A Tesla co-founder aims to build an entire US battery industry

Redwood Materials Inc., the battery recycling company created by Tesla Inc. co-founder J.B. Straubel, has been keeping a big secret: It isn’t really a recycling company.

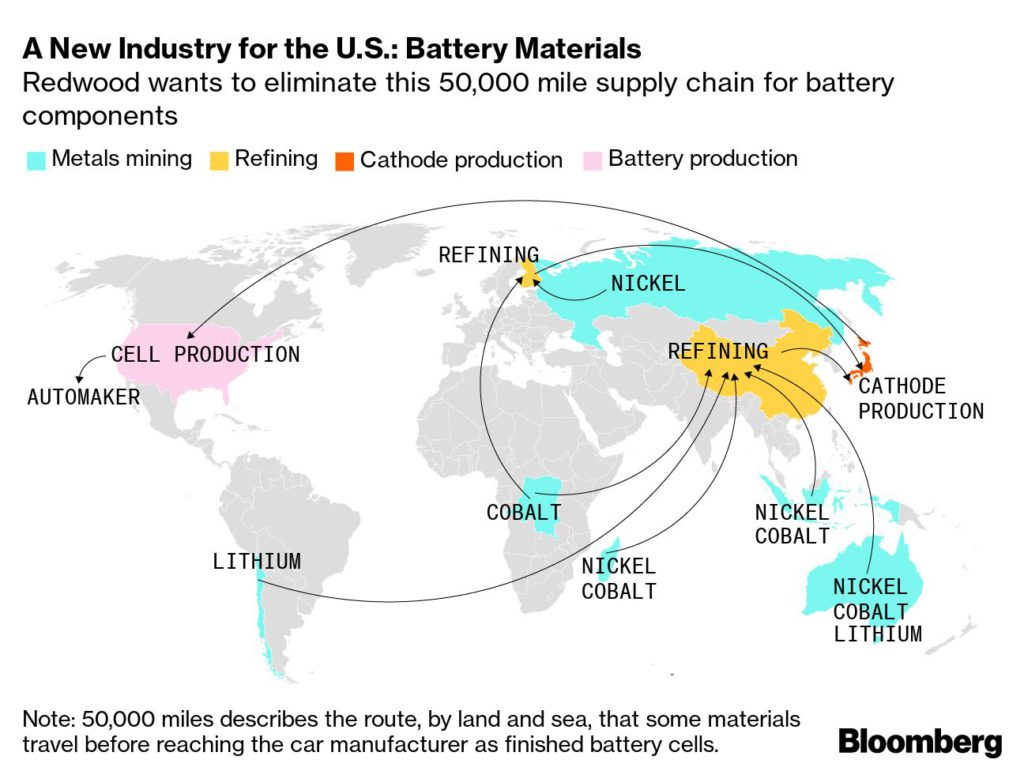

Sure, Redwood has risen quickly to become the biggest lithium-ion battery recycler in the U.S.. But Straubel didn’t leave Tesla in 2019 just to clean out America’s junk drawers. His broader goal, described to Bloomberg for the first time, is to move a huge chunk of the battery-component industry from Asia to the U.S.

“It’s both inspiring and terrifying to see so many nations and car companies announcing their shift to electric vehicles,” Straubel said. “But there’s a massive gap in what needs to happen.”

To fill that gap, Straubel has set out to build one of the largest battery materials factories in the world. Redwood, which currently operates three facilities in Nevada, is searching for a location farther east to build a new million-square-foot factory. At a cost of well over $1 billion, according to Straubel, the addition will enable Redwood to become a major U.S. producer of cathodes. (Every battery has two electrodes — an anode and a cathode — between which trillions of charged lithium atoms travel. It’s the cathode that largely determines a battery’s cost, performance and environmental footprint.)

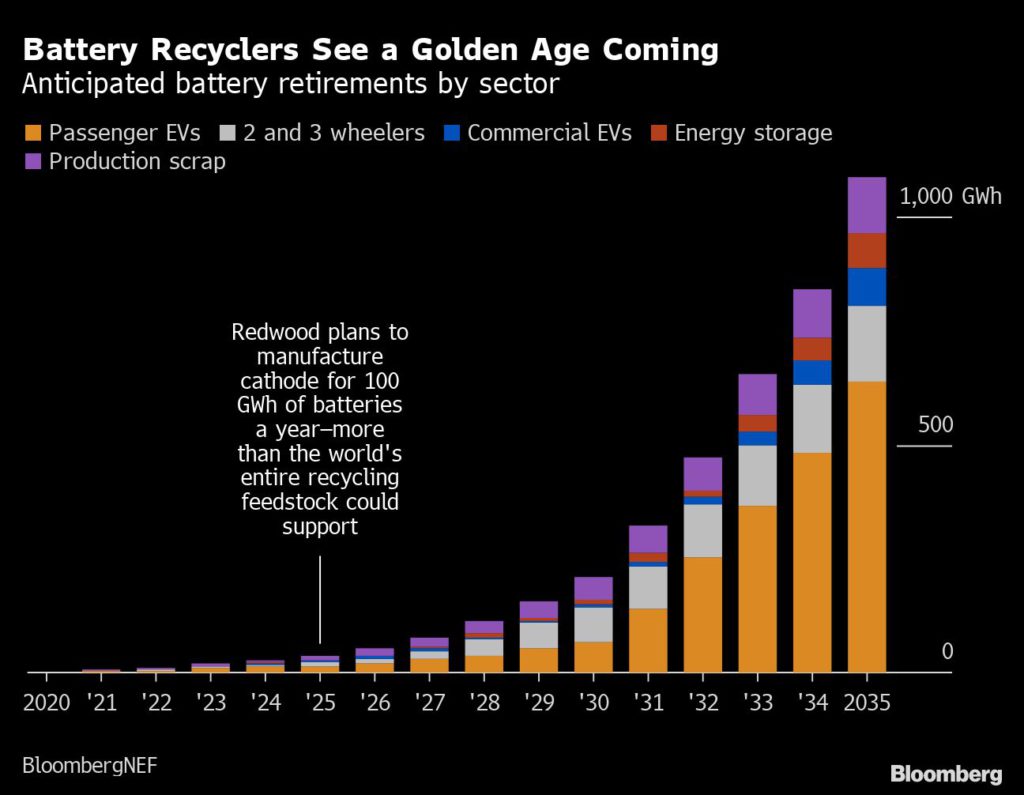

Straubel says the U.S. factory will produce material for 100 gigawatt hours of batteries a year by the end of 2025. That’s enough for about 1.3 million long-range vehicles a year, on par with the biggest producers in Asia. By 2030, the same facility will ramp up to 500 gigawatt hours a year, he says. At today’s prices, that’s $25 billion of cathodes a year. Redwood plans to build a similar operation in Europe by 2023.

“These numbers sound insane, but when you look at what the market needs, I’m like holy cow — is this even aggressive enough?” Straubel says. “Somebody’s got to do this. In fact, we need at least four companies doing similarly aggressive, crazy things all in the same timeline.”

Electric vehicles make up just 4% of passenger vehicle sales today, but the big flip is coming. At least 15 countries and 31 cities have announced timelines to entirely phase out sales of internal combustion vehicles, beginning with Norway in 2025. Last month, U.S. president Joe Biden signed an executive order targeting half of U.S. auto sales to be electric by 2030. General Motors Co., the biggest U.S. automaker, has pledged to electrify all of its vehicles by 2035.

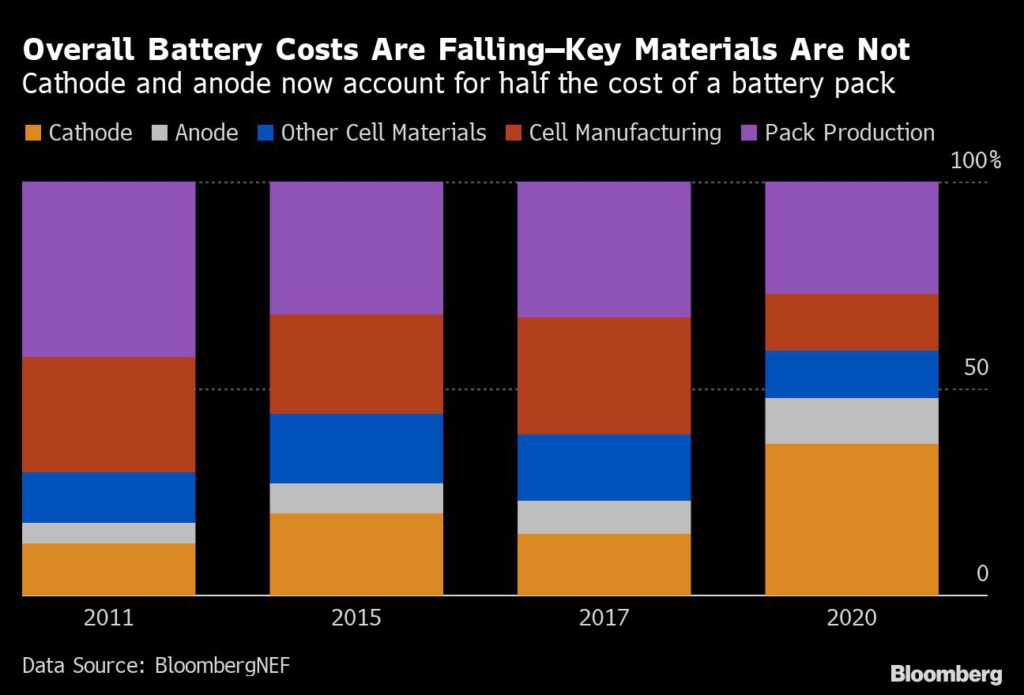

These EV promises are predicated on the economic force of falling battery prices. Every time the global supply of batteries doubles, the price of making them drops about 18 percent, according to data tracked by BloombergNEF. It’s a learning curve driven by large investments in battery manufacturing like Tesla’s battery Gigafactory in Nevada. There’s one glaring exception to this rule: battery materials.

China accounts for more than 80% of global production of battery components and materials, BNEF data show. While planned new battery factories in the U.S. and Europe will help challenge Asia’s dominant role, they’ll remain dependent on the region without huge new investments in basic battery components.

The not-just-recycling company

Straubel left Tesla, in part, because of his growing alarm over a looming choke point in the global supply chain. Car companies were finally paying attention to battery manufacturing, he said, but were less interested in the “less sexy” components that go into them. Redwood is pursuing three types of operation: recycling, manufacturing copper foils for anodes, and producing cathodes. Recycling is done at headquarters in Carson City, Nevada. The company recently broke ground on a 100-acre site in Story County, Nevada, to make the delicate copper foils, a component in short supply. A cathode factory will be its biggest endeavor by far, Straubel says.

The company’s target of 100 GWh in 2025 means it can no longer rely on recycled materials alone. Unlike some consumer electronics, there’s a long lag between when electric cars are made and when their batteries are ready to be recycled. The reuse of packs in secondary applications can delay that further. Today, electric cars account for less than 10% of Redwood’s recycling stock. “We’re going to push the recycled percent as high as possible, but that is really going to be dependent on the availability of recycled materials,” Straubel said. “If we end up consuming 50% or more of virgin raw materials, that’s fine.”

In the decades to come, Straubel is confident that recycled materials will be used for “close to 100%” of the world’s battery production. Recycling is already profitable, he said, and eventually companies that don’t integrate recycling with refining and production won’t be able to compete on cost. Challengers are equally confident in the outlook, including Worcester, Massachusetts-based Battery Resourcers Inc., Canada startup Li-Cycle Holdings Corp. and industry incumbents like China’s GEM Co.

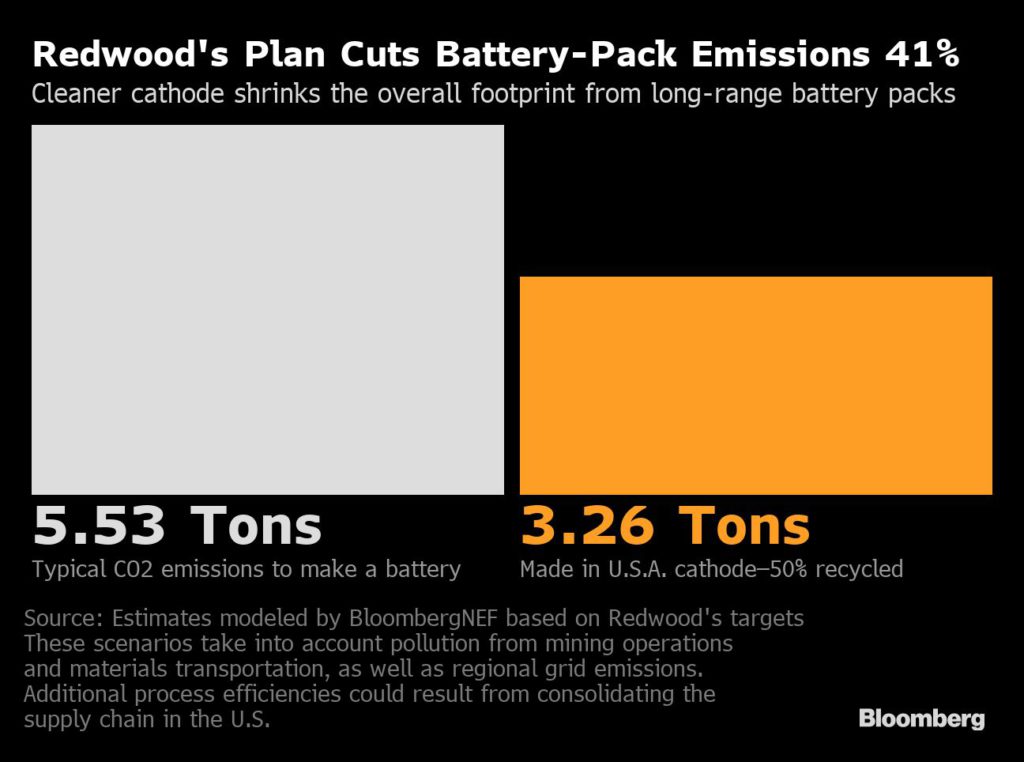

Redwood moving into cathode production is a major development for the EV industry, according to BNEF analyst James Frith. Not only is the cathode the biggest driver of costs, but it’s the most polluting part of battery production. Consolidating the supply chain in the U.S. — and the technological improvements that will come with it — will dramatically reduce emissions from battery production.

“It would be one of the biggest cathode facilities in the world,” Frith said. “If you’re getting rid of that long supply chain, and you’re not having to do as much virgin refining, you’re cutting a huge chunk out of those emissions.”

166 iPhones of cobalt

While companies wait for the first big wave of electric vehicles to reach retirement, consumer electronics provide a surprisingly effective substitute. For example, batteries from consumer electronics contain considerably higher levels of cobalt, one of the most expensive and controversial inputs for batteries. It would take 6,147 recycled iPhone batteries to provide enough lithium for a Tesla Model Y but just 166 iPhones to provide enough cobalt, according to BNEF calculations. Straubel says there’s so much cobalt in old electronics, Redwood will always produce more from recycling than it needs for manufacturing.

Somewhat counterintuitively, building electric cars produces more pollution than building gasoline-powered cars, due to the high energy requirements for battery production. EVs, however, are so much more efficient to operate, they more than make up for this starting deficit over the life of the car—even in places where most electricity comes from coal.

In the U.S., it take about 16,000 miles of driving before an electric vehicle becomes a net positive for the environment — or roughly a year and half of car ownership for the average American driver, according to BloombergNEF. Redwood’s plan would nearly cut that in half, according to Frith. Consolidating the supply chain in the U.S. and using 50% recycled material would cut the emissions from battery-pack manufacturing by at least 41%.

Urban mining

When anyone drops off an old mobile phone or laptop at a Best Buy recycling center, it goes to Redwood. So does any scrap when Panasonic makes battery cells for Tesla at the Nevada Gigafactory. Since Straubel left Tesla, Redwood has taken over more than half of the U.S. market for lithium-ion battery recycling. It struck battery-waste deals with Amazon.com Inc., electric bus maker Proterra Inc., Specialized Bicycle Components Inc. and, importantly, an exclusive deal with the largest electronics consolidator in North America, Electronics Recycling Services (ERI).

After collection, Redwood disassembles, shreds, burns, and mixes materials in a slurry to separate out the valuable nickel, lithium, cobalt and copper. More than 95% of the core battery materials are recycled, according to Redwood. The resulting powders then wind their way back through the supply chain.

Before Redwood, most U.S. recycling shops simply ground up the batteries into a crude powder known as “black mass” for easy transportation, and then shipped those materials overseas to be refined and processed, according to Jeffrey Spangenberger, director of the Department of Energy’s ReCell Center for battery recycling research. That’s better than not recycling at all, but it still takes a heavy environmental toll and doesn’t reduce dependence on foreign suppliers.

More than 95% of the core battery materials are recycled, according to Redwood

“We want to buy these materials once and then keep them here,” Spangenberger said. “The recycler and the manufacturer together — if that can be done under one roof, then we’re answering two questions at once.”

There’s a reason Straubel is being listened to, even when making dramatic forecasts for what is an embryonic industry with a still uncertain growth trajectory. He was the mastermind behind Tesla’s battery strategy from the first time Elon Musk approached him, following an engineering talk at Stanford University in 2003.

When Straubel left Tesla, he brought along Kevin Kassekert, another key confidant of Musk, as chief operating officer of the new company. Kassekert was in charge of building Tesla’s sprawling battery “Gigafactory” in Sparks, Nevada. Kassekert was responsible for finding the site, building the factory, and hiring most of the people who operated it.

Now, he aims to do the same thing for battery materials at Redwood. “In 2013 there wasn’t any major battery manufacturing in the U.S.,” Kassekert said. “Fast forward eight years, and there’s not a lot of battery component manufacturing in the U.S. We’re focused on filling that void.”

Since it’s a new industry for the U.S., Kassekert and Straubel have been piecing together a workforce from around the world. Redwood opened small offices in Norway and Japan. Recent hires include Alan Nelson, a former chief technology officer at Johnson Matthey Plc, the British chemicals company, where he built a cathode business. Koichi Ichinose spent more than three decades at Dow Chemical Co. and at Albemarle Corp., the biggest lithium miner. And David Okawa was a senior director of research and development at SunPower Corp., where he worked for 11 years ramping solar-cell technology.

Redwood has raised roughly $740 million in two investment rounds since 2020. Investors include Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund, and Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. A $700 million capital raise in July valued Redwood at about $3.7 billion.

Straubel declined to disclose the size of his personal stake — he was a major investor in each funding round. “This is fun and rewarding to me, it’s where I want to invest.”

The company’s next steps, he said, will require significantly more money than they’ve raised so far, and options are being explored. But he’s not ready yet for an initial offering of stock.

“It’s not off the table, but we’d prefer to grow the company in other ways for a little bit longer.”

(By Tom Randall, with assistance from Jacqueline Gu)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments