a different era,” he added.

Chile’s lithium nationalization comes on the heels of a similar plan announced by Mexico, which has yet to even produce the metal but boasts a respectable quantity of lithium reserves (top 10 in the world).

In early 2022, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez, like his fellow leftist in Chile, enacted a sweeping lithium nationalization and later ordered the creation of a new state-run lithium company called LitioMx.

Lopez Obrador, who reveres the country’s landmark 1938 oil nationalization, justified his policy as its logical extension, arguing that only the government can prevent exploitation by corporations and ensure broadly distributed benefits.

Lithium is certainly not the only mineral targeted by states. Last year, Indonesia announced an export ban on bauxite, the ore used to make aluminum, that would commence June 2023. The aim is to replicate the success of its 2020 ban on raw nickel exports.

Zimbabwe, which already banned exports of raw lithium ore in December 2022, followed that up with an export ban covering all base mineral ores earlier this year.

Key factor: high demand & prices

This trend of increased resource nationalization will likely continue as the global competition for critical minerals intensifies, driving their prices (and potential profits) higher. In Maplecroft’s 2021 study, it mentioned commodity price cycles as an important factor in setting this trend.

In GTDT Practice Guide: Mining 2022, Juliette Fortin, senior managing director of FTI Consulting and a global thought leader, wrote that “the tendency for resource nationalism increases when government bargaining power is higher, which typically occurs at time of increased prices, especially if this coincides with an investor being in a position where they have made sunk investments.”

“There is some debate as to whether the recent increases in mineral prices are the beginning of a new super cycle. However, given the long lead times in mining projects, the rise in demand for critical minerals created by the energy transition will almost certainly lead to an imbalance in supply and demand, which has already precipitated a rise in resource nationalism,” she added.

Also sharing this view is Eurasian Resources Group CEO Benedikt Sobotka. “Resource nationalism typically arises when prices are surging or are expected to do so, and we are seeing an emerging wave of resource nationalism in 2023, including export bans,” he stated in an interview with S&P Global.

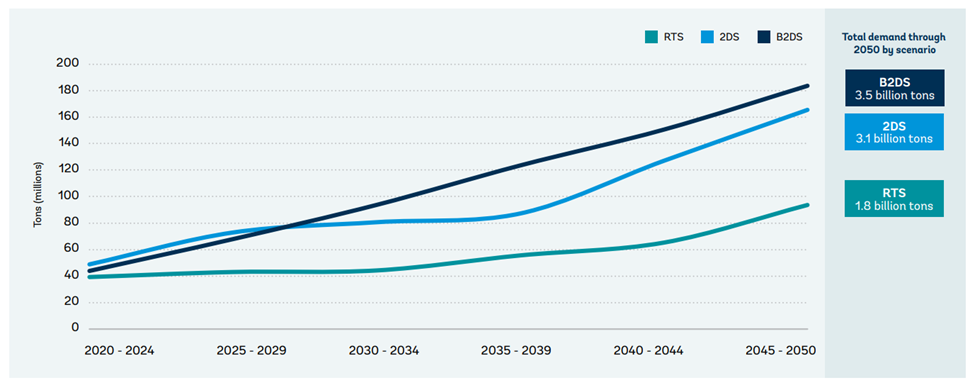

Intensified efforts to build new infrastructure amid the global energy transition could only create a bigger demand for critical battery minerals like lithium, nickel, graphite and cobalt — and, by extension, heighten the resource nationalism risks.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts demand for minerals used in EVs and battery storage will grow at least 30 times by 2040.

Lithium should see the fastest growth, the agency said, with demand growing by over 40x in its Sustainable Development Scenario by 2040, followed by graphite, cobalt and nickel (around 20-25 times). The expansion of electricity networks means that copper demand more than doubles over the same period.

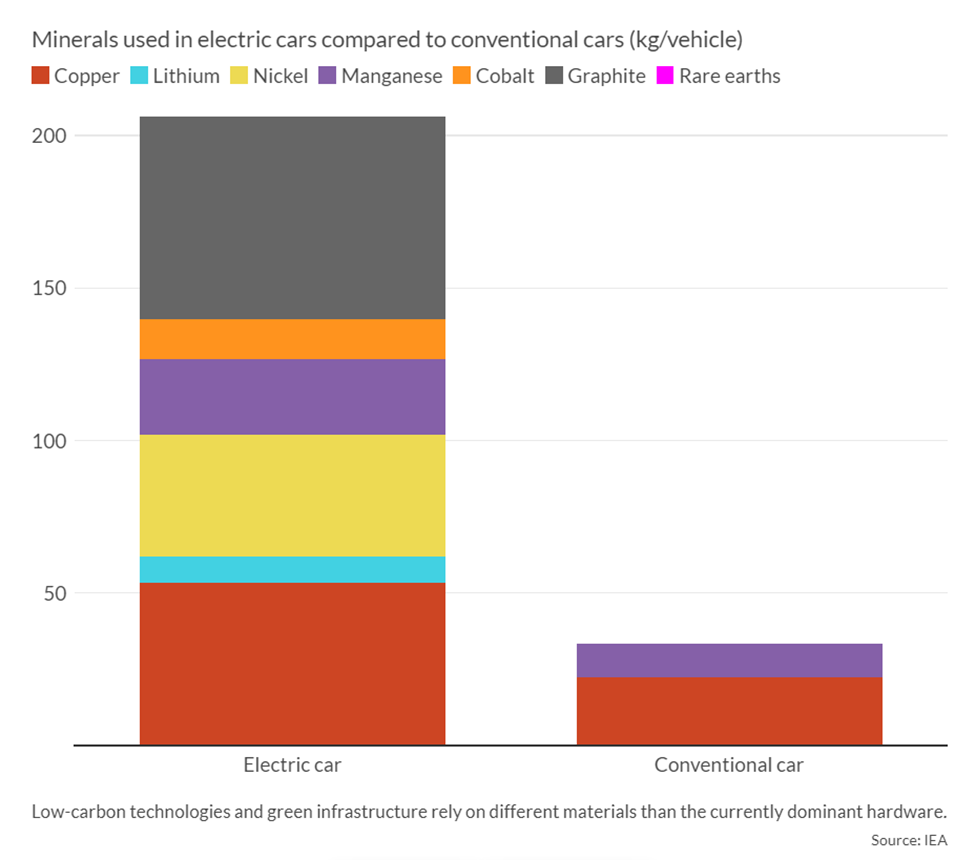

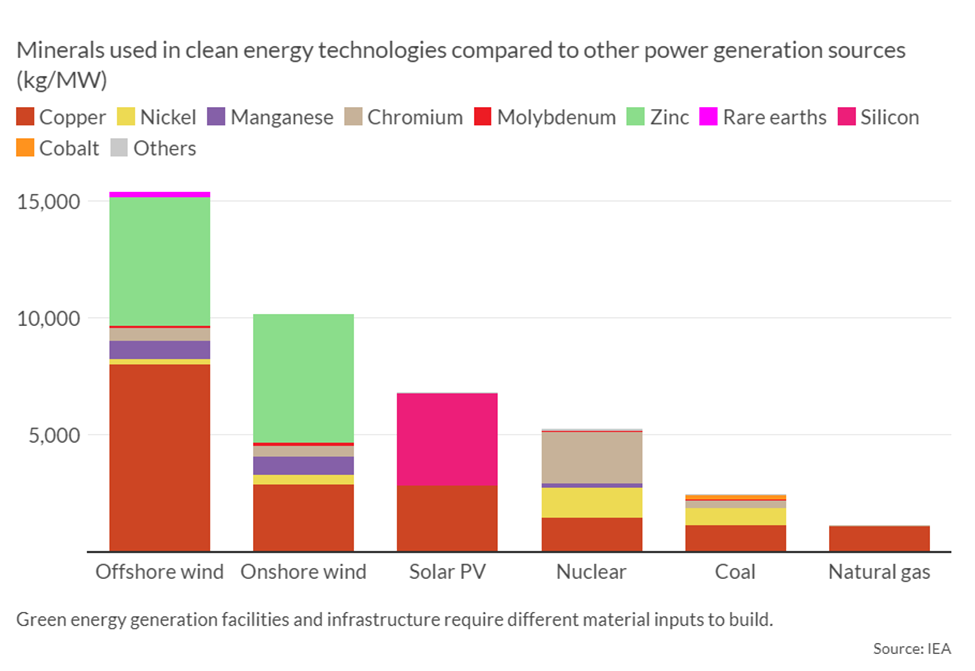

The IEA says solar plants, wind farms and electric vehicles generally require more minerals to build than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. A typical electric car requires 6x the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires 9x more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant.

To meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, IEA data previously showed that sectors contributing to the green energy transition will be responsible for over 45% of the total copper demand, 61% of the nickel demand, 69% of the cobalt demand, and a whopping 92% of lithium demand by 2040.

To reach net-zero, demand for these key metals needed for the deployment of energy transition technologies such as solar, wind, batteries and electric vehicles will grow fivefold by 2050, BloombergNEF research finds.

Lurking threat: supply insecurity

Going hand-in-hand with an increased demand for critical minerals is the security of supply, which can be seen as another contributing factor to resource nationalism.

Admittedly, keeping up with the unprecedented level of demand for these raw materials presents a huge obstacle the world has to overcome. The problem is twofold, one of which is simply down to a lack of supply in the production pipelines.

A 2020 World Bank report estimates that global production of graphite, lithium and cobalt production will need to rise more than 450% by 2050 from 2018 levels, just to meet demand from energy storage technologies.

By 2030, at least 300 new mines – for materials like cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, nickel, rare earth elements (RREs) and vanadium – will need to be brought onstream. That’s no easy task, especially given the time lag between committing the capital, developing the mine and starting production, which can easily span 10 to 20 years.

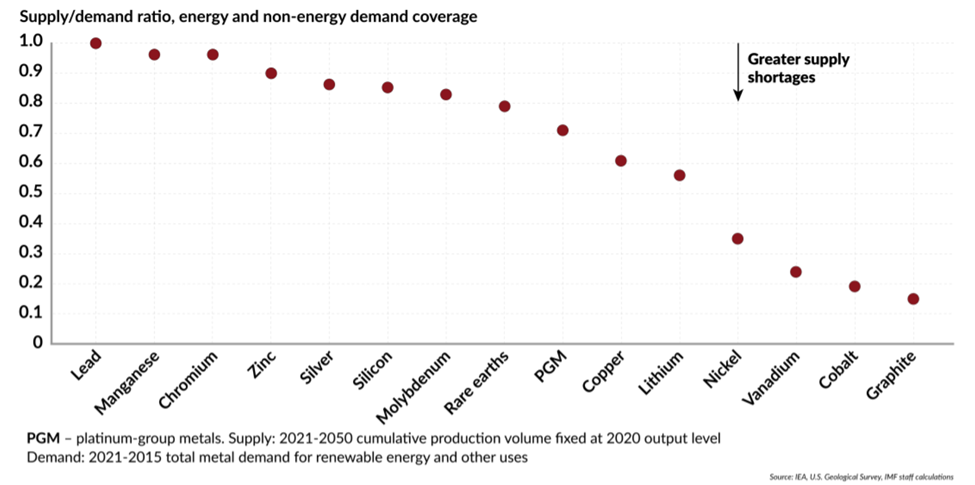

Given the massive projected increase in metals consumption through 2050 under a net-zero scenario, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) fears that current production growth rates are inadequate, and could result in a more than two-thirds gap versus demand. The shortfall in copper, lithium and platinum is expected to vary between 30-40% relative to demand.

Because of the shortfall, “prices could reach historical peaks for an unprecedented length of time,” the fund warned. While this should spur more investment into the mining sector, as mentioned earlier, the threat of resource nationalism also becomes elevated.

According to Dr. Carole Nakhle, an energy economist and CEO of London-based advisory firm Crystol Energy, most studies on the outlook for minerals typically assume that the status quo in the industry’s structure will remain in place and the risk of significant disruptions to that structure has been largely overlooked.

“When a natural resource gains greater strategic importance and its value increases accordingly, it attracts state intervention and control,” she wrote in a May 2023 article on how resource nationalism could further complicate the energy transition.

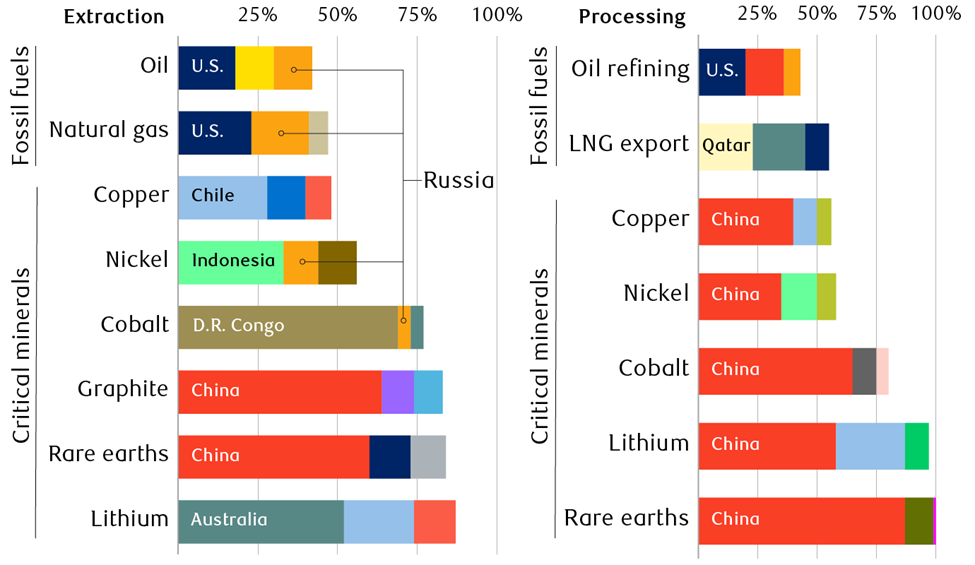

This brings us to the second main issue with supply security — that the key mineral deposits tend to be concentrated in the hands of a few countries which can have outsized influence on supply chains. In fact, the production of many minerals is more geographically concentrated than that of oil or natural gas.

Critical mineral processing is even more concentrated, with China the dominant player, as depicted in the graphic below.

Such high concentrations, as you can imagine, make any supply chain susceptible to disruption. In extreme cases, it could lead to a “weaponization” of critical minerals, the most recent example being China’s export curb on gallium and germanium.

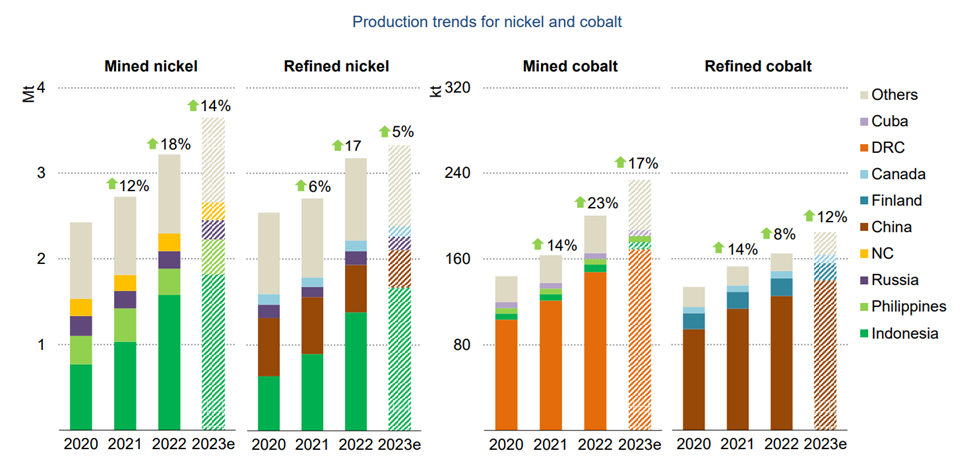

A recent study by IEA found that the concentration of supply is actually intensifying for some critical minerals in 2022 despite US and Europe’s efforts to diversify and reduce reliance on China.

The minerals in question include nickel and cobalt, both key ingredients in EV batteries whose supply sources are heavily concentrated. Nearly 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, while about a third of nickel production is credited to Indonesia.

The IEA report also confirms that China controls a majority of the metals processing business, establishing itself as the dominant force in the battery metals supply chain.

“Our analysis of project pipelines reveals a somewhat improved outlook for mining, but not for refining operations where today’s geographical concentration is greater,” the agency stated.

Planned projects are mostly developed in incumbent regions, with China holding half of planned lithium chemical facilities and Indonesia representing nearly 90% of planned refined nickel plants, the IEA said.

“Many resource-holding nations are seeking positions further up the value chain while many consuming countries want to diversify their source of refined metal supplies. However, the world has not yet successfully connected the dots to build diversified midstream supply chains,” it added.

Supply dominance & resource nationalism

Without a more diversified supply chain, resource dependency would continue to be a main theme of discussion and a threat to the main importers of critical minerals.

Prior to releasing its 2023 Critical Minerals Market Review, the IEA had already warned that high concentration levels increase the risks that could arise from physical disruption, trade restrictions or other developments in major producing countries.

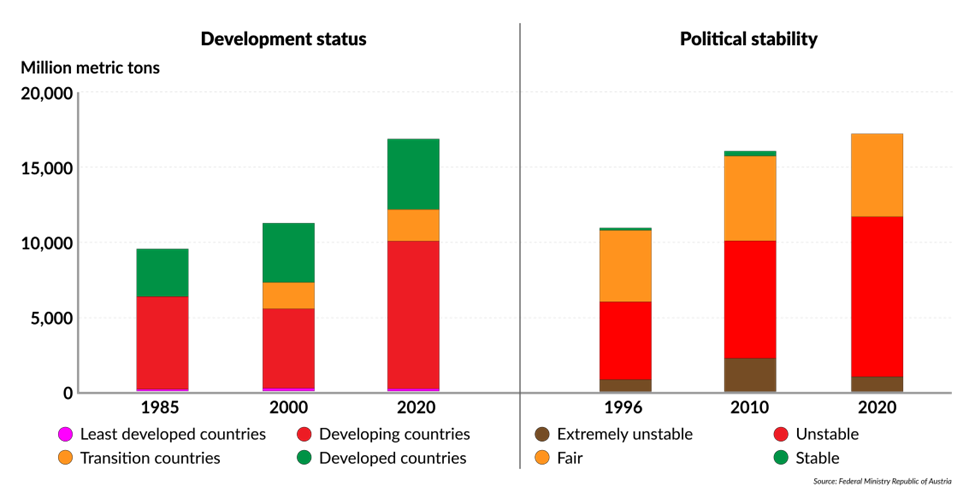

According to the Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Regions and Tourism, most of these producing countries are politically unstable, and so the risk and cost of doing business there are greater.

Furthermore, the governance of natural resources in many of these places is “suboptimal,” as the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) put it.

Additionally, for all those countries, the mining sector has strategic importance, especially where it is the backbone of the economy and the primary source of government revenue. Countries are considered resource-dependent when metals and minerals account for more than 20% of exports by value, and mineral rents are more than 10% of the country’s GDP, according to the ICMM. In many countries, that threshold is easily exceeded.

To paraphrase Dr. Nakhle’s article:

“All the above factors – from the concentration of production and reserves to the sector’s strategic importance and particularly the potential for high prices – create fertile ground for a rise in resource nationalism.”

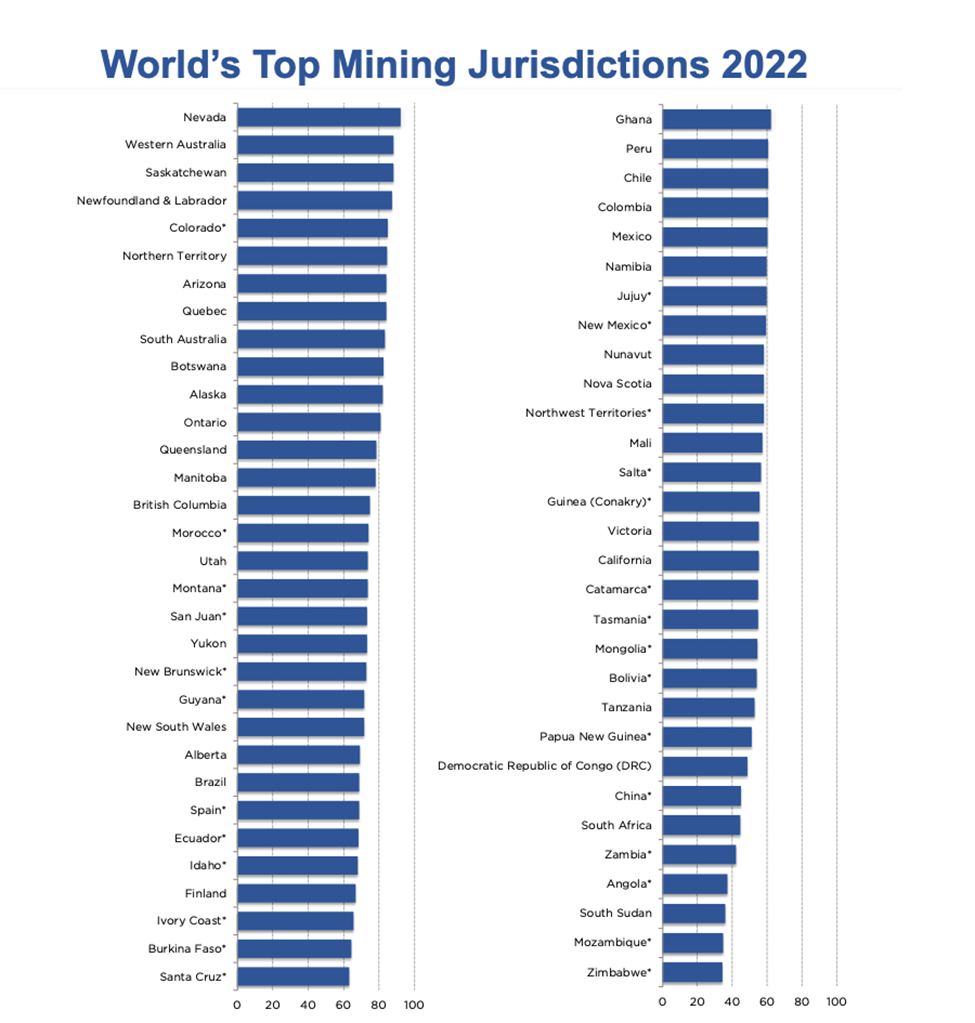

This explains why many of the countries with high scores on Maplecroft’s Resource Nationalism Index also happen to be those with the richest mineral reserves. By cross-referencing nations with the largest reserve base for certain minerals (based on USGS figures) with those that have high potential for resource nationalism, we see a clear overlap (in asterisk below).

According to the GTDT Practice Guide, an increase in resource nationalism will create a conflict between the interest of states to maximize the value of their natural resources and the interests of producers to maximize production in response to the demand created by the energy transition.

This is reflected in the rising number of international arbitration claims brought by investors against national governments. For example, Colombia is currently facing an ICSID claim over attempts by the state’s authorities to retroactively claim more than US$180 million in royalties. Peru is also facing a pair of claims from investors in the Carro Verde copper-molybdenum mining project relating to a demand for US$316 million in royalties.

Given the abundance of critical minerals in countries with a track record of resource nationalism, it’s expected that dispute activity will continue to increase in the future. A rise in disputes would therefore reduce the incentives for investors to invest in these jurisdictions, placing pressure on an already strained global supply.

Over time, this dynamic would create a “vicious cycle” of heightened resource nationalism risk motivated by an increasing strategic and economic importance of minerals, thus severely delaying the global energy transition.

Mining-friendly jurisdictions

Of course, the far easier way to lessen the risk of resource nationalism is to steer clear of countries that are considered high investment risks and shift toward those with sufficient resources and policies designed to maximize mining operations.

For many years the mining industry has been guided by the Fraser Institute’s annual investment attractiveness index, which rates regions based on their geologic attractiveness and the respective government policies and attitudes toward mineral exploration. The index is constructed from the responses given by select industry participants who have been asked to rank provinces, states and countries according to various public policy factors in an annual survey.

The 2022 edition of Fraser Institute’s survey revealed Nevada as the top jurisdiction in terms of investment attractiveness, moving up from 3rd place previously. Western Australia, which topped the 2021 list, ranked 2nd this time. Saskatchewan continues to be on the podium, dropping slightly from 2nd to 3rd (see below).

Rounding out the top 10 are Newfoundland & Labrador, Colorado, Northern Territory, Arizona, Quebec, South Australia, and Botswana. The US, Canada and Australia each have three jurisdictions in the top 10 list, followed by Africa with one.

Meanwhile, Zimbabwe is ranked as the least attractive jurisdiction for investment followed by Mozambique, South Sudan, and Angola. Also in the bottom 10 (beginning with the least attractive for investment) are Zambia, South Africa, China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Papua New Guinea and Tanzania. Africa is the region with the most jurisdictions (8) in the bottom 10. Asia and Oceania each have one jurisdiction in the bottom 10.

Conclusion

At AOTH, resource nationalism/country risk is always at the top of our considerations when conducting due diligence on exploration companies. As such, it’s no coincidence that all of the resource companies featured on the website appear on the left (low risk) side of the above table.

Many of those are exploration companies that happen to focus on critical minerals, a market that is seeing unprecedented growth as the global energy transition continues to drive up demand.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments